The term e-cigarettes is used in chapter 18 to refer to products that are used that simulate smoking by heating a non-tobacco e-liquid to form aerosol emissions. This is distinct from heated products (heat-not-burn) which heat a tobacco product to produce emissions (described in InDepth 18B). The nicotine used in e-cigarettes, however, is usually purified from tobacco plants.

18.1.1 E-cigarette product development

18.1.1.1 E-cigarette design and components

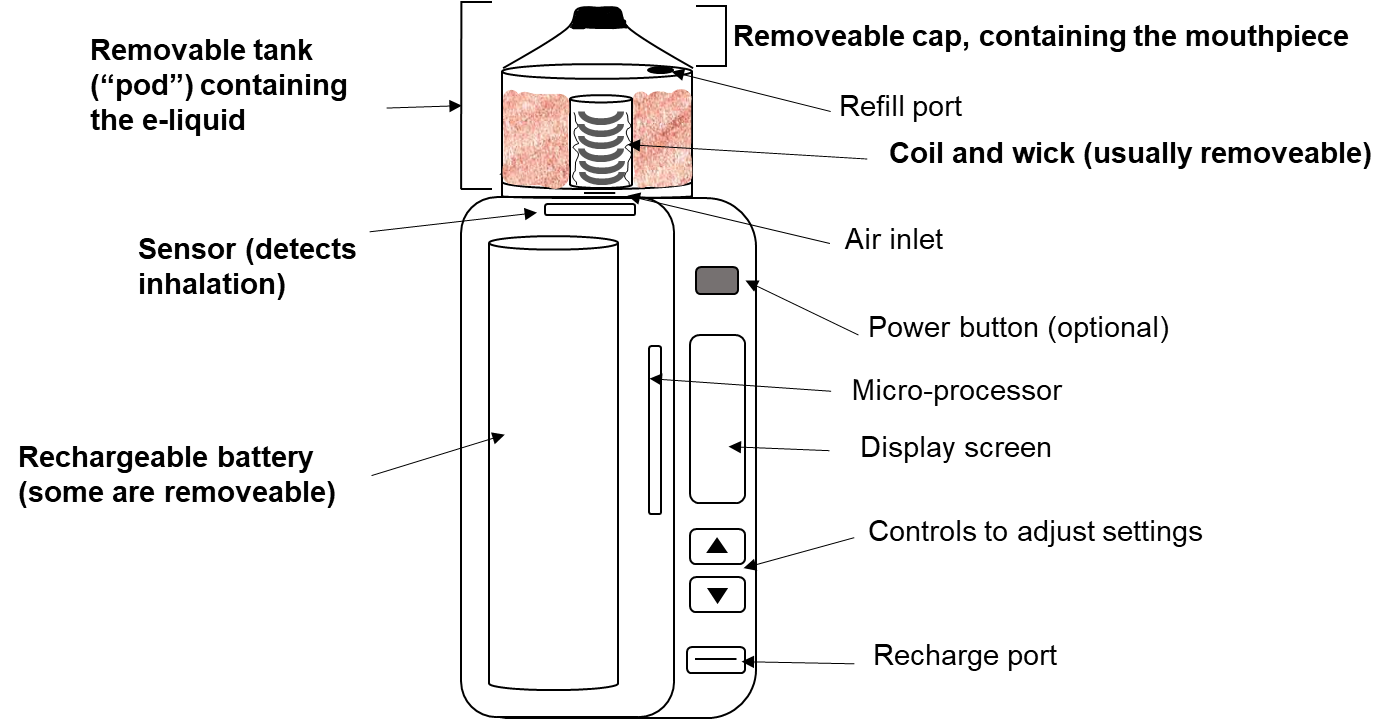

Most E-cigarettes contain common components such as a battery, a heating element, an e-liquid storage tank, a sensor to detect inhalation and a mouthpiece (shown in Figure 18.1.1). 1-3 During use, the sensor detects ‘draw’ (inhalation via the mouthpiece) triggering activation of the device. The battery supplies the power to the heating element as well as a microprocessor, screen and control buttons, if present. Power from the battery heats the coil in the heating element. E-liquid, which may be held next to the coil by a wick, is heated by the hot coil to form an aerosol. This aerosol accumulates and is then inhaled through the mouthpiece (‘drip tip’). The aerosol is frequently erroneously referred to as ‘vapour’ (see Section 18.5.1 for more details).

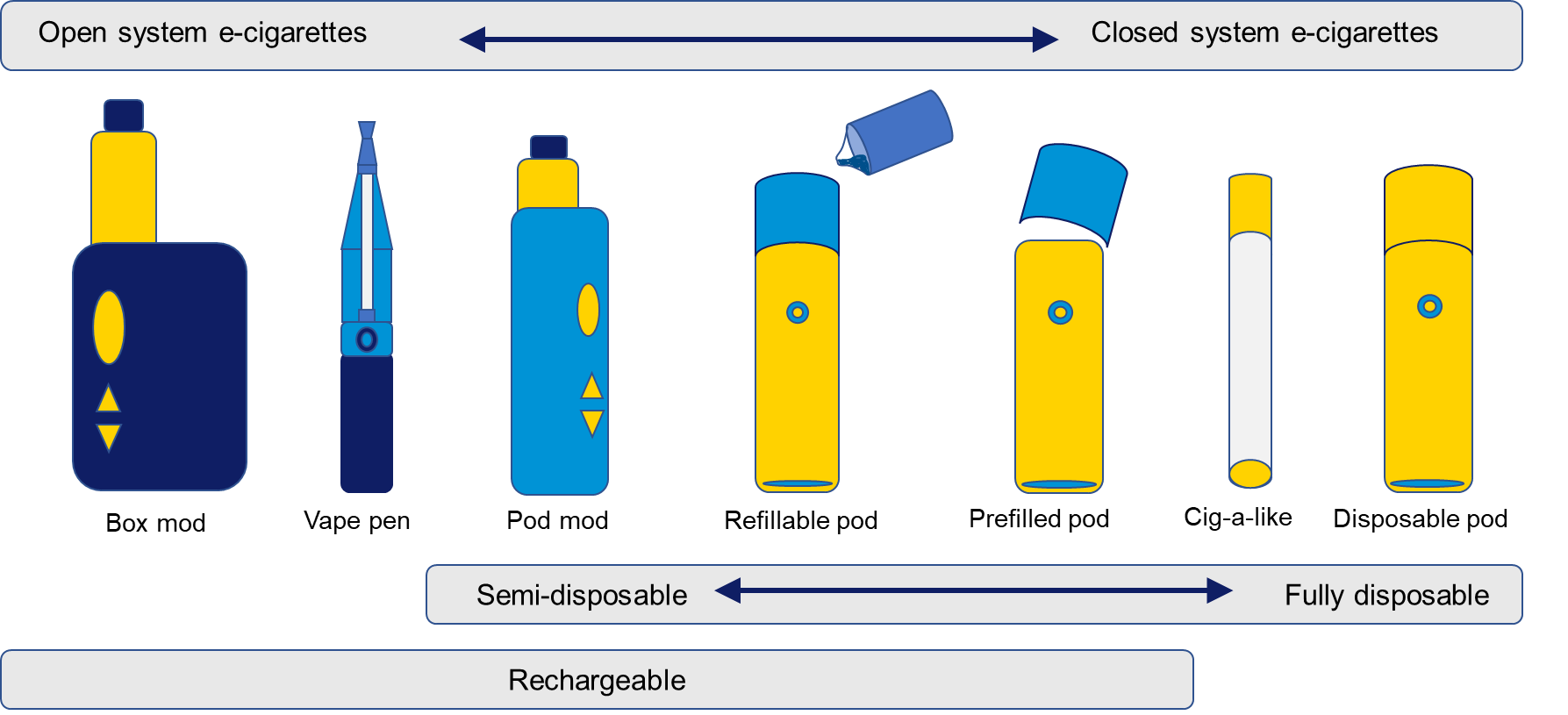

A variety of e-cigarette designs are described in Figure 18.1.2 and in more detail in Section 18.1.1.2. Some are fully disposable, some are reusable, while others have parts that regularly need replacing.

Figure 18.1.1 Components of a typical e-cigarette, based on the ‘mod pod’ design.

E-cigarette batteries

All e-cigarettes contain batteries, many of which are rechargeable. Most of the batteries found in e-cigarettes are rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. Fully disposable devices do not allow for battery recharging; these devices are used until either the battery is flat or the e-liquid runs out. Regardless, fully disposable devices often contain lithium-ion batteries, even though they will not be recharged. Some devices allow for the batteries to be removed and replaced. Battery explosions, fires and burns are described in Section 18.4.1.

Heating elements

All e-cigarettes contain heating elements, sometimes known as ‘atomisers’. These contain a heating coil that may consist of nickel, chromium and iron. 5 Some heating devices contain wicks that draws e-liquid into the space around the coil. Wicks may be made from fiberglass, cotton, silica or metal fibres. 4 , 5 Alternatively, the coil is embedded in ceramic with holes to let in the e-liquid. 5 Heating elements are in direct contact with the e-liquid and the aerosol produced by the device. 5 Upon heating, coil temperatures typically reach between 200°C and 350°C. 4

In non-disposable or semi-disposable devices, the heating elements need replacing at regular intervals as the coil becomes soiled or degraded, or the wick is degraded. In many devices, the heating element is fixed to the tank (‘pod’) and are disposed of and replaced with the tank. E-cigarette users will typically replace the coil once the flavour is affected, such as tasting ‘burnt’.

E-liquid tanks

Many e-cigarette devices are refillable, known as open systems. They are refilled with off-the-shelf or custom-mixed e-liquids. Some devices have glass tanks that can be cleaned and reused. Closed system refers to fully disposable e-cigarettes, which called not be opened or refilled.

Some e-cigarettes have plastic disposable tanks, known as ‘pods’, which are replaced with prefilled tanks once they are empty. Confusingly, the entire device may also referred to as a ‘pod’. More recently, devices have entered the market containing plastic tanks that can be refilled but not washed, and so need replacing once dirty. These devices are designated as semi-disposable in Figure 18.1.2 given they consist of a mix of non-disposable and disposable parts.

Modification of the user experience

Some varieties of e-cigarettes allow modification of the user experience by controlling the voltage, temperature and airflow. This allows selection of the amount of aerosol produced and the nicotine concentration. 6 Control buttons and screens for this purpose are usually present on the non-disposable parts of the device, often called the ‘mod’. Individual user behaviour, such as the length, depth, and frequency of puffs might also affect nicotine intake. 7 More information on modes of use can be found in Section 18.5.4.

E-liquids

A wide variety of e-liquids are available for refilling e-cigarettes. In Australia, the labelling of these liquids is a poor indicator of the contents of the bottle. Nicotine is often present when not listed or labelled as ‘nicotine free’. 8 The contents of e-liquids are described in Section 18.5.3. Some e-liquids contain nicotine salts— mixtures containing acids that cause the nicotine to become protonated. In the case of e-liquids, this is believed to allow a higher concentration of nicotine without the harsh taste expected of this concentration. See Sections 18.5.3 and 12.4.3.1 for more information about free-base nicotine versus nicotine salts.

18.1.1.2 E-cigarette product varieties and development

Although the design of an electronic cigarette was first patented in the USA in 1965, 9 it was not until 2003 that the first commercialised e-cigarette product was developed in China. 10 Since this time, e-cigarette design has undergone considerable innovation, resulting in the availability of a wide variety of devices with differing functionality. Distinct product types have entered the market sequentially and are often described as generations, as summarised in Figure 18.1.2 and below. 11

First generation— cig-a-likes

Original cig-a-likes, invented in 2003, 1 were fully disposable, closed systems that resembled cigarettes. They could not be refilled or recharged and there were no modifications of power or airflow available. Cig-a-likes on the market today still resemble cigarettes, but often have features such as rechargeable batteries and replaceable tanks, making them more like pods, described below.

Second generation—vape pens

Vape pens, named for their pen-like shape, entered the international market before 2010. They were open systems that allowed for refill with e-liquids and batteries could be recharged or replaced. Vape pens were also more colourful and stylish than cig-a-likes. Today’s vape pens have improved functionality, allowing users to modify their experience, more like pod mods (described below).

Third generation— box-mods

Box-mods, are large, rechargeable, refillable e-cigarettes with a highly customisable user experience. They are said to have entered the international market by 2010. 12 They are marketed to experienced user who wishes to modify use conditions and is prepared to replace and clean various parts of the device. They are not described as disposable, but the coils need replacing regularly, and they have other removable parts like batteries and tanks that could be switched out as part of customisation. They contain relatively large glass tanks that are cleanable and do not need replacing, but can be detached and replaced if desired.

Box mod use can be customised by; 1. removing and inserted different parts (batteries, coils and tanks), 2. using different types of e-liquids, 3. changing settings on the device to control power use, desired temperature and airflow, and 4. by the inhalation topography of the user.

Fourth generation— pods

Pods are marketed to new e-cigarette users due to their ease of use and the lack of maintenance required. They were also smaller and sleeker than box mods, and therefore considered more stylish. There is a broad range of different pods available with differing features.

Fully disposable pods are prefilled, closed devices with non-chargeable batteries. They can be used until the battery runs flat or the e-liquids runs out. These pods are often advertised as having thousands or many thousands of puffs. They usually contain few or no options for modification of the user experience.

Pods are also available with the ability to replace the disposable tank with a pre-filled tank. This also contains the coil, meaning that the coils on these semi-disposable devices do not need to be replaced separately. These devices are usually disposed of once the battery no longer performs well after multiple recharges.

Refillable pods are also available, which have detachable plastic tanks that can be filled with an off-the-shelf or custom-made e-liquid. This allows the user a greater choice of e-liquids as well as reducing the need for cleaning the tank, as is necessary for box-mods. Some pod devices can be attached to either prefilled or refillable tanks.

Pods may be used with e-liquids containing nicotine salts, whereas box mods are not considered appropriate for nicotine salts. An Australian study has shown that disposable devices contained higher concentrations of nicotine and mostly nicotine salts, whereas e-liquids sold separately as refills contained lower concentrations of nicotine and were mostly free-base nicotine. 13 See Section 18.5.3.1 for a description of nicotine salts in e-liquids.

Pod mods

Pod mods are the most recent innovation to enter the market. They share features of box mods, in that they have screens and controls to modify the user experience, as well as pods, in that they have detachable but refillable plastic tanks. These devices are best described as open, rechargeable and semi-disposable, due to the regular replacement of the coil and plastic tank. They therefore combine the functionality and modifiability of the box mod with the sleeker design and lower maintenance requirements of the pods.

18.1.2 The e-cigarette market

Thank you to the University of Bath’s Tobacco Tactics website 14 for compiling much of the information used in section 18.1.2.

18.1.2.1 Size of the e-cigarette market

A recent study estimated that in 2019, 23% of people across North America, Europe, Asia, and Oceania had ever tried e-cigarettes, and 11% were current users 15 (see Section 18.3 for detailed prevalence figures), with almost all (90%) e-cigarette products sold globally made in China. 16 Between 2014 and 2018 the value of the global e-cigarette market more than doubled from US$6.8 billion to over US$15.5 billion, and by 2021, it had increased to almost US$22.8 billion. North America is the largest e-cigarette market (US$7.8 billion in 2021), followed by Western Europe (US$6.5 billion in 2021). Within Western Europe, the e-cigarette market in the UK was worth more than US$2.9 billion in 2021. 14

The number of e-cigarette units, e-liquids and prefilled tanks sold in Australia is essentially unknown. There are no data available to predict the proportion of unit sales that were disposable, non-disposable or semi-disposable products.

A US study estimated that total e-cigarette unit sales increased from 7.7 million per 4-week period in September 2014 to 17.1 million by May 2020. Fully disposable e-cigarette sales now dominate the market in the US. The unit share of prefilled tanks decreased from 75.2% in January 2020 to 48% in December 2022 whereas disposable e-cigarette unit sales increased from 24.7% to 51.8% of total sales over the same time period. 17 Sales of high nicotine-strength e-cigarettes are now also dominant in the US market. In March 2022, the majority of total unit (80.9%) and dollar (79.5%) sales were for products containing ≥5% nicotine strength. Disposable e-cigarettes and prefilled cartridges all increased in nicotine strength between 2017 and 2022, with most disposable e-cigarettes and prefilled cartridges for sale in 2022 having nicotine strength ≥5%. 18

18.1.2.2 Independent e-cigarette companies

Historically, the e-cigarette market was highly fragmented and largely dominated by small start-up companies. 14 NJOY—a company independent of the tobacco industry—was the unrivalled market leader in 2012, but had filed for bankruptcy by the end of 2016. 11 In the US, British American Tobacco sales surged in 2014 and led into 2017. 19 However, by the end of 2017, JUUL (a sleek, portable e-cigarette that resembles a USB flash drive made by JUUL Labs) rapidly became the largest retail e-cigarette brand in the US, 19 and substantially increased sales of the entire e-cigarette category. 20 In 2018, JUUL accounted for more than two-thirds of the US e-cigarette market. 21 In December 2018, it was announced Altria was buying a 35 percent stake in Juul 22 (see 18.1.3, below). However, regulatory challenges, especially in the US, have led to JUUL’s share of the market declining since 2020. Since 2017, Chinese manufacturer RELX Technology has nearly doubled its yearly share of the global market to 9% in 2021, giving it the third largest share of any company, after BAT and JUUL. 14 EVO Brands—which manufactures Puff Bars—had the next largest share after RELX in 2021, with 1.7% of the global market. 14

18.1. 2.3 Tobacco industry investment in e-cigarettes

In response to declining smoking prevalence, transnational tobacco companies have increasingly diversified their product lines to include ‘reduced harm’ alternative nicotine products. Some have questioned the ethics and motives of such diversification, with tobacco companies profiting from smokers, new nicotine users, and would-be quitters. 23

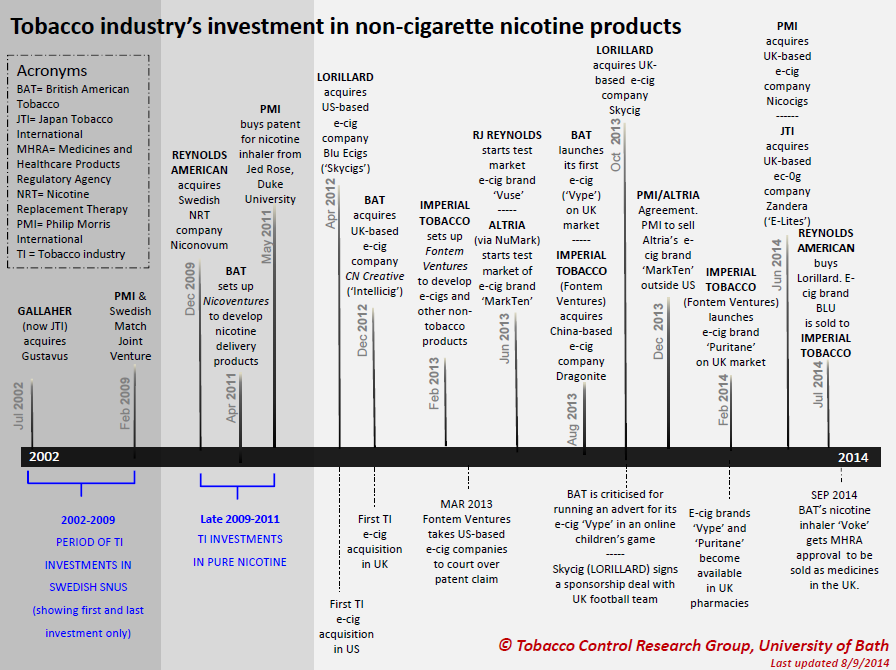

Although initially slow to enter the market, the major international tobacco companies have invested heavily in e-cigarettes, and tobacco companies now own many of the top e-cigarette brands. 11 Figure 18.1.3 below, shows the tobacco industry’s initial entry into the e-cigarette market:

Figure 18.1.3 Tobacco industry investment in non-cigarette nicotine products

Source: Tobacco Control Research Group, Tobacco industry investment in non-cigarette nicotine products. TobaccoTactics.org, University of Bath.

Acquisitions and investments by the tobacco industry include the following:

- British American Tobacco (BAT) acquired CN Creative in 2012, a start-up that developed the ‘Vype’ e-cigarette. BAT went on to launch Vype in the UK in 2013, and in France, Germany, Italy, Poland and Colombia in 2015. In 2015, BAT acquired the e-cigarette brands Ten Motives in the UK and CHIC in Poland. 14 In 2017, BAT acquired Reynolds American for $49 billion, and reportedly expressed particular interest in the company's next generation products, including its best-selling US e-cigarette brand, Vuse. 23 In 2018, BAT launched a new vaping device in the UK—the Vype iSwitch– which was reportedly designed to delivered nicotine to the user in a more efficient manner. 24 In subsequent years BAT continued to acquire more independent e-cigarette companies, and developed a range of products under the Vype and Vuse brands. In 2020, BAT began consolidating the two brands as Vuse. In 2022 it launched a disposable product, Vuse Go. 14

- Lorillard, the third-largest cigarette manufacturer in the US, acquired the e-cigarette company blu eCigs for a reported $135 million in 2012. It also acquired Skycig, a leading brand of e-cigarettes in Britain, for $48.5 million, allowing it to enter the UK market. Skycig then became blu eCigs in May 2014, with the support of a £20 million marketing campaign. When RJ Reynolds acquired Lorillard in 2014, Imperial Tobacco purchased its blu line to avoid antitrust concerns that RJ Reynolds owning both Vuse and blu would give it an unfair advantage in the market. 14

- Japan Tobacco International (JTI) entered the e-cigarette market in 2011 by investing in the start-up Ploom Inc. (now known as JUUL Labs). In 2014 it acquired UK e-cigarette brand E-lites from previous owner Zandera. E-Lites was one of the leading e-cigarette brands in the UK, and the first to be available in the four biggest supermarkets. In 2015, it acquired US company Logic, and from 2016, E-Lites was rebranded as Logic. JTI has since focused on marketing its Logic e-cigarettes. 14

- Fontem Ventures (a subsidiary of Imperial Tobacco) acquired Dragonite in August 2013, which was previously owned by the Chinese pharmacist who invented the modern e-cigarette. In early 2014, Imperial presented its own e-cigarette called Puritane. Imperial also purchased the blu e-cigs line as part of the merger between Reynolds and Lorillard in 2014. In February 2015, Imperial announced the launch of its new e-cigarette, Jai, in France and Italy. 14

- Philip Morris International (PMI) announced in December 2013 that it was joining with Altria to market e-cigarettes and other ‘reduced risk’ tobacco products. PMI gained the right to exclusively sell Altria's e-cigarettes outside the US. In 2014, PMI acquired UK-based Nicocigs, the owner of the Nicolites brand, claiming that it would provide immediate entry to the UK market for these and any other e-cigarette products. 14 In 2018, PMI launched its own e-cigarette, the IQOS Mesh, which heats disposable sealed pods. 25 Mesh was relaunched as VEEV in 2020. In 2022, PMI launched a disposable e-cigarette called VEEBA. 14 However, PMI has focused more heavily on the heated tobacco product market—see InDepth 18B.

- Altria, which owns Philip Morris USA and controls about one half of all cartons sold in America, launched its e-cigarette ‘MarkTen’ in 2013. In 2014, Altria also acquired the e-cigarette manufacturer Green Smoke. 14 In late 2018, Altria announced it had invested close to $13 billion in order to acquire a 35% stake in JUUL Labs Inc. By June 2022, this investment was reported to be worth only US$450 million. 14

Despite investments by tobacco companies, independent e-cigarette companies have maintained a larger share of the global market. However, this has fluctuated over time, from over 80% in 2014–2016 down to about 56% in 2019. The market share of independent companies has begun rising again in the past few years, probably due to the withdrawal of JUUL from some markets. 14

18.1.2.4 Lobbying for favourable regulation

The market size of e-cigarettes can be affected by national regulations on the sale and use of the products. Countries with the most restrictive policies tend to have lower e-cigarette use; 26 however poor enforcement of even very tight regulations—as is the case in Australia 27 (see Section 18.13)—as well as industry influence and lobbying has led to rapidly increasing and widespread use, particularly among young people.

In Australia, major tobacco companies including Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco have reportedly lobbied federal government MPs—both directly and indirectly—to overturn the current ban on the retail sale of e-cigarettes containing nicotine. Lobbyists from tobacco companies have reportedly met with federal MPs who have advocated federal enquiries into e-cigarettes and who support widespread availability of the products. Tobacco companies have also donated directly to the National Party and the Liberal National Party (see Section 10A.7), and have indirectly donated to sympathetic groups such as the Australian Retailers Association in order to lobby for the deregulation of e-cigarettes. 28 , 29 The Australian Tobacco Harm Reduction Association (ATHRA), which has led lobbying efforts to legalise nicotine e-cigarettes, reportedly accepted initial funding from e-cigarette companies 30 as well as funding from an overseas group that had received money from tobacco companies. 31

Relevant news and research

A comprehensive compilation of news items and research published on this topic

Read more on this topic

References

1. Britannica. E-cigarette. 2023. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/e-cigarette

2. Drag X/Drag S user manual. Available from: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/61e5df56a33d334ec9ffacb3/t/62180fa43a440c531167cb2c/1645744039330/DRAG+S+USER+MANUAL.pdf.

3. Vaporesso Target 80 60W Pod Mod kit User Manual. 2022. Available from: https://manuals.plus/vaporesso/target-80-60w-pod-mod-kit-manual#ixzz88eL3Q5C1.

4. Dibaji SAR, Guha S, Arab A, Murray BT, and Myers MR. Accuracy of commercial electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) temperature control technology. PLoS One, 2018; 13(11):e0206937. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30395592

5. Wagner J, Chen W, and Vrdoljak G. Vaping cartridge heating element compositions and evidence of high temperatures. PLoS One, 2020; 15(10):e0240613. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33075091

6. Orellana-Barrios MA, Payne D, Mulkey Z, and Nugent K. Electronic cigarettes—A narrative review for clinicians. The American Journal of Medicine, 2015; 128(7):674-81. Available from: https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(15)00165-5/pdf

7. World Health Organization (WHO), Electronic nicotine delivery systems. Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Moscow, Russian Federation 2014. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/fctc/PDF/cop6/FCTC_COP6_10-en.pdf?ua=1.

8. Therapeutic Goods Administration. Testing of nicotine vaping products. Australian Government, Department of Health, 2022. Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/testing-nicotine-vaping-products

9. Gilbert HA. Smokeless non-tobacco cigarette, 1965, Google Patents. Available from: https://www.google.com/patents/US3200819.

10. Grana R, Benowitz N, and Glantz SA. Background paper on e-cigarettes (electronic nicotine delivery systems), 2013. Available from: http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/13p2b72n.

11. Bauld L, Angus K, de Andrade M, and Ford A, Electronic cigarette marketing: current research and policy. Cancer Research UK; 2016. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/electronic_cigarette_marketing_report_final.pdf.

12. When did vaping start? - My first vape. Vaporesso, 2020. Available from: https://www.vaporesso.com/blog/when-did-vaping-start.

13. Jenkins C, Morgan J, and Kelso C. Synthetic cooling agents in Australian-marketed e-cigarette refill liquids and disposable e-cigarettes: trends follow the U.S. market. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2023. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntad120

14. Tobacco Tactics. E-cigarettes. 2023. Available from: https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/e-cigarettes/

15. Tehrani H, Rajabi A, Ghelichi-Ghojogh M, Nejatian M, and Jafari A. The prevalence of electronic cigarettes vaping globally: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Public Health, 2022; 80(1):240. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36415010

16. Technavio. Global E-cigarette market 2016-2020. 2016. Available from: https://www.technavio.com/report/global-health-and-wellness-e-cigarette-market

17. Ali FRM, Seidenberg AB, Crane E, Seaman E, Tynan MA, et al. E-cigarette unit sales by product and flavor type, and top-selling brands, United States, 2020-2022. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2023; 72(25):672-7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37347717

18. Ali FRM, Seaman EL, Crane E, Schillo B, and King BA. Trends in US e-cigarette sales and prices by nicotine strength, overall and by product and flavor type, 2017-2022. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2023; 25(5):1052-6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36580384

19. King BA, Gammon DG, Marynak KL, and Rogers T. Electronic cigarette sales in the United States, 2013-2017. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2018; 320(13):1379-80. Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/2705175

20. Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J, Binns S, Vera LE, et al. Vaping versus JUULing: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tobacco Control, 2019; 28(2):146-51. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29853561

21. Guzman Z. Juul surpasses Facebook as fastest startup to reach decacorn status. Yahoo Finance, 2018. Available from: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/juul-surpasses-facebook-fastest-startup-reach-decacorn-status-153728892.html

22. Myers M. Altria-Juul deal is alarming development for public health and shows need for strong FDA regulation, in Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids,2018: WASHINGTON, D.C. Available from: https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/press-releases/2018_12_20_altria_juul.

23. Hendlin YH, Elias J, and Ling PM. The pharmaceuticalization of the tobacco industry. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2017; 167(4):278-80. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28715843

24. Mathis W. BAT launches high-tech vape in UK to fend off Juul, IQOS. Bloomberg, 2018. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-12-11/bat-launches-high-tech-vape-in-the-u-k-to-fend-off-juul-iqos

25. Philip Morris International. E-vapor products. 2018. Available from: https://www.pmi.com/smoke-free-products/mesh-taking-e-cigarettes-further.

26. Sreeramareddy CT, Acharya K, and Manoharan A. Electronic cigarettes use and ‘dual use’ among the youth in 75 countries: estimates from Global Youth Tobacco Surveys (2014–2019). Scientific Reports, 2022; 12(1):20967. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36470977

27. Dessaix A, Jardine E, Freeman B, and Kameron C. Undermining Australian controls on electronic nicotine delivery systems: illicit imports and illegal sales. Tobacco Control, 2022; 31(6):689-90. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36265869

28. Chenoweth N. Vapers’ facelift: new pitch, same sponsors. Financial Review, 2022. Available from: https://www.afr.com/rear-window/vapers-facelift-new-pitch-same-sponsors-20220628-p5ax9k

29. Chenoweth N. The secret money trail behind vaping. Financial Review, 2021.

30. Han E. Secret industry funding of doctor-led vaping lobby group laid bare. The Sydney Morning Herald, 2018. Available from: https://www.smh.com.au/healthcare/secret-industry-funding-of-doctor-led-vaping-lobby-group-laid-bare-20180823-p4zzc5.html

31. Han E. 'Independent' doctor-led vaping group accepts tobacco-tainted funding. Brisbane Times, 2018. Available from: https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/healthcare/independent-doctor-led-vaping-group-accepts-tobacco-tainted-funding-20181004-p507rq.html?ref=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_source=rss_feed