Innovations in product and packaging design have become increasingly important to the tobacco industry as a means of communicating with the consumer, as other avenues of promotion have closed and concerns about the health effects of smoking have become stronger.1-3 This section identifies these developments in Australian and international markets, particularly focusing on factory-made cigarette and roll-your-own (RYO) tobacco, including trends observed on fully branded packs, plain packs, and during the transition from branded to plain packs in Australia. Product and packaging innovations that are intended to attract consumer interest and gain market share are described here; detailed information about the engineering of cigarettes and tobacco additives can be found in Chapter 12; information about new developments in e-cigarettes can be found in Section 18.1. A detailed discussion of packaging as promotion and plain packaging as a regul atory response is located in InDepth 11A.

10.6.1 Using the pack to target consumer groups

Aside from the functional aspects of packaging, the design of a tobacco pack can be “used to promote the product, distinguish products from competitors, communicate brand values and target specific consumer groups” and has “wider reach than advertising and is the most explicit link between the company and the consumer”.4 (p5)

Researchers in the UK comprehensively documented changes to tobacco packaging that were observed following the implementation of bans on print and outdoor advertising, promotion, and sponsorship.4-7 They identified four key packaging strategies that aimed to target particular consumer groups:

- value-based packaging

- image-based packaging

- novel or innovative packaging

- environmentally sustainable (‘green’) packaging

These packaging strategies are described below, including examples from Australia and other countries. Trends in product design that may target specific consumer groups is described in Sections 10.6.4 and 10.6.7.

10.6.1.1 Conveying value for money through the pack

Tobacco packaging can be configured to convey value for money or budget options through the design elements of the pack itself, or through the availability of different pack sizes.

Smaller pack and pouch sizes

Offering products in small pack sizes provides options with a low upfront cost or price point. Small packs of budget brands (also called value and super-value brands in Australia) offer the cheapest possible purchase for consumers, while a low upfront purchase price may be desirable for price-sensitive young smokers looking to purchase a premium brand.4 Packs of 20 cigarettes are the norm in most countries. However, in the UK packs of five small filter cigars have been available since at least the early 2000s,5 and the range of factory-made cigarette pack sizes below 20s grew to include 10s, 14s, 17s, 18s, and 19s. The UK’s plain packaging legislation, in line with the EU Tobacco Products Directive, restricts minimum pack size to 20 cigarettes.

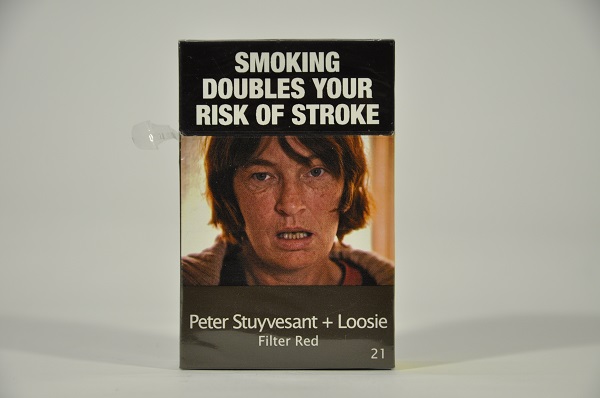

In Australia, packs must also contain a minimum of 20 cigarettes. Most brands, including budget through to premium brands, offer a pack of 20s. Shortly before the implementation of plain packaging, a trend toward offering packs with ‘bonus’ cigarettes was observed, where the budget brands Holiday and Horizon offered packs of 21s and 22s for a similar price to the standard 20s pack, and brands such as JPS and Bond Street offered packs of 26s for similar prices to traditional packs of 25s.8 The premium brand Peter Stuyvesant also introduced a “ + Loosie” range of packs of 21s and 26s—see Figure 10.6.1; ‘loosie’ is a slang term for a single cigarette sold individually.9 Conversely, following large annual tobacco tax increases, the premium brand Dunhill replaced all packs of 25s with 23s. In effect, the retail price of 23s was essentially the same following the September 2016 12.5% tax increase as the pre-increase price of 25s.10,11

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

RYO pouches in increasingly small sizes have also emerged on the Australian and UK markets—see also Chapter 10, Section 10.9.5.1. Pouches as small as 8 grams (also 9, 10, 12.5, 20, and 25 grams) have been available for sale in the UK. In Australia, traditionally most RYO tobacco pouches were available in 30 gram pouches or larger, with 50 grams the most common RYO pouch size. Since approximately 2013, an increasing number of brands have offered RYO products with increasingly low up-front purchase prices, first 25 gram pouches, then 20 grams introduced in 2015; 27 gram pouches are also available.12 Online Australian retailers also offer 10 gram ‘sampler’ pouches of flavoured tobacco.11 One RYO brand has also used the variant name to imply value for money: JPS RYO products are available in Eternal Red, Endless Blue, and Abundant Gold—conveying a sense of plentiful numbers of cigarettes that can be made from the tobacco in each pouch—while JPS factory-made cigarettes are available in the more simple variants Red, Blue, and Gold.

Larger pack and pouch sizes

Australia’s unusual tobacco tax system, amended in 1999, resulted in increasing large factory-made cigarette pack sizes being available on the market: first 25s, then 30s, 35s, 40s, and 50s—see Chapter 13, Section 13.3 for more information. Larger cigarette pack sizes typically offer better value per stick than smaller packs, even for premium brands. Most Australian brands offer packs in at least two sizes, although budget brands typically have a larger range, such as 20s, 25s, 30s and 40s and/or 50s. Since approximately 2015, an increasing number of mainstream (mid-priced) and premium brands have also offered a larger range of pack sizes, including Benson & Hedges 30s in 201512 and Winfield 40s and Peter Jackson 40s, seen in supermarkets in 2017.

As noted above, RYO pouches in Australia have typically been available in 50 grams, with a trend toward smaller pouches becoming evident since 2013. In contrast, larger pouch sizes were introduced in the UK around 2010.4 Consumers generally perceive that larger pack sizes offer a discounted per unit price compared to smaller packs from the same product,4 but this is not necessarily the case for RYO products in Australia. For example, the 2017 per gram recommended retail price of Port Royal 25 gram and 50 gram pouches was $1.33 and $1.32, respectively13—a discount of $0.25 compared to buying two 25 gram pouches.

Pack designs which communicate value

Simply packaged, ‘no frills’ or home-brand style cigarette brands were introduced to the Australian market in 2006 with the brand Choice (Philip Morris). Following a large increase in excise duty in April 2010, and shortly before implementation of plain packaging implementation in 2012, a range of other budget, no frills brands were introduced, including Bond Street (Philip Morris) and Just Smokes (BATA)14—see Figure 10.6.2. Additional heavily discounted, simply packaged brands including Deal and Easy, were imported by Richland Express exclusively for the national supermarket chain Coles as a ‘home brand’.15

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

Revamping packaging of brands traditionally seen as 'value'

In contrast to using simple pack designs to communicate value in relatively new products, the packaging of well-established value brands may be revamped periodically. Pack redesigns can provide a sense of innovation, that the brand is ‘modern and fresh’.4 In the UK, examples include redesign of Gallaher's Mayfair brand and British American Tobacco's Royals and Windsor Blue with a new silver logo in January 2006.

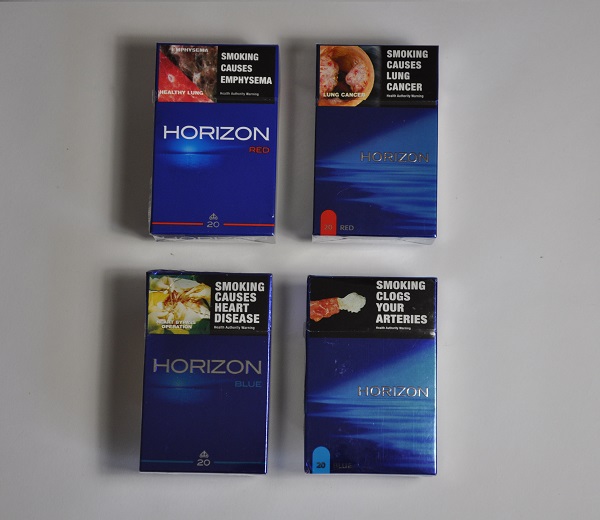

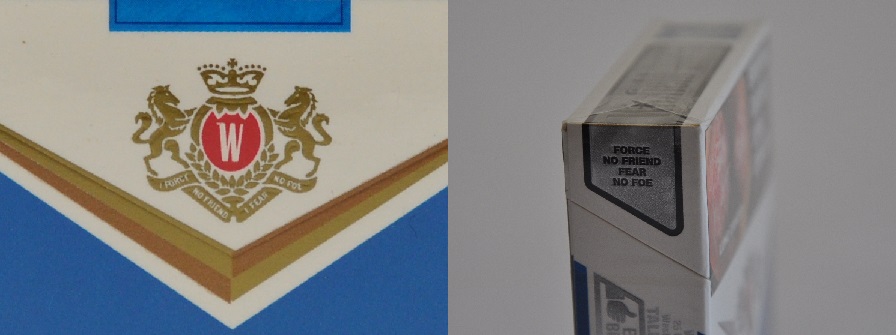

A series of retail trade advertisements in 1997, 2004, and 2008 promoted packaging redesigns for the popular Australian value brand Horizon.16-18 Each advertisement featured a reassurance message that only the packaging was changing, not the product or flavour, e.g. “Remember, while our pack design may be changing, Horizon cigarettes remain the SAME GREAT QUALITY SMOKE!”.17 The 2004 advert highlighted the benefit of the packaging changes for retailers—“much easier to identify”—while the 2008 redesign was more comprehensive, including the “striking” pack, “sleek” stick, and “fresh” foil.18 Shortly before plain packaging implementation in 2012, Horizon packs underwent another packaging revamp—see Figure 10.6.3.

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

In 2007, the brand extension Holiday Slims was completely rebranded within a different brand family: Pall Mall Slims. Both Holiday and Pall Mall are British American Tobacco Australia value brands. The new Pall Mall Slims had a highly feminine pack design. Prior to the transition, Holiday Slims packs were printed with a banner to communicate the upcoming change to consumers. Retail trade promotional material noted that:

“…Holiday Slims smokers are:

- Very loyal to a slim cigarette but not necessarily loyal to the Holiday Slims brand

- Excited about the move to Pall Mall Slims which they see as more modern, fun and with an attractive pack”

Introducing Pall Mall Slims, Australian Retail Tobacconist, June/July 2007: 68(4)

Price-marking (printing the price on the brand) to imply a 'special' low price

Price-marked packs, where the retail price is printed on the pack itself (Figure 10.6.4) is a price-promotion strategy that has successfully increased sales in the UK.4 Price-marked packs imply a special or discounted price, even though the marked price may simply be the recommended retail price. A study of tobacco retailers in England found some retailers reported lower profits from price-marked packs.19 In addition to conveying price information to consumers, price marking has the effect of setting a consistent retail price, sometimes being referred to by retailers as “price-locked” packs.19

Price-marking has not been observed in Australia, but in the UK it has included Basic Superkings in 2005, John Player Specials and King Edward Coronets in 2006 and Golden Virginia smoking tobacco in 2008.5 Price-marked packs are prohibited in the UK’s plain packaging legislation.

Source: Ford, 2012.4

10.6.1.2 Conveying quality, sophistication, and innovation through the pack

Image-based packaging

Image-based packaging refers to the graphical (colours, fonts, logos and other visual elements) and structural elements (packaging materials, pack shape), and can include design elements aimed at appealing to specific segments of the market, in particular younger and female smokers (see below). Image-based packaging confers product attributes to consumers, reinforces brand imagery and associations, and attracts new consumers.4

Tobacco companies in both the UK and Australia redesigned the livery of many brands between 2004 and 2010. Moodie and Hastings have compiled extensive materials highlighting changes in brands documented in the British advertising trade press over that period.5 More recent image-based packaging redesigns include Gallahar’s 'tweaking' of the design of Benson & Hedges Gold and Silver in the UK (reported in The Grocer in January 2009). The redesigned brands featured a modernised typeface and logo, and the brand’s red seal was replaced with a new triangle design.5 In Australia, subtle changes to cigarette packs and trademarks were also observed on Benson & Hedges packs as early as 2002.20 When researchers called the company to enquire about the changes, an employee said they were “playing with the logo because we can't do any advertising any more”.20

One of the most striking examples of image-based package redesign is that of Dunhill. In June 2005 in the UK, The Grocer magazine reported that a new Dunhill logo had been created and that the royal coat of arms had been simplified and reduced in size.21 According to the article, Dunhill’s rebranding included a new look and taste aimed at 20–35 year old smokers. The packaging was designed to give a modern aspirational image.5,21

British American Tobacco Australia has also experimented extensively with packaging for Dunhill, particularly since 2006 (at which time graphic health warnings taking up 30% of the front and 90% of the back of the pack were introduced in Australia). Over the years, conservative packaging for Dunhill was replaced with a slick, contemporary metallic range of packs with bevelled similar to the appearance of modern consumer goods such as iPods—see Figure 10.6.5.

Source: Simon Chapman collection and Quit Victoria pack collection

Packaging to target young and female smokers

While young smokers are particularly price sensitive, they are also often attracted to more sophisticated, mature, or innovative packaging designs.4 Products that aim to target youth may therefore include premium brands available in smaller pack sizes, providing a lower upfront price point. Packaging aimed at females often include long slender packs (including so-called lipstick packs), with pale colours and ‘clean lines’.4 Several brands sold in Australia have clearly been designed to appeal to young women—tall, slim packets of Vogue Superslims and Dunhill Essence by British American Tobacco, and Davidoff with its elegantly bevelled edge sold by Imperial Tobacco being notable examples.

Other brands would seem to appeal to an even younger female market. Trojan Tobacco Company's DJ Mix Special Feel Strawberry (pictured in Figure 10.6.6, bottom right), Lemon Fresh and Ice Green Apple appeared in the Australian Retail Tobacconist price lists between August 2005 and January 2012. Peel Menthol Orange flavoured cigarettes (top left) appeared between August 2005 and January 2009. Sobranie brightly coloured novelty cocktail cigarettes (each cigarette a different colour) appeared on price lists in February 2007 and was still listed in July 2012.22 Red Fortune Bamboo manufactured by Imperial Tobacco with its 'Asian chic' package design was introduced early in 2011.23

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

10.6.1.3 Innovative or novel packaging

Related to image-based packaging, innovative packaging is a widely-used marketing strategy, particularly to target young smokers. As cited by Ford, Moodie and Hastings:

“Jugger (1999) argues that the best way to obtain competitive advantage in an overloaded consumer goods market is through innovation in packaging. Innovative packaging is thought to change perceptions and create new market positions (Rundh 2005) and represents a shift in focus from graphic design towards the structural design of packaging (van den Beg-Weitzel and van de Larr, 2006)”

Ford, Moodie and Hastings, 20127 p341

Moodie and Hasting5 and Ford, Moodie and Hastings7 outline numerous innovations in packaging design:

- Novel ways of opening the pack

- Novel shaped and sized packs

- Novel pack materials

- Themed packs to encourage collection of sets (also limited edition packaging).

Novel ways of opening the pack

The British trade magazine Convenience Store reported in 2006 that Benson & Hedges had introduced a silver pack that slid open horizontally to replace the conventional flip top box, to which manufacturer Gallahar later attributed a 46.5% increase in sales of that brand.7 In the same month, The Forecourt Trader reported that Golden Virginia smoking tobacco had been launched in 14 gram cigarette-style packs, each containing two individually wrapped blocks of tobacco.24 The design allowed the box to hold rolling papers, filter tips and a lighter once one of the blocks was removed. In Canada, slide or push packs—see Figure 10.6.7—have been available, where the inner component of the pack containing the cigarettes is covered by an outer sleeve containing the brand, tax stamp, and health warning information. Design elements and consumer messages can be printed on the available inner surface.

Source: Tilson, M, Non-Smokers' Rights Association, Canada 2017

British American Tobacco Australia introduced Dunhill split-packs in Australia in October 2006.25 The pack could be split along a perforated line to create two mini packs, easily shared between two smokers perhaps unable to afford a full pack (Figure 10.6.8). Once split, one of the two packs did not bear the mandatory graphic health warning. BATA was forced to remove the packets from the market when it was found to be in breach of tobacco product labelling laws.26 It also marketed a range with spring-loaded lids with internal pop-ups as well as double-sided cases.

Source: ASH Australia, 2006

Novel shaped and sized packs

A study by Borland, Savvas, Sharkie and Moore conducted in Australia in 201127 found standard packs were ranked significantly less attractive and of lower quality than bevelled and rounded packs. Standard packs were less distracting to health warnings and pack openings affected perceptions of quality of cigarettes and extent of distraction from warnings. The standard flip-top was rated significantly lower in distracting from warnings than all other openings.

The UK trade magazine Convenience Store reported in March 2007 that British brand Silk Cut Graphite would be sold in a pack with a silver bevel edge designed to give a masculine appeal. Then The Grocer reported that, in November 2008, Silk Cut introduced a limited edition pack in a hexagonal shape.5 Later Silk Cut was released in textured packaging as a 'touch' pack ( Off Licence News 2010 cited in Ford, Hastings and Moodie7).

Novel pack materials

Novel pack materials seen in the UK and Australia have typically been reusable tins. Convenience Store reported in September 2006 that Amber Leaf tobacco would be available in the UK in retro-style tins. Special edition Lambert & Butler tobacco has also been sold in tins.5

In February 2006, one month prior to the adoption of picture-based warnings on tobacco packages in Australia, Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes were being sold in 'trendy retro-style tins' which, unlike soft packets of cigarettes with on-pack printed warnings, had health warning stickers that were easily peeled off28 (Figure 10.6.9). Retailers reported that the tins were very popular with younger smokers. Similar ‘vintage’ tins were offered for Imperial Tobacco’s Champion Legendary Ruby tobacco—see for example Figure 10.6.10.

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

Limited edition series and themed packs

Limited edition packaging utilised image-based and innovative packaging strategies. These might coincide with particular events, seasons, or holidays, or the introduction of a new product range, or may be a means of attracting consumer attention or offering a collectable product.4

Examples of limited edition and themed packaging in the UK include images of motor car racing on packs of Marlboro in 2005,7 Camel Art packs featured an eye-catching art-deco design attempting to emphasise the style and quality of the brand in 2006, a series of 'Cityscapes' themed designs on Sovereign packs in 2009,29 and a special edition Lambert & Butler holographic pack to mark 10 years as one of the leading cigarette brands in the UK.30 In January 2009, The Forecourt Trader reported that Golden Virginia smoking tobacco was being sold in a series of limited-edition 14 gram packs featuring eight different leaf designs.24

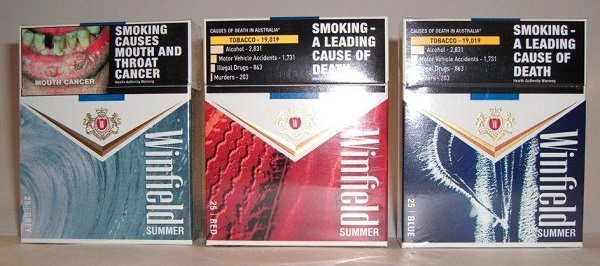

Limited edition packs have also been sold in Australia. The leading brand Winfield experimented with limited edition packs in Australia with its 'blokey' (masculine) series in 2004, then again with its summer series in 2010 (Figures 10.6.11a-b). Another BATA brand, Dunhill, also experimented with limited edition series over the 2000s. Figure 10.6.12 shows a retail trade advertisement promoting the Dunhill Signature limited edition range, to celebrate the brand’s 100th anniversary. The advertisement notes the “sleek and ultra-modern” pack design, promising retailers increased sales, and highlighting the limited availability of the packs.

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

In India in 2012, Imperial Tobacco Company introduced collector packs for the Flake brand featuring artwork by prominent artist Paresh Maity.

31

Source: Reproduced with the kind permission of the Business Standard, India

10.6.1.4 ‘Green’ or environmentally-friendly packaging

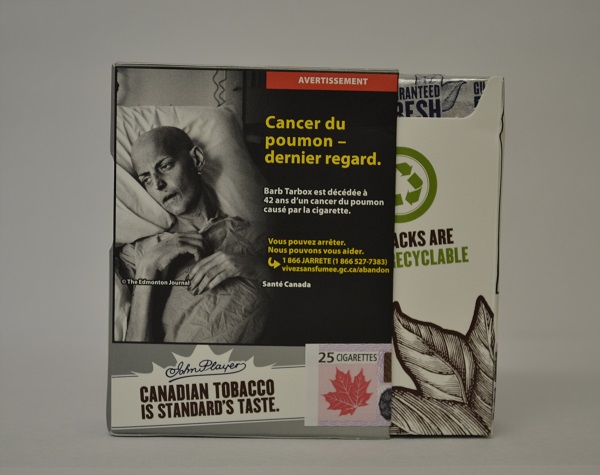

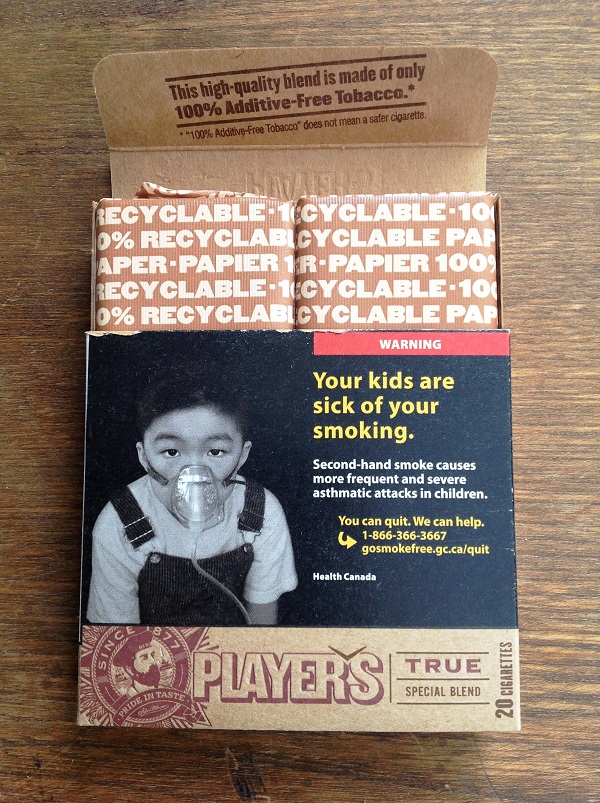

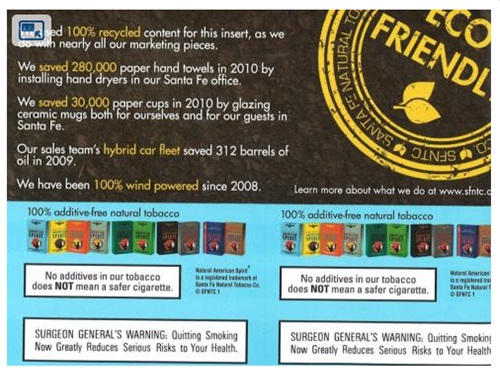

Ford, Moodie, and Hastings7 document a number of cases of sustainable packaging in the UK, for instance use of rolling tobacco papers from plantation forests. In the UK, Rizla rolling papers are certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), with the scheme's logo marked on packaging. In Australia, a range of natural-sounding rolling tobacco accessories are available, including filters and rolling papers labelled as ‘unbleached’ or ‘raw’, or made from cotton or hemp. A striking example of environmentally-friendly packaging comes from Canada, where Players True Special Blend cigarettes are packaged in an unbleached cardboard pack, with the cigarettes wrapped in “100% recyclable paper”. Figure 10.6.14 also shows that the pack is labelled “100% additive-free tobacco”, further tapping into a trend toward natural-sounding tobacco products—see Section 10.6.1.4. Efforts by tobacco companies to promote environmentally-friendly packaging have been labelled as ‘greenwashing’, where companies attempt to create positive environmental associations with their products to distract or atone for other ‘controversies’.32

Source: Tilson, M, Non-Smokers' Rights Association, Canada 2017

10.6.2 Using the pack to distract from consumer information

Packaging design can distract from consumer information in at least two ways: first by communicating misleading messages about the relative harms of products, and secondly by distracting from health warnings.

10.6.2.1 Packaging that conveys varying levels of harm

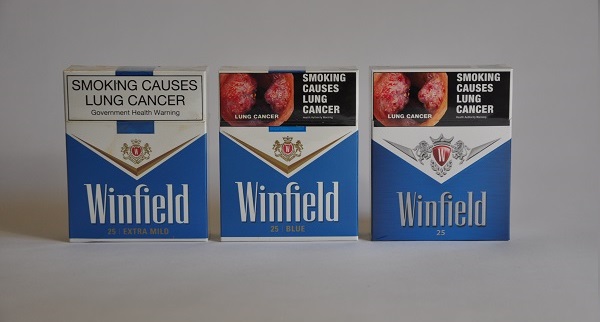

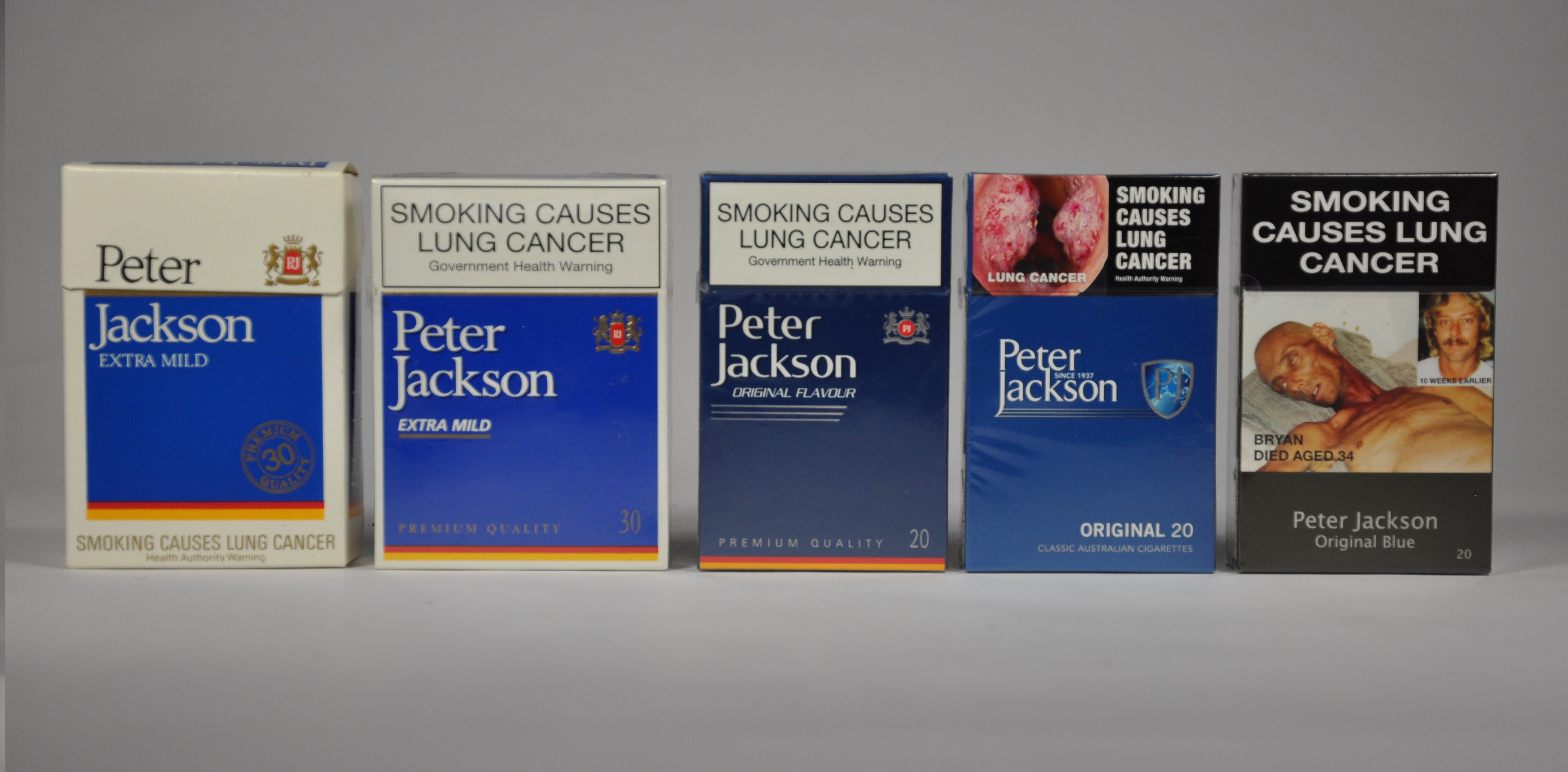

The descriptive terms 'light' and 'mild' were removed from packs in Australia in 2005 following settlement of legal action concerning misleading advertising by tobacco companies initiated by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission—see Chapter 16, Section 16.2.1. The industry responded by developing colour-coded packages with new terms. Variant ranges within cigarette brands had long been distinguishable by pack colour, with lighter colours typically representing lower tar cigarettes and green representing menthol. However, with the removal of light and mild descriptors and tar milligram numbers, tobacco companies replaced the banned components of the variant name with coloured labels, reinforcing the already established association between colour and taste or strength,33-35 and perceptions that some cigarettes are less harmful than others.36 For example, Winfield Filter 16mg became Winfield Red, Winfield Extra Mild 12mg became Winfield Blue (see Figure 10.6.15), and Winfield 2mg became Winfield White. With many different cigarette offerings in the market, pack colour provides a “simple yet familiar cue for consumers to visually differentiate between the enormous range [of products]”.14 (p.e70)

Note that “12mg” was printed on the top of the pack prior to the light and mild descriptor ban (left pack).

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

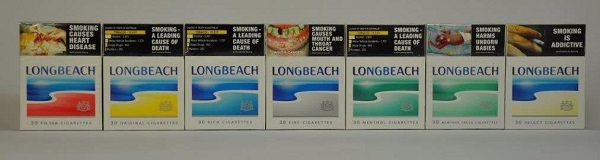

Other (mostly premium) brands—while still utilising strength-associated colouring on the pack—replaced light and mild descriptors with adjective-based variant names.37 For example, Benson & Hedges Classic replaced Special Filter 16mg; Benson & Hedges Subtle replaced Lights 6mg; and Benson & Hedges Fine replaced Ultra Mild 4mg. Philip Morris’ Longbeach also used a combination of visual pack colour, incorporated into the brand’s beach imagery—see Figure 10.6.16—and adjective descriptors across the variant range. Design elements appearing on the pack can also be varied to communicate differing levels of strength (or harm). For example, in South Korea, the iconic Marlboro ‘rooftop’ design has been observed to be larger on packs with higher tar yields.36

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

Figure 10.6.17 (see below) also shows that Philip Morris’s Peter Jackson incorporated the pre-plain packaging pack colour into the variant name post-plain packaging, so that Peter Jackson Original became Original Blue. This has been common practice for many brands.8,14

10.6.2.2 Packaging that overshadows or camouflages health warnings

International packaging manufacturers and designers remained optimistic about opportunities to increase the appeal of cigarette packs despite the intrusive health warnings introduced in many countries from the early 2000s—see Chapter 12A1 Health warnings, Section 12A1.2.

In January 2006, packaging consultant Christian Rommel wrote in the World Tobacco magazine of several possible approaches to dealing with the “eyesore that is the death notice”... “First, to ignore it, second to conceal it, third, to caricature it.” With regard to the first option, he writes:

“... in order to produce an attractive counterpoint to the omnipresent and gloomy statements, designers dig deep into the refinement box. Working with elaborate blind or imprinted laminations, special neon, metallic or fluorescent colourings, pearlescent print underneath or overprinting, iridescent laminations, haptically appealing serigraphy, three-dimensional holograms, solid-coloured papers or even cuttings.”

Rommel, World Tobacco January 200638 p17

With regard to the second option Rommel describes concealing the pack through “labels or carton covers in the necessary size, colour format and design” or by offering for sale refillable “plastic, aluminium or leather cigarettes cases for an extra charge.”38 p17

Regarding the third option—caricature—Rommel states:

“Is it even acceptable to make fun of the health warnings? Is it politically correct to ridicule them? Is it allowed to make persiflage of these warnings which with respect to human health are absolutely justified? Obviously the act of smoking involves playing with fire, but do we really need to utilize this fact in the package design? On the other hand, why not?”

Rommel, World Tobacco January 200638 p17

Rommel's proposed solution to the problem of the health warnings is to “actively engage with its limitations”.

“The motto could read: "Do not exclude but incorporate." The health warnings could be used as elements within the design. Instead of desperately trying to ignore or conceal them, it could be an entirely novel approach to engage creatively with them.

“It might even be the case that the force of government legislation will bring about an entirely new breed of fascinating cigarettes packages that might once again be worth collecting.”

Rommel, World Tobacco January 200638 p18

The package design of many major brands in Australia changed subtly in typeface, colour or design in or shortly after 2006, following the introduction of graphic health warnings taking up 30% of the front of cigarette packs—see Figure 10.6.17 (also Figure 10.6.15) and Chapter 12A.1 Health warnings.

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

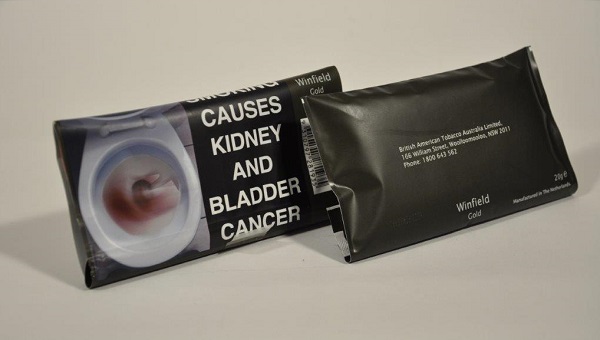

In line with Rommel's proposition, several brands included slogans on packaging which appeared to flout the idea of reducing risks to health, for instance the inclusion of the 'Force No Friend; Fear No Foe' motto on the side of Winfield packs newly designed in 2010 (Figure 10.6.18). The motto 'I Force No Friend; I Fear No Foe' previously appeared in earlier pack designs (in packs bearing the 1996-style health warnings) in very small lettering underneath the Winfield crest.

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

10.6.2.3 Packaging that enables removal of the health warning

In February 2006, one month prior to the adoption of picture-based health warnings on tobacco packages in Australia, Peter Stuyvesant cigarettes were being sold in 'trendy retro-style tins' which, unlike soft packets of cigarettes with on-pack printed warnings, had health warning stickers that were easily peeled off28 (Figure 10.6.19). Retailers reported that the tins were very popular with younger smokers.

Source: ASH Australia 2006

Cigarette packs and RYO pouches have been identified in Australia that allow smokers to remove the large graphic health warnings from some plainly packaged products.11 In 2016, Imperial Tobacco produced packs of Peter Stuyvesant Originals where the foil insert covering the cigarettes could be easily removed from the cardboard packs, leaving a plain silver ‘soft pack’ (Figure 10.6.20). At around the same time, BATA introduced zip-lock closures to their RYO pouches “to maintain product freshness once opened”39 (p5) . These allow the pack to be sealed closed much closer to the opening of the pouch, rather than wrapping the front flap (which contains the large graphic health warning) around the pouch and sealing it with a sticky tab. This means the front flap could be snipped off, leaving a neat, sealed plain pouch without the health warning—see Figure 10.6.21).

Source: Scollo et al. 201711

Source: Scollo et al. 201711

10.6.3 Branding and visual design elements on the cigarette stick

In addition to the design of the cigarette itself (such as diameter and length) and innovative features within the filter—see Sections 10.6.6 and 10.6.7—the cigarette and filter wrapping paper provide ‘real estate’ for branding and design elements, providing appeal and novelty, and reinforcing design elements from the pack itself. If the pack provides an opportunity for frequent branding exposure to the smoker, the cigarette itself does so even more frequently.40 Filter materials and design may confer positive product associations, and also influence perceptions of harmfulness. Even the choice of filter tipping paper colour—usually white or ‘cork’—can impact perceived health risk, with white-tipped cigarettes rated by current smokers as significantly less dangerous than cork-tipped cigarettes.41

Smith and colleagues examined40 more than 3000 cigarette products obtained in 2013 from 14 low-and-middle income countries—where increasing advertising and promotion restrictions are leading to more innovating packaging—and identified numerous design elements that may appear on cigarettes and filters:

- Brand name written on the stick (usually in the brand font)

- Variant name or other product descriptor written on the stick (e.g. light)

- Brand logo or other brand images printed on the stick

- Colour and design elements from the pack printed on the stick

- Flavour capsule symbols printed on the filter, indicating where the filter should be squeezed to release the flavour—see Section 10.6.4.1.

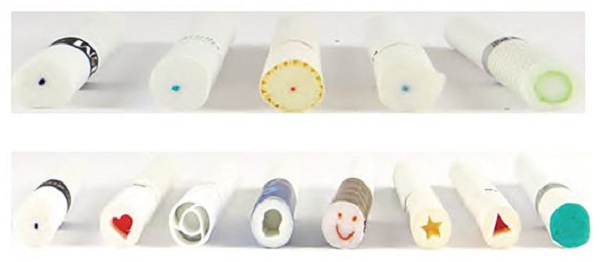

- Coloured or embellished filter tips, including images and cut-outs within the filter material itself—illustrated in Figure 10.6.22.

Source: Smith et al., 201640

10.6.4 Flavoured cigarettes and tobacco

It has long been industry practice to add ingredients to alter the flavour of tobacco. For example, menthol variants of many brands have been available for decades. Menthol additives improve the palatability of inhaled smoke by providing sensations of coolness and smoothness.42 Most major Australian factory-made cigarette and many RYO tobacco brands offer at least one menthol variety. Several large brands have also offered graded levels of menthol strength, such as Holiday Cool Blast Frost, Chill, and Blast, and others offer several variants with menthol flavouring, for example, Horizon Menthol Yellow, Menthol Blue (that is, different cigarette ‘strengths’ not amount of menthol). Some brands have previously used symbols on the pack to communicate the varying levels of menthol—see Figure 10.6.23. Menthol flavour is typically added to the tobacco from peppermint extract, although a novel, more natural-sounding menthol product was released in Australia in 2012 (but was discontinued about 12 months later). These Horizon Fusions reportedly consisted of mint leaves mixed through the tobacco.8

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

Fruit and confectionary flavoured tobacco products that may appeal to children were effectively banned from sale in Australia in the late 2000s—see Section 12.6.3.1 for more information on flavouring additives. Other flavoured tobacco cigarettes such as kreteks (clove cigarettes) are not banned. Two major Australian brands produced by Philip Morris launched kretek varieties in 2015—Longbeach and Marlboro—although these were short-lived.11

10.6.4.1 Menthol and flavour capsule cigarettes

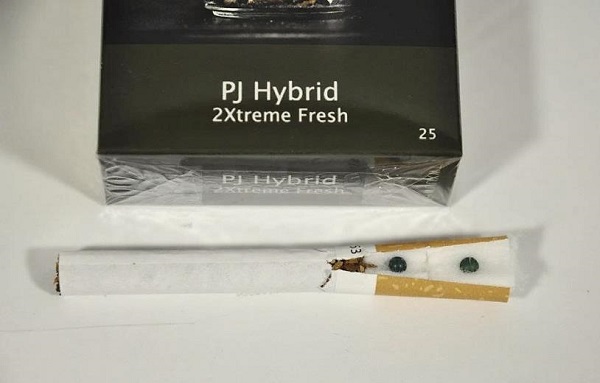

Internationally and in Australia many brands have introduced cigarettes with a capsule of menthol flavouring in the filter. Users can squeeze or crush the capsule to release the menthol flavour before, during, or toward the end of smoking—also referred to as ‘flavour on demand’ products.43 The capsule provides a multisensory experience for the smoker: crushing the capsule provides a tactile response, a ‘popping’ sound, and changes the flavour and aroma of the cigarette.44 Capsules with other flavourings and multiple flavour capsules are also available internationally.45 In many markets, products with flavour capsules were typically first introduced within premium brands’ product ranges. Capsule products have since been introduced more broadly across different market segments in an effort to provide a premium feature across even budget brands.46

Capsule cigarettes were first seen in Japan in 2007.44 The popularity of menthol capsule cigarettes is growing internationally, particularly in Latin America, and have substantial appeal to young smokers and those experimenting with smoking.47 Between 2012 and 2014 preference for cigarettes featuring flavour capsules increased significantly in Australia, from 1% to 3% of all smokers, with 18–24 year olds being the most likely to prefer capsules at 4%. Smokers who preferred brands with capsules viewed their cigarettes as having more positive appeal and better taste when compared to traditional cigarettes.45 Menthol capsules are particularly popular among Australian teenagers, with more than half of past-month teen smokers reporting having smoked one of these products in a 2014 national survey.48 A qualitative study of Scottish smokers found that younger people (aged 16 to 35 years) frequently viewed capsule cigarettes as “novel, cool, innovative, fashionable and fun; something new that young people would be keen to experiment with”.44 p7 Capsule cigarettes showed less appeal among older smokers.

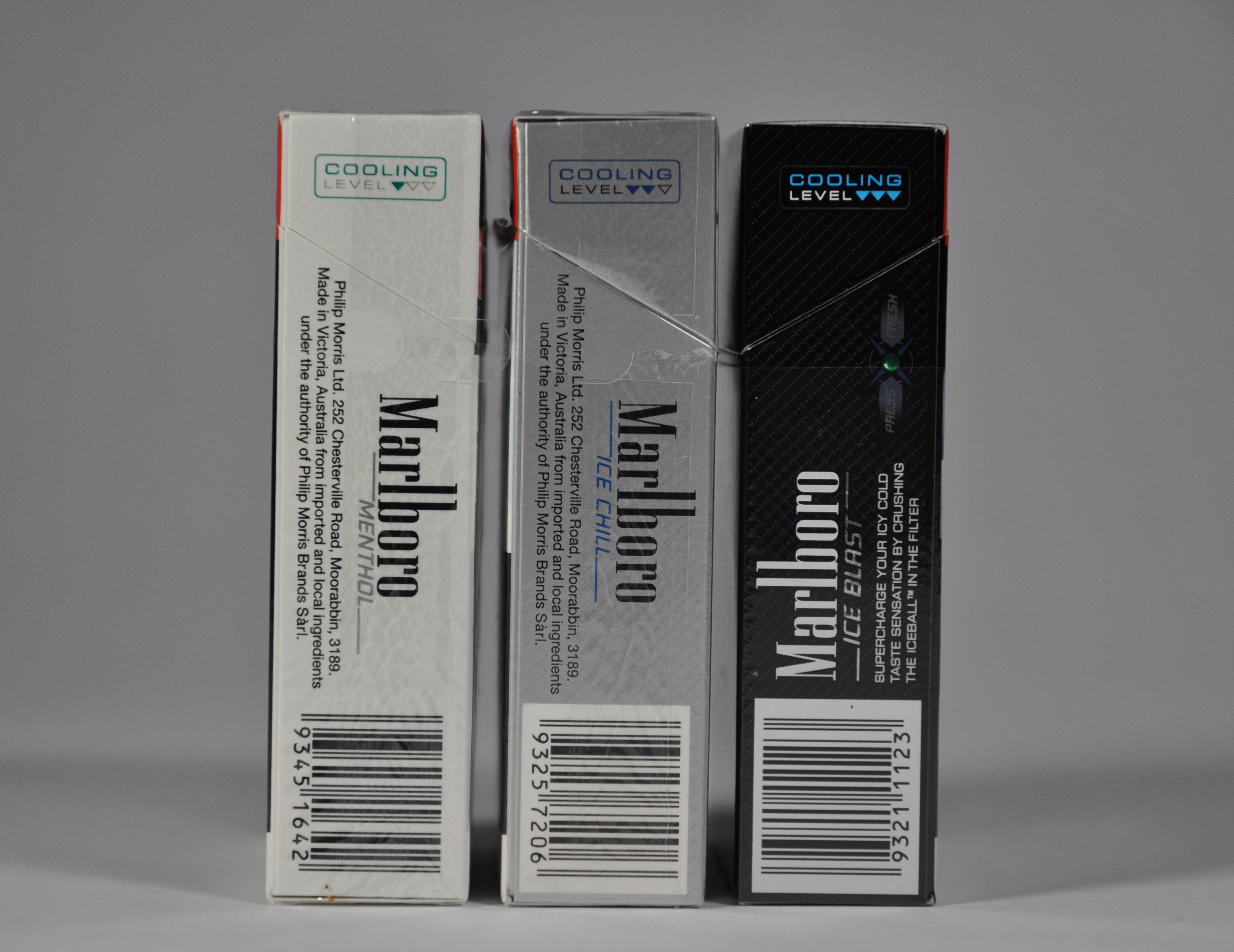

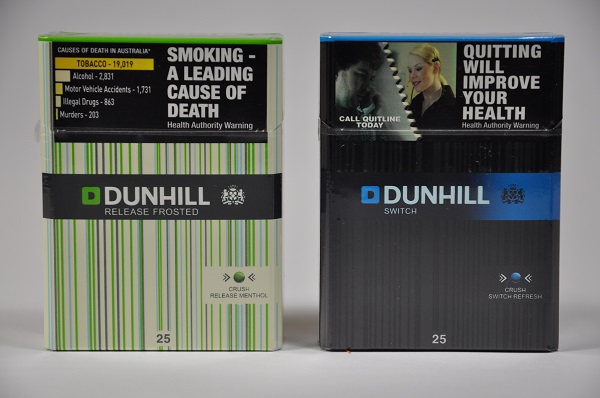

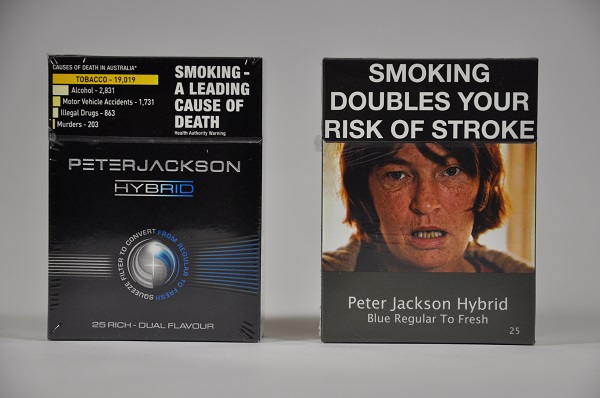

Menthol capsule packs often include design elements to communicate the capsule’s function and customisable flavour. Menthol capsule brands in the US have been observed to feature phrases such as “choose to refresh your taste” and “create your refreshing taste experience”49. Figure 10.6.24a shows Australian Dunhill menthol capsule products with capsule symbols and the instruction “Crush release menthol” (see also Figure 10.6.25). Figure 10.6.24b illustrates various international menthol capsule cigarette sticks with symbols on the filter indicating where the capsule is located. Following plain packaging, these design elements were banned in Australia. Philip Morris’ Peter Jackson Hybrid branded packs featured an image of a capsule with the instructions “Squeeze filter to convert from regular to fresh”, and the variant name Rich Dual Flavour, also featuring the colour blue in these design elements. After plain packaging, these same cigarettes were labelled Peter Jackson Hybrid Blue Regular to Fresh—see Figure 10.6.24c.

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

Source: Smith et al., 201640

Source: Scollo et al, 20158

Many major brand families include a menthol capsule variety, including product names such as Ice Blast, Summer Crush Rush, Switch, and Pop Refreshing Crushball. In 2017, dual capsule cigarettes (with two different flavoured capsules) were introduced to the Australian market—see Figure 10.6.25.

Source: Scollo et al. 201711

10.6.4.2 Flavoured roll-your-own and pipe tobacco

Existing restrictions target sweet and fruity flavours that appeal to children. However, other flavoured roll-your-own and pipe tobacco products continue to be available on the Australian market. These include coffee and many alcohol flavoured varieties, such as bourbon, whisky, rum, and wine.50 Flavoured cigarette papers for use with RYO tobacco are also available, including varieties such as bubblegum, watermelon, and choc-chip cookie dough.51

10.6.5 Organic, additive-free, and ‘green’ cigarettes and tobacco

A variety of ‘green’ (environmentally-friendly) and natural-sounding attributes have been claimed for particular tobacco products, responding to growing consumer awareness of environmental concerns. With no hint of irony, these include references to purity, naturalness and the lack of additives, as well as claims for the farming practices employed in the production of the leaf—such as allusions to organic growing conditions, reforestation programs, use of renewable energy sources such as wind power52 and ethical sourcing from farmers.53 This trend has been especially marked in the US,52 where consumer concerns have led to the marketing of organic, ‘100% additive free natural’ brands such as American Spirit54 and 1st-Nation.53 Figure 10.6.26 shows an advertisement for American Spirit that ran in US magazines in 2011 claiming to be ‘eco-friendly’ as well as ‘100% additive-free natural tobacco’, reflecting the growing consumer demand for green products.55 Growing demand for more biodegradable cigarette filter materials has also been noted in tobacco industry trade magazines.56

Source: Koch, 201155

There is also evidence that these types of descriptors tend to offer the consumer reassurance, since ‘natural’ commonly connotes beneficial attributes.52 Written disclaimers placed on these products to inform consumers that they are not safer cigarettes (see Figure 10.6.14 for an example) do not sufficiently correct misperceptions because they are largely ignored, distrusted, doubted, or simply not seen.57 Although some manufacturers are careful not to claim health attributes for their products,54 it is significant that US tobacco companies have sought to retain the right to use the descriptor ‘natural’ on their cigarettes sold outside the US.52 In 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration issued a warning letter to manufactures who included ‘natural’ and ‘additive free’ labels on their products stating that they constitute an authorised reduced harm claim.58 As of December 2016, no follow-up action had been taken. A 2016 US study found that the three sub-brands whose smokers were most likely to regard them as less harmful than other cigarettes were all currently marketed as natural or additive free (American Spirit varieties and Winston).59

At the time of writing no brands from the major tobacco companies operating in Australia claim to be organic or additive free, although at least two brands imported by smaller companies, Natural American Spirit and Manitou Organic cigarettes and RYO tobacco are available, as well as a small range of herbal cigarettes.50

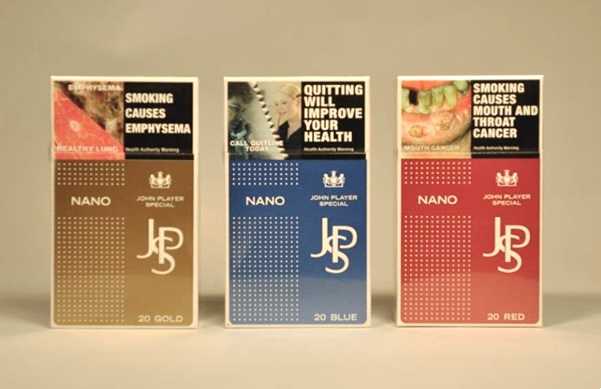

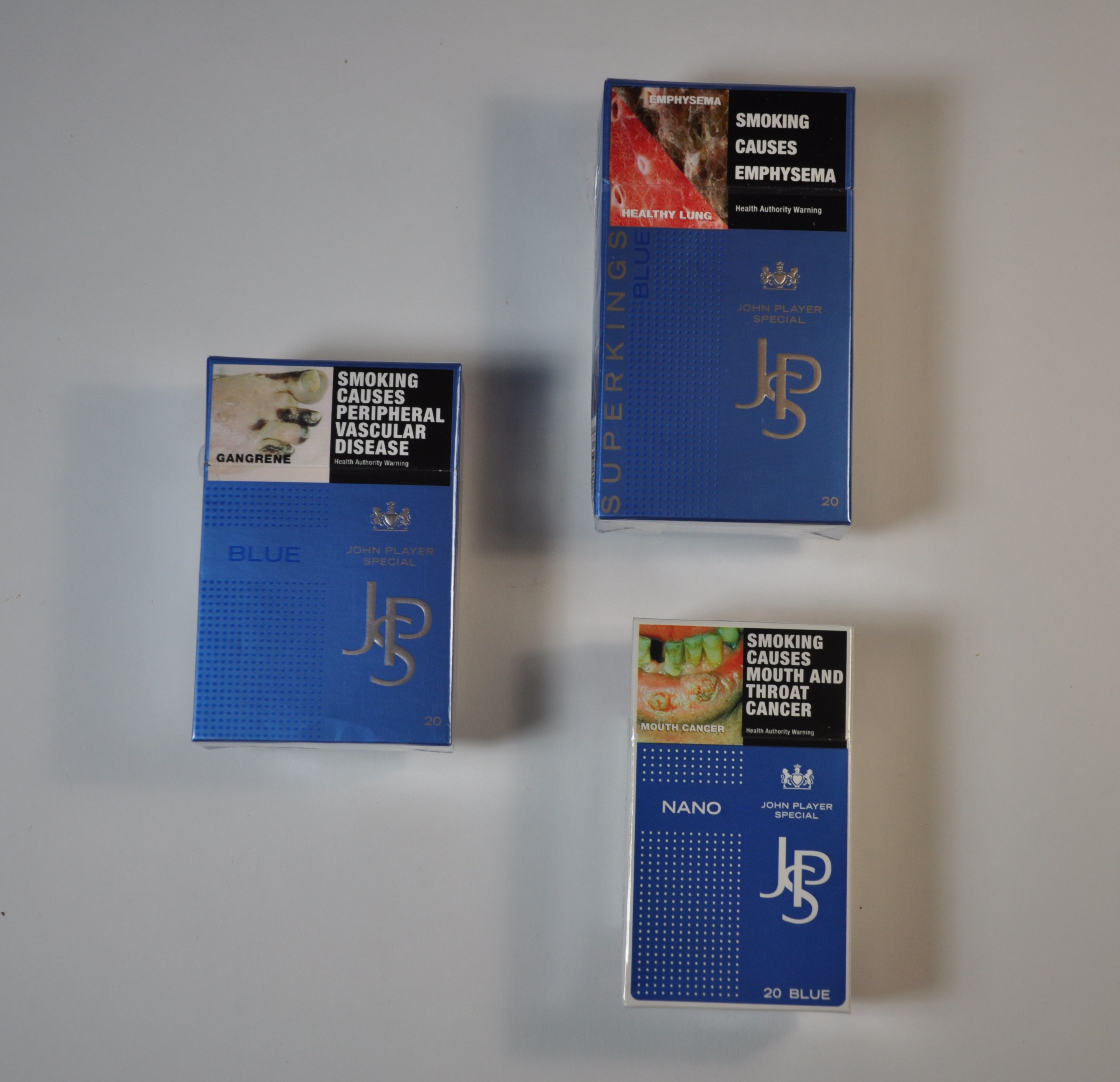

10.6.6 Slim, extra-long, and shorter cigarettes

In Australia, slim cigarettes are typically smaller in diameter than regular cigarettes and either extra-long (e.g. Vogue Superslims) or shorter than regular cigarettes (e.g. JPS Nano, Winfield Jets). Long thin tobacco products, such as the Vogue brand, sold in Australia have been found to have unique appeal, particularly among young females. In a Scottish study, young, female, non and occasional smokers, perceived slim cigarettes as the most appealing and pleasant tasting, and least harmful.60 Another Scottish study found that the slimmer diameters of these cigarettes communicated weaker tasting and less harmful looking cigarettes among 15 year olds across gender and socio-economic groups.61

Shorter slim products may be particularly appealing to young smokers. JPS Nano was introduced in Australia in early 2012 (shortly before plain packaging implementation), featuring a textured ‘grip pattern’ on the pack and sharing its name with the then-popular iPod Nano device—see Figure 10.6.27. This super-value brand was particularly cheap and prominently promoted on price boards in tobacco retailers,62 and was a key product in the rapidly growing JPS brand family.8 This very small 20s pack did not conform to the minimum pack dimensions established in the plain packaging regulations, and was replaced with 23s in December 2012. Perhaps due to the higher price-point of a 23s pack compared to 20s, JPS Nano lost popularity and was discontinued in early 2014.11

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

Limited opportunities to smoke due to the introduction of smoking restrictions in many environments has prompted the development of a shorter cigarette, which allows quicker smoking (seven puffs instead of the more usual 10) while still aiming to deliver a satisfying dose of nicotine. One company to cater for this market internationally is Philip Morris with Marlboro Intense, which has been launched in Turkey, and Marlboro Wides, a thicker but shorter than usual cigarette, innovatively packaged in a box with a flip-top opening from side to side instead of front to back.63 Conversely, extra-long or ‘superking’ cigarettes are typically the same diameter as regular cigarettes, but provide additional tobacco in a longer stick. For example, regular Horizon cigarettes contain 0.664 grams of tobacco, compared to 0.720 grams of tobacco in Horizon 93mm Long.64

10.6.7 Filter innovations

In addition to the introduction of flavour capsules in the cigarette filter (Section 10.6.4.1) and visual design elements included in the filter tip or tipping paper (Section 10.6.3), many tobacco products feature specialised or advanced filters. Tobacco companies have promoted cigarette filters in their advertising ever since health concerns about smoking arose in the 1950s, however, more recently innovative filters have been introduced in many markets.65 Charcoal filter cigarettes—long been available in Australia in the international brands Mild Seven (now discontinued) and Kent—were introduced under the Australian leading brand, Winfield in 2006. These new Winfield Charcoal Filter cigarettes were promoted in retail magazine advertisements as:

“A smooth start for the smooth choice…Not only does the Charcoal Filter reduce some the harsh taste in the smoke, providing a smooth smoking experience, the Winfield Charcoal Filter range gives your customers more choice.”

‘Smooth as', Australian Retail Tobacconist, 200666

The advertisement also highlighted increased profitability due to the higher recommended retail price of the Charcoal Filter range relative to regular Winfield cigarettes.

Tobacco industry trade magazines have noted the recent global rise in the market for specialty filters in the context of increasing packaging and promotion restrictions:

“As stricter regulation is enforced, specialty filters will be ever more important as a point of brand differentiation.”

Rossel, Tobacco Reporter 201767 (p44)

In 2015, British American Tobacco Australia and Philip Morris Australia began replacing their regular products offerings within many major brands with specialty filters. For example, the iconic brand Winfield introduced Winfield + Taste Flow Filter. These were not a brand extension—all regular Winfield products were phased out and replaced with the Taste Flow Filter range. Similar changes were made to the popular brands Alpine, Benson & Hedges, Dunhill, Longbeach, Peter Jackson, and Rothmans.11 Two types of filters have been introduced: recessed filters (labelled as Taste Flow Filter) and firm filters (labelled as Firmer Feel Filters or Firm Filter). In cigarettes with recessed filters, the filter tow is set back several millimetres, reportedly to provide “a different look” and “…create a smoother taste and shift the staining observed on the cigarette mouth end away from the consumer.”56 (p74)

Firm filters have the same appearance as regular filters but are much denser. According to a Philip Morris executive the UK, where the firm filters were launched on redesigned Marlboro packs in 2015, “firmer filters…offer quality you can feel, and a cleaner way to stub out your cigarettes”.68

A wide range of types of filters for rolling tobacco are also available. Australian retail trade magazines list product ranges from tobacco accessory suppliers including slim, ultra slim, and micro slim, charcoal, and charcoal slim.69

10.6.8 Product and packaging responses to plain packaging legislation: pre- and immediately post- implementation

Following the Australian government’s 2010 announcement of its intention to introduce plain packaging for tobacco products, numerous changes to the packaging and naming of tobacco products were observed. Other than reassurance messages, these responses continued in the months after plain packaging was implemented in December 2012. Reassurance messages were observed on the packs from several major brands, including banners on packs and pack inserts assuring consumers that despite the impending change in packaging, the taste and/or quality of their product would be unchanged—see Chapter 11, Section 11.10.10 for examples.

10.6.8.1 New brands, pack sizes, and brand extensions introduced prior to implementation of plain packaging

Many of the packaging and product trends described above were observed in high concentration in the period between the plain packaging announcement and implementation, particularly those aimed to convey value through the pack (Section 10.6.1). Where only one product had been available with ‘bonus’ cigarettes (Holiday 22s), these were increasingly introduced on predominantly budget brands. Similarly, many budget brands in very simple packaging were introduced during this period, including at least one super-value brand from each of the major three tobacco companies operating in Australia. These simple or ‘plain’ pack designs may have been predicted to fare better than many current brands after the transition to plain packaging—see Figure 10.6.2. Philip Morris introduced the exclusively named but very simply packaged Bond Street (an existing brand available for many years outside Australia) in a novel 26s pack size in February 2012. This provided an extra cigarette compared to the usual 25s and (being quite plain) was of a design that would have to change less dramatically than that of many other brightly coloured brands. British American Tobacco Australia's less elegant but 'to the point' Just Smokes was introduced in May 2012 priced well below almost every other brand on the market.8

Instead of introducing a new brand to the market, Imperial Tobacco continued to expand the range of products offered within the super-value JPS brand family. In 2009, the long-established John Player Special brand was re-badged as JPS in 2009 and sold only in packs of 25s. JPS Superkings 20s—extra-long cigarettes—were also introduced in early 2012. Several months later, the JPS product range expanded to include regular 20s and 25s, JPS Superkings 20s, and JPS Nano 20s,each available in several variants—see Figure 10.6.28. Figure 10.6.27 also shows that these Nano cigarettes were much smaller—both slimmer and shorter—than regular cigarettes, with technologically advanced-looking packaging to match the Nano name (invoking the then-popular iPod Nano device). A further sub-brand, JPS Duo, was noted from November 2012. This menthol capsule product just one month before the last date on which branded packages could be sold in Australia. Shortly after plain packaging implementation, a further brand extension JPS Ice was also introduced.

Source: Quit Victoria pack collection

Beyond the budget segment of the market, changes to the product offerings of several mainstream and premium brands were observed. These included additional menthol capsule products, extra-long cigarettes, and brand extensions with long, evocative product names (e.g. Peter Stuyvesant New York Blend, Marlboro Silver Fine Scent).8

10.6.8.2 Changes to product and variant names

With the removal of colours and other design elements from cigarette packs, tobacco companies instead used the product name to convey product information and associations. For example, Peter Jackson Hybrid branded packs featured an image of a capsule with the instructions “Squeeze filter to convert from regular to fresh”, and the variant name Rich Dual Flavour, with the colour blue featuring in these design elements. After plain packaging, these same cigarettes were labelled with the instructive variant Blue Regular to Fresh—see Figure 10.6.24c above. Philip Morris also altered the naming of Marlboro varieties following plain packaging. The variant name (e.g. Red, Gold), was incorporated into the brand name, so that instead of ‘ Red’ appearing as the variant name in smaller text under the brand name, ‘ Marlboro Red’ appeared in the larger brand font in a single line.8

As discussed in Section 10.6.2.1, cigarette variants (or ‘strengths’) have long-established associations with packaging colours. Following plain packaging, cigarette brands that used descriptive variant names (e.g. Dunhill Distinct, Dunhill Premier) incorporated the earlier pack colour into these variant names (Dunhill Distinct Blue, Dunhill Premier Red). Conversely, brands that did not have descriptive words in the pack, but may have relied on pack imagery and other design characteristics to convey positive brand associations, expanded their variant names. For example, Pall Mall Blue became Pall Mall Rich Blue, Holiday Gold became Holiday Sun Gold. Ahead of these changes, British American Tobacco Australia provided an information sheet to retailers describing the upcoming name changes to its products. This included the statement “new descriptors—the way your customers ask for it”.

These changes occurred despite the tobacco industry’s arguments that plain packaging would severely impede their ability to introduce and differentiate their products. Greenland observed that plain packaging presented no such restriction in the Australian market, having documented extensive and innovative changes to cigarette product offerings in the years immediately following plain packaging implementation.70,71

Related reading

Relevant news and research

A comprehensive compilation of news items and research published on this topic (Last updated April 2025)

Read more on this topic

Test your knowledge

References

1. Slade J. The pack as advertisement. Tobacco Control, 1997; 6(3):169-70. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/cgi/reprint/6/3/169.pdf

2. Wakefield M, Morley C, and Horan J. The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tobacco Control, 2002; 11(suppl. 1):i73-80. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/cgi/reprint/11/suppl_1/i73.pdf

3. Scheffels J. A difference that makes a difference: young adult smokers' accounts of cigarette brands and package design. Tobacco Control, 2008; 17:118-22. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18303087

4. Ford A. The packaging of tobacco products. Stirling: Centre for Tobacco Control Research, University of Stirling, 2012. Available from: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/prod_consump/groups/cr_common/@nre/@new/@pre/documents/generalcontent/cr_086687.pdf.

5. Moodie C and Hastings GB. Making the pack the hero, tobacco industry response to marketing restrictions in the UK: findings from a long-term audit. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 2009; 9(1):24-38. Available from: http://www.springerlink.com/content/r2116132350656k6/

6. Moodie C and Hastings G. Tobacco packaging as promotion. Tobacco Control, 2010; 19(2):168-70. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/19/2/168.short

7. Ford A, Moodie C, and Hastings G. The role of packaging for consumer products: understanding the move towards ‘plain’ tobacco packaging. Addiction Research and Theory, 2012; 20(4):339-47. Available from: http://informahealthcare.com/doi/abs/10.3109/16066359.2011.632700

8. Scollo M, Occleston J, Bayly M, Lindorff K, and Wakefield M. Tobacco product developments coinciding with the implementation of plain packaging in Australia. Tobacco Control, 2015; 24(e1):e116-22. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2014/04/30/tobaccocontrol-2013-051509.short

9. O'Leary C. Extra cigarette promo panned. The West Australian, 2013. Last update: Viewed 10/10/16. Available from: https://au.news.yahoo.com/thewest/wa/a/17966607/extra-cigarette-promo-panned/#page1

10. http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/tobacco-giant-shrinking-size-of-some-cigarette-packs-as-smokers-to-be-hit-with-another-tax-rise/news-story/535e6f0188faad2317a570620e6b7b26.

11. Scollo M, Bayly M, White S, Lindorff K, and Wakefield M. Tobacco product developments in the Australian post-plain packaging market to 2017. Tobacco Control, 2017; IN PRESS.

12. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Price lists. The Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2015; 95(Jul-Aug).

13. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Price lists. The Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2017; 101(Jan-Mar).

14. Greenland SJ. Cigarette brand variant portfolio strategy and the use of colour in a darkening market. Tobacco Control, 2015; 24:e65-e71. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/24/e1/e65

15. Squires R. Coles importing cheap cigarettes from Germany and selling them at discount prices. The Sunday Telegraph, 2010; 18 Jul. Available from: http://www.news.com.au/business/coles-importing-cheap-cigarettes-from-germany-and-selling-them-at-discount-prices/story-e6frfm1i-1225893467835

16. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Imperial Tobacco front page advertisement: "New look same taste". Australian Retail Tobacconist, 1997; 57(5):1.

17. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Imperical Tobacco front cover advertisement: "the dawn of a new look horizon". Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2004; 64(6):1.

18. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Imperial Tobacco advertisement: "Same great taste". Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2008; 70(3):3.

19. Hitchman SC, Calder R, Rooke C, and McNeill A. Small Retailers’ Tobacco Sales and Profit Margins in Two Disadvantaged Areas of England. AIMS Public Health, 2016; 3(1):110-5.

20. Wakefield M and Letcher T. My pack is cuter than your pack. Tobacco Control, 2002; 11:154-6. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/cgi/content/abstract/11/2/154

21. Dunhill gets smoother. The Grocer, 2005; 18 Jun. Available from: http://www.thegrocer.co.uk/topics/dunhill-gets-smoother/102820.articlehttp://www.forecourttrader.co.uk/news/fullstory.php/aid/2726/Still_burning_bright.html

22. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Price lists-cigarettes. The Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2012; 84(no. 6 May-July):1-2.

23. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Price lists-cigarettes. The Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2011; 80(no. 1 Feb-Mar-Apr):1-2.

24. Still burning bright. The Forecourt Trader, 2009; January:52. Available from: http://www.forecourttrader.co.uk/news/fullstory.php/aid/2726/Still_burning_bright.html

25. Chapman S. Australia: British American Tobacco 'addresses' youth smoking. Tobacco Control, 2007; 16(1):2-a-3. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/cgi/reprint/16/1/2-a

26. Anon. Cigarette split pack defeated. The Daily Telegraph, 2006; 18 Nov. Available from: http://global.factiva.com.ezproxy.library.usyd.edu.au/ha/default.aspx

27. Borland R, Savvas S, Sharkie F, and Moore K. The impact of structural packaging design on young adult smokers' perceptions of tobacco products. Tobacco Control, 2012. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2011/12/12/tobaccocontrol-2011-050078.abstract

28. Swanson MG. Australia: health warnings canned. Tobacco Control, 2006; 15(3):151. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/cgi/content/extract/15/3/151?rss=1

29. Gantry shake up. The Forecourt Trader, 2006; 2 May:52. Available from: http://www.forecourttrader.co.uk/news/archivestory.php/aid/1254/Gantry_shake_up.html

30. In brief. Off License News, 2008; 2 May. Available from: http://www.offlicencenews.co.uk/news/archivestory.php/aid/8438/In_brief.html

31. Dutt IA. Paresh Maity designs for ITC, upsets anti-smoking lobby. Business Standard, 2012; Aug 30. Available from: http://www.business-standard.com/india/news/paresh-maity-designs-for-itc-upsets-anti-smoking-lobby/484871

32. Haché T. News analysis: CANADA: BAT'S “GREENWASH”. Tobacco Control, 2009; 18(4):252-5. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/tobaccocontrol/18/4/252.full.pdf

33. Bansal-Travers M, Hammond D, Smith P, and Cummings K. The impact of cigarette pack design, descriptors, and warning labels on risk perception in the US. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2011; 40(6):674–82. Available from: http://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797%2811%2900166-8/fulltext

34. Bansal-Travers M, O'Connor R, Fix B, and Cummings K. What do cigarette pack colors communicate to smokers in the US? American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2011; 40(6):683–9. Available from: http://www.ajpmonline.org/article/S0749-3797%2811%2900161-9/fulltext

35. Lempert L and Glantz S. Packaging colour research by tobacco companies: the pack as a product characteristic. Tobacco Control, 2016. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2016/06/02/tobaccocontrol-2015-052656.abstract

36. Dewhirst T. Into the black: Marlboro brand architecture, packaging and marketing communication of relative harm. Tobacco Control, 2017. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/tobaccocontrol/early/2017/04/20/tobaccocontrol-2016-053547.full.pdf

37. King B and Borland R. What was 'light' and 'mild' is now 'smooth' and 'fine': new labelling of Australian cigarettes. Tobacco Control, 2005; 14(3):214–5. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/14/3/214

38. Rommel C. The final warnings. World Tobacco, 2006; (203):2.

39. British American Tobacco Australia. Strengthening our sustainability approach: Australian Packaging Covenant Annual Report 2015. Sydney, Australia: BATA, 2016. Available from: http://www.bata.com.au/group/sites/bat_9rnflh.nsf/vwPagesWebLive/DO9RNMR2/$FILE/medMDAD785Y.pdf?openelement.

40. Smith KC, Washington C, Welding K, Kroart L, Osho A, et al. Cigarette stick as valuable communicative real estate: a content analysis of cigarettes from 14 low-income and middle-income countries. Tobacco Control, 2016. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27534777

41. O’Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, Cummings KM, Hammond D, Thrasher JF, et al. Filter presence and tipping paper color influence consumer perceptions of cigarettes. BMC Public Health, 2015; 15(1):1279. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2643-z

42. Ahijevych K and Garrett B. Menthol pharmacology and its potential impact on cigarette smoking behavior. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2004; 6(suppl.1):i17-28. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14982706

43. Robinson J. Man slapped with £575 fine for dropping cigarette end outside place of work. Lancashire Telegraph, 2015. Available from: http://www.lancashiretelegraph.co.uk/news/11775586.Man_slapped_with___575_fine_for_dropping_cigarette_end_outside_place_of_work/

44. Moodie C, Ford A, Dobbie F, Thrasher J, McKell J, et al. The power of product innovation: Smokers’ perceptions of capsule cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2017; Online first: 30 August 2017. Available from: https://academic-oup-com.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au/ntr/article/doi/10.1093/ntr/ntx195/4098286/The-power-of-product-innovation-Smokers

45. Thrasher JF, Abad-Vivero EN, Moodie C, O'Connor RJ, Hammond D, et al. Cigarette brands with flavour capsules in the filter: trends in use and brand perceptions among smokers in the USA, Mexico and Australia, 2012-2014. Tobacco Control, 2015. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25918129

46. Rossel S. Fit to burst. 2017. Last update: Viewed Available from: http://www.tobaccoreporter.com/2017/01/fit-to-burst/.

47. Thrasher JF, Islam F, Barnoya J, Mejia R, Valenzuela MT, et al. Market share for flavour capsule cigarettes is quickly growing, especially in Latin America. Tobacco Control, 2016. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27329114

48. White V and Williams T. Australian secondary school students' use of tobacco in 2014. Melbourne: Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, Cancer Council Victoria, 2015. Available from: http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/Publishing.nsf/content/school11.

49. Schwartz R, Chaiton M, Borland T, and Diemert L. Tobacco industry tactics in preparing for menthol ban. Tobacco Control, 2017. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/tobaccocontrol/early/2017/09/08/tobaccocontrol-2017-053910.full.pdf

50. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Price lists. The Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2016; 99(Jul-Sep).

51. http://www.beefysbongs.com.au/rolling-papers/flavoured-papers/.

52. McDaniel PA and Malone RE. 'I always thought they were all pure tobacco': American smokers' perceptions of 'natural' cigarettes and tobacco industry advertising strategies. Tobacco Control, 2007; 16(6):e7. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/cgi/content/abstract/16/6/e7

53. Am Trading. Corporate website. Akwesasne, New York: Amtrading, 2008. Last update: Viewed Available from: http://www.amtrading.us/main.html.

54. Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company. Corporate website. Winston-Salem, North Carolina: Reynolds American Inc, 2008. Last update: Viewed Available from: http://www.nascigs.com/.

55. Koch W. Eco-friendly cigarette ads make tobacco foes fume. USA Today, 2011; 26 Jul. Available from: http://www.usatoday.com/money/advertising/2011-07-26-green-cigarette-ads_n.htm

56. Rossel S. Focus on the filter. 2016. Last update: Viewed Available from: http://www.tobaccoreporter.com/2016/08/focus-on-the-filter/.

57. Byron MJ, Baig SA, Moracco KE, and Brewer NT. Adolescents’ and adults’ perceptions of ‘natural’, ‘organic’ and ‘additive-free’ cigarettes, and the required disclaimers. Tobacco Control, 2016; 25(5):517-20. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/25/5/517.abstract

58. No authors listed. FDA issues warning letters to "natural" tobacco makers, in Yahoo! News/AP 2015. Available from: https://uk.finance.yahoo.com/news/fda-issues-warning-letters-natural-154358972.html.

59. Leas EC, Ayers JW, Strong DR, and Pierce JP. Which cigarettes do Americans think are safer? A population-based analysis with wave 1 of the PATH study. Tobacco Control, 2016. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27742918

60. Moodie C, Ford A, Mackintosh A, and Purves R. Are all cigarettes just the same? Female’s perceptions of slim, coloured, aromatized and capsule cigarettes. Health Education Research, 2015; 30(1):1-12. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/her/cyu063

61. Ford A, Moodie C, MacKintosh AM, and Hastings G. Adolescent perceptions of cigarette appearance. European Journal of Public Health, 2014; 24(3):464-8. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt161

62. Scollo M, Bayly M, and Wakefield M. The advertised price of cigarette packs in retail outlets across Australia before and after the implementation of plain packaging: a repeated measures observational study. Tobacco Control, 2015; 24(Suppl 2):ii82-ii9. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/24/Suppl_2/ii82.full

63. O'Connell V. Philip Morris readies aggressive global push. The Wall Street Journal Online, 2008; 29 Jan. Available from: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB120156034185223519.html?mod=hpp_us_pageone

64. Imperial Tobacco Australia Limited. Australia Ingredients Report: By-Brand Variant Ingredients List For Reporting Period 2nd March 2015 to 1st March 2016. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government, 2016. Available from: www.health.gov.au/internet/main/...nsf/.../Imperial-Tobacco-Australia-Limited.pdf.

65. Czoli CD and Hammond D. Cigarette Packaging: Youth Perceptions of “Natural” Cigarettes, Filter References, and Contraband Tobacco. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 2014; 54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.016

66. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Winfield Charcoal Filter advertisement: Smooth as. Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2006; 66(8):8-9.

67. Rossel S. Ready to bloom. 2017. Last update: Viewed Available from: http://www.tobaccoreporter.com/2017/03/ready-to-bloom/.

68. No author listed. Philip Morris' plain Marlboro packaging emerges in UK. 2015. Last update: Viewed 21/08/2017. Available from: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/organic-tobacco-market-roll-your-own-tobacco-segment-anticipated-to-register-significant-cagr-over-the-forecast-period-global-industry-analysis-and-opportunity-assessment-2016-2026-300426528.html

69. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Price lists. The Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2013; 89(Oct-Nov-Dec).

70. Greenland S, Johnson L, and Seifi S. Tobacco manufacturer brand strategy following plain packaging in Australia: implications for social responsibility and policy. Social Responsibility Journal, 2016; 12(2):321-34. Available from: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/SRJ-09-2015-0127

71. Greenland SJ. The Australian experience following plain packaging: the impact on tobacco branding. Addiction, 2016; Online first 24 August 2016.