The Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria produced the first anti-smoking television advertisements in Australia in 1971. A series of 26 low-budget black and white advertisements were created, mostly humorous and featuring English actors Warren Mitchell, Fred Parslowe and Miriam Karlin. Also during these early years of tobacco control, Nobel Laureate Sir MacFarlane Burnett appeared in two television advertisements about lung cancer and teenage smoking. 1

Following the initial ‘Quit. For Life’ campaign community trial in the late 1970s as part of the New South Wales North Coast Healthy Lifestyle Program, 2 statewide public education campaigns were developed in Australia by some states in the early 1980s. These commenced in New South Wales, Western Australia, Victoria and South Australia, and were funded by government and non-government organisations. In Queensland, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory, tobacco control activities were initiated by a range of organisations. 3 Since then, campaigns have been developed and implemented nationally (see Section 14.3.2) and across states and territories (see Section 14.3.3) as part of increasingly comprehensive tobacco control programs. Unless otherwise stated, the campaigns described in this section are primarily televised campaigns, often supported by complementary campaign materials developed for other channels such as radio and print.

Table 14.3.1 lists all major television anti-smoking campaigns aired in Australia from 2001 to 2017. The table demonstrates the extent of licensing of campaigns across Australian states and territories, and where campaigns have been adapted from other countries. An overview of the role of social media in public education to discourage smoking is included in Section 14.4.7.3.

14.3.1. Investment in televised tobacco control campaigns

As Section 14.3.2 and 14.3.3 below describe, federal and state-based agencies in Australia have used television campaigns as a key component comprehensive tobacco control programs for almost 50 years. However, investment in televised anti-smoking campaigns has fluctuated over time, often falling well below the best-practice minimum benchmark of 70%-80% of the target audience exposed once and 50%-60% exposed at least 3 times to the main video message per month. For television this equates to at least 400 television audience rating points (TARPs) per month, or 4800 TARPs annually. 4 TARPs are a measure of population reach achieved by a television campaign. One hundred TARPs may be equivalent to 100 people viewing an advertisement once, or 50 people viewing an advertisement twice. Regular exposure above this benchmark is needed to achieve population-level changes in smoking prevalence. 4 Figure 14.3.1 shows the population-weighted annual TARPs for all federal and state-sponsored anti-smoking television campaigns from 2001 to 2017. The minimum benchmark of 4800 annual TARPs was achieved in only 8 of the 17 years examined.

State-sponsored anti-smoking campaigns alone achieved 4800 TARPs annually in 2006 to 2009, then fell to an average of 3600 from 2010 onward (population-weighted). Federal campaigns have fluctuated more widely, ranging from none in 2008 and 2009 to approximately half of all campaigns in 2011. Total advertising levels were highest in 2006-07 and 2011-12 at around 7000 TARPs annually. Average televised anti-smoking TARPs were just over half that for 2014 to 2017. During this latter period, federally sponsored TARPs fell to an average of 540 annually.

Figure 14.3.2 shows federal government expenditure on anti-smoking campaigns from the 2010-11 financial year to 2019-2020, adjusted for inflation to $2018. This expenditure includes all campaigns for which total expenditure exceeded $250,000, including television, radio, print and cinema, among other channels. Australian government expenditure on anti-smoking campaigns was almost $36 million in 2010-11 and $31 million in 2012-13. Expenditure then fell by more than 80% in 2013-14 and has remained at $10 million or less annually to 2017-18. Annual federal expenditure on anti-smoking campaigns in 2017-18 was one-fifth of that in 2010-11.

14.3.2 Programs initiated by the Australian Government

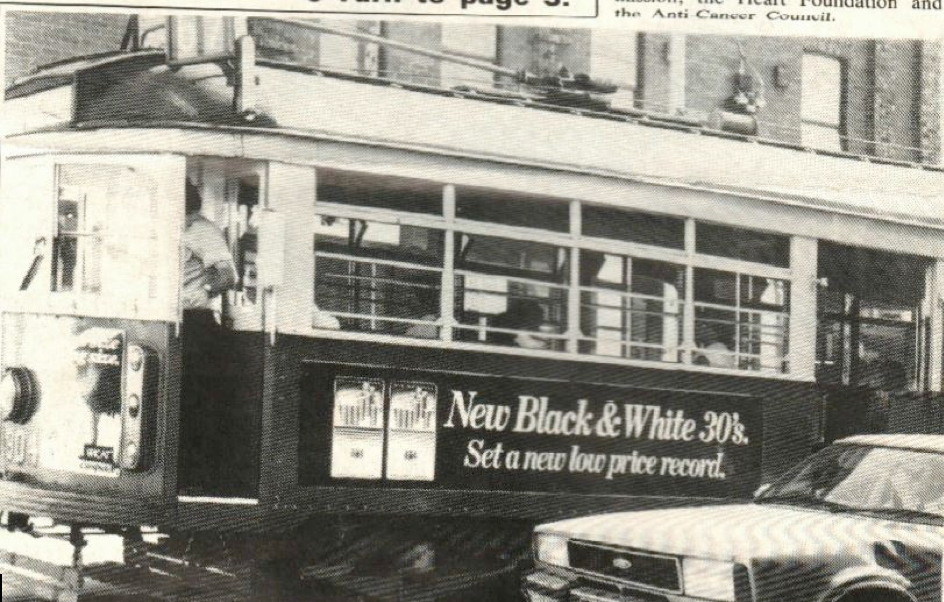

The first national campaign on smoking was the National Warning Against Smoking campaign conducted between 1972 and 1975 at a cost of $0.5 million per annum. 5 The campaign used posters and slogans with anti-smoking messages. Figure 14.3.3 demonstrates how anti-smoking public education campaigns began to displace cigarette advertising.

Source: Cancer Council Victoria Heritage project photo collection.

As part of the campaign, the Commonwealth Department of Health printed cardboard signs requesting smokers not to smoke nearby; these were made freely available to the public. As the campaign was not formally evaluated no information is available about its impact. Sections 14.3.2.1 through 14.3.2.6 describe national campaigns since 1990. A list of all television campaigns aired since 2001 is provided in Table 14.3.1.

14.3.2.1 The National Campaign Against Drug Abuse

The Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy (MCDS) was formed in 1985, comprising all Australian state and territory Health Ministers, Commonwealth Ministers for Health and Customs, and the Attorney-General. 6 An early initiative of the MCDS was the launch of the National Campaign Against Drug Abuse, which aimed to reduce drug use in the community through education, rehabilitation and law enforcement. This program was later renamed the National Drug Strategy. Importantly, the National Campaign Against Drug Abuse acknowledged tobacco smoking as the major contributor to drug-related deaths in Australia. 6 This ensured that tobacco issues maintained a high profile among health professionals and the media.

As part of the social marketing arm of the National Campaign Against Drug Abuse, a $2 million national television, cinema and print advertising campaign asking ‘Smoking – who needs it?’ was launched in 1990 and continued through 1991. It targeted teenage girls and young adult women 7 and was designed to complement existing state-based programs. Campaign evaluation surveys showed significant increases in negative perceptions of smoking among the target audience, and an elevation in the percentage of young girls intending to reduce their rate of smoking. 8 A low-key cinema campaign aimed at teenage smoking was conducted in 1995.

14.3.2.2 The National Tobacco Campaign 1997–2001

Through the 1990s Quit organisations working across Australia cooperated extensively with materials being shared or adapted where possible (personal communication, Quit Victoria Directors Michelle Scollo (1988 to 1994) and Judith Watt (1995 to 1999)). However it was not until 1997 that a truly national campaign, galvanising the collective expertise and resources of all Australian Quit campaigns and the Commonwealth, was launched.

The National Tobacco Campaign was developed as steady reductions in smoking prevalence observed through the 1980s and early 1990s were stalling. 9 In 1995, the Australian Government allocated research funds towards regaining the tobacco control momentum. In 1996, a commitment was made to pool the extensive tobacco control expertise and resources in Australia to develop a collaborative national anti-smoking campaign. 10 Managed by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care with advice from a Ministerial Tobacco Advisory Group chaired by Professor David Hill, the National Tobacco Campaign was launched in June 1997 with funding of over $7 million across two years. The added support from state-based organisations meant the total investment in the first six-month phase of the National Tobacco Campaign was approximately $9 million. 11 With the advent of the National Tobacco Campaign, funding for tobacco control programs in Australia increased from 26 cents per adult in 1996 to 55 cents per adult in 1998 and continued at 49 cents per adult in 2001. 12

The Australian Government contributed 75% of the $4.5 million spent on advertising in the initial phase of campaign activity (June–October 1997). In subsequent phases of the campaign, states and territories contributed more: by 2000 the Australian Government contribution was estimated at $2.18 million compared with $3.29 million from state and territory Quit organisations. 13

The National Tobacco Campaign targeted smokers aged 18–40 years. It was Australia’s most intense and enduring mass media tobacco control campaign. One of its great strengths was the collaboration in its development and operation between the national, state and territory governments and non-government organisations.

The primary objective was to elevate quitting on smokers’ personal agendas. The campaign recognised that to potentiate the intention to quit smoking, an individual needed to gain fresh insights. Smokers needed to see material as personally relevant and gain confidence in their own ability to quit smoking (self-efficacy) as well as see they would gain more than they lost by giving up smoking. The task of the creative strategy was to instil the message and remind smokers of it often so that it remained on their personal agenda. 14

The creative development process called for close collaboration between the advertising agency’s creative team and medical experts in the cardiovascular, neurology and respiratory fields. Between 1997 and 2000, six health effects advertisements were produced (known as ‘Artery’, ‘Lung’, ‘Tumour’, ‘Brain’, ‘Eye’ and ‘Tar’) and one ‘Call for help’ advertisement showing a caller to the Quitline. A key feature of the campaign materials was the tagline ‘Every cigarette is doing you damage’. The scripts and some videos of advertisements can be viewed here: http://webarchive.nla.gov.au/gov/20110423042614/http://www.quitnow.gov.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/smokescreen-lp.

A lower socio-economic bias was adopted in media placement, which reflected the social class gradient of smoking in Australia. 15 In support of the primary campaign advertising medium of television, secondary media included print advertising, radio, outdoor (billboards, bus and tram sides) and a campaign website.

For more on the National Tobacco Campaign development and implementation see: http://webarchive.nla.gov.au/gov/20140801053454/http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-publicat-document-tobccamp_3-cnt.

14.3.2.2.1 Evaluation of the 1997–2001 National Tobacco Campaign

Three evaluation volumes 16-18 and a dedicated supplement to the Tobacco Control journal 19 have published extensive research and evaluation on the campaign.

There was a significant reduction in smoking prevalence among Australian adults observed over the period of the National Tobacco Campaign. 20 Campaign surveys indicated a decline from 23.5% in May 1997 to 20.4% in November 2000. 13 It is difficult to know how much of this decline can be attributed to the National Tobacco Campaign, 12 as opposed to other tobacco control policy initiatives such as increased taxes on cigarettes 21 or other trends. Nevertheless, campaign survey findings regarding advertising recall, recognition, appraisal, new learning and changes in health beliefs and attitudes are consistent with contributing to these changes in smoking prevalence. 22

Overall, the results of campaign surveys indicated that the campaign advertising was seen and recalled by the majority of the target audience, with levels of prompted recognition of campaign advertising at approximately 90%. Approximately half of the smokers who recognised the campaign advertising reported that this had made them more likely to quit.

In addition to the annual cross-sectional surveys conducted each November from 1997 to 2000, a continuous tracking study explored the relationship between campaign advertising and measures such as awareness and response to the advertising and indicators of interest in quitting. It assessed ‘cut-through’ of campaign advertising, response to this advertising and considered levels of response generated at different levels of campaign advertising weight. 23 Unprompted recall and recognition (prompted recall) were positively related to advertising weight (measured in Target Audience Rating Points (TARPs). 24 However, it was also found that cut-through for a particular advertisement was clearly mediated by its message and creative execution. ‘Artery’, ‘Brain’ and ‘Tar’ achieved the highest cut-through per TARP of the health effects advertisements.

Further studies have since been undertaken that provide valuable information on program placement, relationship between advertising and call generation, and optimal TARP weights to inform campaign media planning—see Section 14.4.3.

Two cost-effectiveness studies 11, 25 were conducted on the initial phase of the campaign. Using the baseline survey (May 1997) and the first evaluation survey (November 1997), estimates were made regarding the reduction in number of smokers that could be attributed to the National Tobacco Campaign. From this calculation it was estimated that in its first six months of operation the National Tobacco Campaign achieved a reduction of 1.4% in the smoking prevalence, avoided 32,000 cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 11,000 cases of acute myocardial infarction, 10,000 cases of lung cancer and 2500 cases of stroke. In addition, Hurly and Matthews estimate that the National Tobacco Campaign prevented around 55,000 deaths and achieved gains of 323,000 life-years and 407,000 Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) with potential healthcare savings of $740.6 million. 25 The National Tobacco Campaign was therefore both cost saving and effective.

14.3.2.3 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission campaign 2006

In December 2005, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) launched a $9 million campaign to advise smokers that ‘light’ and ‘mild’ cigarettes are not a healthier option than smoking other cigarettes. The campaign was funded by Philip Morris, British American Tobacco Australia and Imperial Tobacco Australia as part of court-enforceable undertaking obtained by the ACCC after finding that these tobacco companies had represented that cigarettes marketed and packaged as ‘light’, ‘mild’ or similar descriptors had certain health benefits in comparison to those marketed as regular or higher yield cigarettes. 26 This campaign featured prominent television and outdoor advertising over the early months of 2006.

14.3.2.4 National Campaign and the Introduction of graphic health warnings 2006

During 2006 tobacco campaign activity increased nationally from mid-February 2006 when the Australian Government launched the first stage of its new National Tobacco Campaign to address youth smoking rates, committing $25 million over four years. 27 This initial stage focused public attention on the release of a new system of graphic health warnings on tobacco product packaging. From 1 March 2006 tobacco products manufactured or imported into Australia were required to be printed with the new health warnings images (see Chapter 12A.1). 28 This campaign was staged from February to April 2006 including the national broadcast of a television advertisement featuring a mouth and throat cancer graphic health warning.

14.3.2.5 The National Tobacco Youth Campaign 2006-2007

The second stage of the Australian Government’s new National Tobacco Campaign targeting smoking rates among young adults and teenagers was launched at the end of December 2006 and the initial phase continued until March 2007. The new campaign, featuring television, cinema, magazines, radio and outdoor advertising, graphically depicted the range of toxic chemicals in cigarette smoke and the health effects caused by them, visually tied into some of the graphic health warnings. 27 Campaign advertisements can be viewed at http://webarchive.nla.gov.au/gov/20110423040508/http://www.quitnow.gov.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/youth-lp.

14.3.2.6 The National Tobacco Campaign: 2010 to 2018

Since 2010, numerous anti-smoking advertisements and campaign materials have been run under the National Tobacco Campaign. These campaigns typically include various media channels, including television, radio, print and outdoor materials, supported by the QuitNow website: www.quitnow.gov.au. Many of the print and radio advertisements were also produced in multiple languages. Increasingly, social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter have been incorporated into a wider public relations strategy to support national campaigns. 29

Campaigns run from 2010 to 2013 focused on promoting quit attempts among smokers and preventing relapse among recent quitters. 30 Graphic health effects ads—Gangrene and Mouth Cancer—that were developed by the collaboration between states governments and state-based NGOs for the graphic health warnings campaign were aired in 2010. The 2011 campaign included a television advertisement—Cough—and radio and print materials describing the health benefits associated with quitting and featured the tagline ‘Every cigarette you don’t smoke is doing you good’. 29 Additional campaigns developed by state agencies were also aired under the National Tobacco Campaign, including Never Give Up Giving Up, Parents and The Wait from Quit Victoria; Excuses, Voice Within and Bronchoscopy from Cancer Institute NSW; Who will you leave behind from Cancer Council WA. Licensing of these state-based campaigns for national broadcast allow for a greater number of highly effective campaigns to be aired than if only new messages were developed and produced. Further advertisements targeting priority populations produced during this time are described below.

The 2014-15 campaigns aimed to reach smokers aged 18–50 years with an additional focus on vulnerable groups within the population with high smoking rates. These campaigns were designed to promote and support quit attempts. 31 ‘Stop before the suffering starts’ featured two television advertisements that depicted the health effects of smoking (‘Breathless’) and the health benefits of quitting (‘Symptoms’).

14.3.2.7 National Tobacco Campaign More Targeted Approach

Additional advertisements were produced in during this National Tobacco Campaign period under the More Targeted Approach program. This sought to complement the ‘mainstream’ National Tobacco Campaign activity with advertisements produced and aired specifically to target high-need and hard-to-reach audiences. 32 The primary advertisement of this campaign was Break the Chain, a testimonial ad featuring an Indigenous woman describing how smoking has impacted the health of her close family and friends, and her determination not to let that happen to her and prevent her from children thinking smoking-related disease is normal. Campaigns aired in 2016–17 and 2017–18 were specifically targeted at indigenous smokers and recent quitters aged 18-40 years, with additional advertisements focused on pregnant women and their partners in 2016–17. 29 These campaigns included ‘Don’t make smokes your story’, featuring an indigenous man describing his experiences with smoking and quitting. ‘Quit for you, quit for two’ encouraged and supported pregnant women to quit smoking.

14.3.3 State and territory campaigns

14.3.3.1 State-based Quit campaigns

Early state- and territory-based smoking-control activity was undertaken by the state health departments in New South Wales and Western Australia and by Cancer Councils in Victoria and South Australia. The combined finances and expertise of these groups resulted in a high standard of education campaigns and tobacco policy development in Australia.

These campaigns typically focused on a ‘Quit week’ of activities but varied their activities throughout the year. Information on smoking, advice on quitting and the opportunity to attend cessation courses encouraged smokers to quit. Young people were targeted through schools, where class resources were designed for specific age groups. The Quit organisations also provided support and resources for health professionals, including medical practitioners, to assist with counselling and to support community-based activities. In some states a ‘Quitline’ (telephone information service) was available, delivering a recorded message that advised on quitting and directed callers to trained staff for individual counselling and self-help resources.

Informed by campaign research and evaluation studies, specific population groups were identified and targeted, including children, young women, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander smokers, smokers from non-English speaking backgrounds, and older smokers. Quit groups developed and delivered programs for workplaces that required general information or guidance on becoming smokefree and programs aimed at restaurants and other public places.

Mass media campaigns and sports sponsorships were the most visible means used to promote messages about smoking and health. The Quit message was also promoted through community events such as no-smoking days or education campaigns run in schools, hospitals, worksites, health centres and other community-based venues and through press and media coverage generated by these events.

The significant investment by and cooperation between state and territory Quit organisations (which include both government and non-government agencies) has continued since the first National Tobacco Campaign. As shown in Table 14.3.1, many new campaigns have been created, focusing on a range of themes and using a variety of execution styles (e.g. testimonials, strong graphic health effects, narrative stories) and primarily targeting adults. Campaign organisations have frequently licensed these advertisements to other jurisdictions.

Details of television campaigns aired in Australia since 2001, including links to campaign advertising materials where available, are listed and briefly described in Table 14.3. This table also lists which other states and territories these campaigns have aired in since 2001.

14.3.3.2 Health promotion foundations

During the late 1980s and the 1990s health promotion foundations were established by legislation in Victoria, South Australia, the Australian Capital Territory and Western Australia. These foundations were financed by an increased levy on state or territory tobacco license fees, and shared the objectives of:

- sponsoring activities related to the promotion of health or to the prevention and early detection of disease

- increasing awareness of programs promoting good health through sponsorship of sports, the arts and popular culture

- funding research and developing activities in support of these aims.

In 1993, the Queensland Health Promotion Council was also established to fund health promotion (though promotion via funding of sports was excluded). The Tasmanian Health Promotion Council was established along similar lines in the same year.

These foundations gave rise to new opportunities, especially in their capacity to provide an alternative source of funding from tobacco companies for sponsorships of sport and the arts. They were also able to purchase advertising space (particularly on billboards and in cinemas) previously used by tobacco companies, thereby assisting the advertising industry during the transition period when tobacco advertising bans were being introduced.

Sponsorship agreements brought about major opportunities for health promotion. 33 Target groups now included participants in and spectators of sports or cultural events, who may not have been reached by previous health promotion strategies. Not only were messages about smoking prevention and smoking cessation seen more often, but the messages could also be tailored for specific audiences and adjusted to maintain a fresh and contemporary image. Importantly, the relationships that developed as a result of sponsorship contracts could also be used to encourage the adoption of changes such as policies on smokefree areas at venues, the provision of low alcohol drinks, healthy food choices and sun protection. 34

14.3.3.3 State-based graphic health warnings campaign collaboration

In 2005 the Cancer Institute NSW and Quit Victoria spearheaded a major collaborative effort between eight state and territory anti-tobacco organisations, to capitalise on the introduction graphic health warnings. The initiative aimed to extend the impact of pack warnings beyond their initial newsworthiness. The basic premise of the advertising campaign was that if graphic health warnings served to remind smokers of the health consequences of smoking every time they had a cigarette 35 then exposure to the health warnings advertisements might serve to increase the salience of these consequences.

Responding to consumer insights 36 , the most salient health effects depicted in the graphic health warnings were those that were visible outside the body. The first advertisement, ‘Amputation’, was launched in May 2006 and dramatised the graphic health warning ‘smoking causes peripheral vascular disease’. It featured a surgeon about to amputate a man’s gangrenous foot. This advertisement was followed by ‘Mouth cancer’ in July 2006. The advertisement dramatised ‘smoking causes mouth and throat cancer’ and depicted a woman with mouth cancer. Three further advertisements were launched in 2007 to capitalise on the introduction of the second set of graphic warnings and focused on a smoker’s choice of packets with different health warnings (‘Which disease?’), the graphic depiction of an operation to remove plaque from a woman’s carotid artery (‘Carotid’) and a chilling portrayal of a man’s thoughts about the consequences of his smoking after experiencing a stroke (‘Voice within’). These powerful advertisements have been broadcast by most states as components of their tobacco control programs, with heaviest exposure being bought in the most populous states of New South Wales and Victoria. These advertisements can be viewed on many of smoking and health program websites listed in Appendix 1, and, where available, through links in Table 14.3.1.

Evaluation studies showed high levels of awareness and engagement with these advertisements, and prompting of significant discussion and quitting attempts. 37 Brennan and colleagues demonstrated a complementary effect of the advertising campaign and the graphic warnings introduction. Importantly, this research provides some of the first evidence in support of a multi-faceted approach to the introduction of new tobacco control policies with the use of media campaigns to facilitate and extend understanding and impact. 38

14.3.4 International use of Australian tobacco campaign materials

Adapting or reusing mass media material from other countries is becoming an increasingly accepted practice in Australia and overseas. Many Australian states have used materials that originated in other countries such as the US and the UK. Examples include the ‘Echo’ campaign adapted and re-shot based on a successful Californian advertisement, the ‘What’s worse’ ad featuring a woman telling her children she has lung cancer, the ‘Anthony’ testimonial ad from the UK, the ‘Ronoldo’ ad from Massachusetts and the ‘Cigarettes are eating you alive’ ad from New York.

Adapting materials saves on production costs and time, enabling resources to be concentrated into broadcasting. 39, 40 This is particularly advantageous for low- and middle- income countries—Sugden and colleagues 41 give a useful discussion of the practical challenges of developing public education campaigns in limited resource settings, and the process of identifying, adapting, pre-testing, and running a television public education campaign in Tonga.

Some advertisements are more suitable for adaption than others. Those with good potential are those that have performed well in their country of origin. Ads are also more suitable for adaption and more likely to be potentially effective and acceptable to a wider audience if they have no people in them (e.g. using graphics, simulation or body parts) or have people who do not speak directly to the camera (so that a voiceover can be recorded in any language). 39, 42, 43

Adapting advertisements reduces reliance on medical knowledge and marketing expertise, which may be hard to find or ‘upskill’ in short timeframes. This approach has been used in many low and middle income countries by the World Lung Foundation using funds from the Bloomberg Initiative (see https://www.mediabeacon.org/tobacco-control/).

Some examples of successful Australian campaign exports are listed below.

- Perhaps Australia’s greatest campaign export has been the National Tobacco Campaign and specifically the ‘Artery’ advertisement. National Tobacco Campaign advertisements have been used and adapted in numerous countries around the world including Cambodia, Canada, Iceland, Mongolia, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Singapore, the US (various states), Vietnam, and Tonga.

- The ‘Sponge’ campaign (Cancer Institute NSW) has been aired in the world’s most populous nations—in India (two national campaigns, for World No Tobacco Day 2009 and 2010), Russia and China, as well as in Turkey, the Philippines, Mauritius, and Tonga.

- The ‘Carotid’ advertisement (Quit Victoria), made in 2007 in support of the new graphic health warnings, has been used by New South Wales, the Northern Territory and the state of New York and New York City.

- The ‘Bubblewrap’ campaign (Quit Victoria), produced in 2005 and aiming to educate smokers on emphysema, has been used by New South Wales, South Australia, Western Australia, Queensland and Tasmania as well as in Greece, New York City, Egypt, Poland, Russia, Turkey and China.

- The ‘Separation’ campaign (Quit Victoria), produced in 2008, which aimed to educate smokers on the impact their smoking has on others, has been used by Tasmania and in New York City, New York State, Virginia and Rhode Island in the US.

Relevant news and research

A comprehensive compilation of news items and research published on this topic

Read more on this topic

References

1. Cancer Council Victoria. Celebrating 20 years of better health: Quit Victoria 1985 - 2005. Melbourne: The Cancer Council Victoria, 2005.

2. Egger G, Fitzgerald W, Frape G, Monaem A, Rubinstein P, et al. Results of a large scale media anti-smoking campaign in Australia: the North Coast Healthy Lifestyle Program. British Medical Journal, 1983; 287:1125-8.

3. Winstanley M, Woodward S, and Walker N, Tobacco in Australia; Facts and issues 1995; Second edition. Carlton South: Victorian Smoking and Health Program; 1995.

4. Durkin S, Brennan E, and Wakefield M. Mass media campaigns to promote smoking cessation among adults: an integrative review. Tob Control, 2012; 21(2):127-138. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/21/2/127.abstract

5. Senate Standing Committee on Social Welfare, Drug problems in Australia: an intoxicated society? Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service; 1977.

6. National Campaign Against Drug Abuse. Campaign document issued following the Special Premiers’ Conference April 2, 1985. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service, 1985.

7. Blewett N. Australia's achievements and ongoing strategy in the fight against tobacco consumption, in Tobacco and health 1990: the global war. Proceedings of the Seventh World Conference on Tobacco and Health, 1-5 April 1990. Durston B and Jamrozik K, Editors. Perth, Western Australia: Health Department of Western Australia; 1990. p 6-8.

8. Research and Marketing Group. Tracking research for the Drug Offensive "Smoking. Who needs it?" campaign and evaluation of campaign sponsorship of surfing events and clinics. Drug offensive research report. Sydney: The Department of Health, Housing, Local Government and Community Services, 1983.

9. Hill DJ, White VM, and Scollo MM. Smoking behaviours of Australian adults in 1995: trends and concerns. Medical Journal of Australia, 1998; 168(5):209–13. Available from: http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/mar2/hill/hill.html

10. Wooldridge M. Preface, in Australia’s National Tobacco Campaign. Evaluation report volume one. Every cigarette is doing you damage. Hassard K, Editor Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care; 1999. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/wcms/Publishing.nsf/Content/health-pubhlth-publicat-document-metadata-tobccamp.htm/$FILE/tobccamp_a.pdf.

11. Carter R and Scollo M. Chapter 7: Economic evaluation of the National Tobacco Campaign, in Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report vol. 2 Every cigarette is doing you damage. Hassard K, Editor Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care; 2000. p 201-38 Available from: http://www.quitnow.gov.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/national-tobacco-campaign-lp

12. White V, Hill D, Siahpush M, and Bobevski I. How has the prevalence of cigarette smoking changed among Australian adults? Trends in smoking prevalence between 1980 and 2001. Tob Control, 2003; 12 (Suppl 2):ii67-74. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12878776

13. Wakefield M, Freeman J, and Inglis G. Ch 5 Changes associated with the National Tobacco Campaign: results of the third and fourth follow-up surveys, in Australia's National Tobacco Campaign; evaluation report Vol. 3. Hassard K, Editor Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing; 2004. Available from: http://www.quitnow.info.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/evaluation-reports.

14. Hill D and Carroll T. Australia's National Tobacco Campaign. Tob Control, 2003; 12(suppl. 2):ii9–14. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/12/suppl_2/ii9

15. National Public Health Partnership. Preventing Chronic Disease: A Strategic Framework. Melbourne: National Public Health Partnership, 2001.

16. National Tobacco Campaign Research and Evaluation Committee. Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report vol. 1 Every cigarette is doing you damage. Canberra, ACT: Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy, 1999. Available from: http://www.quitnow.gov.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/national-tobacco-campaign-lp.

17. National Tobacco Campaign Research and Evaluation Committee. Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report vol. 2. Every cigarette is doing you damage. Two Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, 2000. Available from: http://www.quitnow.gov.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/national-tobacco-campaign-lp.

18. National Tobacco Campaign Research and Evaluation Committee. Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report vol. 3. Every cigarette is doing you damage. Three Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, 2004. Available from: http://www.quitnow.gov.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/national-tobacco-campaign-lp.

19. Woodward A. Insights from Australia's National Tobacco Campaign. Tob Control, 2003; 12(suppl 2):ii0. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/12/suppl_2/ii0.short

20. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Statistics on drug use in Australia 2004. Cat.No. PHE62. Drug Statistics Series No.15, Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2005.

21. Scollo M, Younie S, Wakefield M, Freeman J, and Icasiano F. Impact of tobacco tax reforms on tobacco prices and tobacco use in Australia. Tob Control, 2003; 12 Suppl 2:ii59-66. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12878775

22. Wakefield M, Freeman J, and Donovan R. Recall and response of smokers and recent quitters to the Australian National Tobacco Campaign. Tob Control, 2003; 12(suppl. 2):ii15-ii22. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/cgi/content/abstract/12/suppl_2/ii15

23. Donovan R, Freeman J, Borland R, and Boulter J. Tracking the National Tobacco Campaign, in Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report Vol. 1. Hassard K, Editor Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care; 1999. p 127-87 Available from: http://www.quitnow.info.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/evaluation-reports.

24. Donovan RJ, Boulter J, Borland R, Jalleh G, and Carter O. Continuous tracking of the Australian National Tobacco Campaign: advertising effects on recall, recognition, cognitions, and behaviour. Tob Control, 2003; 12(suppl. 2):ii30–9. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/12/suppl_2/ii30

25. Hurley SF and Matthews JP. Cost-effectiveness of the Australian National Tobacco Campaign. Tob Control, 2008; 17(6):379-84. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/cgi/content/abstract/17/6/379

26. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. Low yield cigarettes 'not a healthier option': $9 million campaign., Canberra: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, 2006. Available from: http://www.accc.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemId/719575

27. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Background on the national Tobacco Youth Campaign. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, 2006. Last update: Viewed Available from: http://www.quitnow.gov.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/youth-lp.

28. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Graphic Health Warnings: labelling of tobacco products. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2006. Available from: http://www.quitnow.info.au/internet/quitnow/publishing.nsf/Content/warnings-lp

29. Australian Government Department of Health. National Tobacco Campaign: The history of the National Tobacco Campaign. Canberra 2018. Last update: Viewed 22 July 2019. Available from: http://webarchive.nla.gov.au/gov/20190208165138/http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/tobacco-educat.

30. Australian Government Department of Finance. Campaign Advertising by Australian Government Departments and Agencies Full Year Report 2011–12. 2012. Available from: https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/full-year-report-2011-12.pdf .

31. Australian Government Department of Finance. Campaign Advertising by Australian Government Departments and Agencies Annual Report 2014-15. 2015. Available from: https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/campaign-advertising-by-australian-government-departments-and-agencies-annual-report-2014-15.pdf

32. Australian Government Department of Finance. Campaign Advertising by Australian Government Departments and Agencies Annual Report 2013-14. 2014. Last update: Viewed Available from: https://www.finance.gov.au/sites/default/files/advertising-annual-report-2013-14.pdf?v=2.

33. Holman C, Donovan R, Corti B, Jalleh G, Frizzell S, et al. Banning tobacco sponsorship: replacing tobacco with health messages and creating health-promoting environments. Tob Control, 1997; 6(2):115−21. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1759553&blobtype=pdf

34. Holman CDJ, Donovan RJ, and Corti B. Report of the evaluation of the Western Australian Health Promotion Foundation. Department of Public Health and Graduate School of Management., Perth: The University of Western Australia, 1994.

35. Borland R, Yong H, Wilson N, Fong G, Hammond D, et al. How reactions to cigarette packet health warnings influence quitting: findings from the ITC Four-Country survey. Addiction, 2009; 104(4):669-75. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19215595

36. Murphy M. Cigarette pack warning labels. Report of exploratory qualitative research for Quit Victoria and Cancer Institute NSW. Melbourne: Market Access Consulting and Research Pty Ltd, 2005.

37. Quit Victoria and The Cancer Institute NSW. Health warnings campaigns. Sydney: Quit Victoria and The Cancer Institute NSW, 2007.

38. Brennan E, Durkin SJ, Cotter T, Harper T, and Wakefield MA. Mass media campaigns designed to support new pictorial health warnings on cigarette packets: evidence of a complementary relationship. Tob Control, 2011. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2011/04/07/tc.2010.039321.abstract

39. Cotter T, Perez D, Dunlop S, Hung WT, Dessaix A, et al. The case for recycling and adapting anti-tobacco mass media campaigns. Tob Control, 2010; 19(6):514-17. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/19/6/514.abstract

40. World Health Organization. MPOWER: A policy package to reverse the tobacco epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008. Available from: https://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/mpower_english.pdf.

41. Sugden C, Phongsavan P, Gloede S, Filiai S, and Tongamana VO. Developing antitobacco mass media campaign messages in a low-resource setting: experience from the Kingdom of Tonga. Tob Control, 2017; 26(3):344-348. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/tobaccocontrol/26/3/344.full.pdf

42. Durkin S, Bayly M, Cotter T, Mullin S, and Wakefield M. Potential effectiveness of anti-smoking advertisement types in ten low and middle income countries: do demographics, smoking characteristics and cultural differences matter? Social Science & Medicine, 2013; 98:204-23.

43. Wakefield M, Bayly M, Durkin S, Cotter T, Mullin S, et al. Smokers’ responses to television advertisements about the serious harms of tobacco use: pre-testing results from 10 low- to middle-income countries. Tob Control, 2013; 22(1):24-31. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21994276