Smoking of tobacco as we know it today, in the form of manufactured or ‘factory-made’ cigarettes, became common in Australia in the late-1800s. Pipe and cigar smoking was already widespread among men, but the convenience and ready availability of the cigarette soon made it a popular alternative.1 Manufactured cigarettes were supplied to Australians and their allies in the trenches of World War I,1 and by the end of World War II, nearly three-quarters of Australian men and one quarter of women smoked, the majority using cigarettes (see also Section 1.1).

Similar changes in smoking behaviour had occurred in Western Europe and North America, and with them, a marked escalation in lung cancer death rates and the growing suspicion that cigarette use was implicated in this trend. By 1950, findings from two very important studies had been published in the medical literature and it was concluded that cigarette smoking and lung cancer appeared to be causally linked.2,3 The seminal UK doctors study initiated by Doll and Hill that published findings in 1950, 1954, 1964, 1976, 1994 and 2004 estimated that smoking kills about half of all persistent users, half of whom die in middle age.4-8

Several series of authoritative, landmark reports have since been published by national and international agencies,1 documenting the health risks of smoking and calling for action to help halt the smoking epidemic.9-11 Of these, the most regular series has been that issued by the Office of the US Surgeon General.9 Since 1964, 34 comprehensive and rigorous reports on various aspects of tobacco and health have been issued by the US Surgeon General, repeating the conclusion that “smoking remains the leading preventable cause of premature disease and death in the United States.”12 Each report has strengthened prior conclusions on the role of smoking in causing a range of poor health outcomes and has expanded the list of diseases and other adverse health effects caused by smoking.

3.0.1 The health consequences of smoking – major conclusions from recent US Surgeon General reports

The 2004 report of the US Surgeon General, The Health Consequences of Smoking, included the following major conclusions:13

- Smoking harms nearly every organ of the body, causing many diseases and reducing the health of people who smoke in general.

- Smoking cigarettes with lower machine-measured yields of tar and nicotine provides no clear benefit to health.

- The list of diseases caused by smoking has been expanded to include abdominal aortic aneurysm, acute myeloid leukaemia, cataract, cervical cancer, kidney cancer, pancreatic cancer, pneumonia, periodontitis and stomach cancer.

In addition, the 2014 report of the US Surgeon General, The Health Consequences of Smoking – 50 Years of Progress, published these major conclusions in regard to the health effects of smoking:12

- The century-long epidemic of cigarette smoking has caused an enormous avoidable public health tragedy. Since the first Surgeon General’s report in 1964 more than 20 million premature deaths [in the U.S] can be attributed to cigarette smoking.

- The tobacco epidemic was initiated and has been sustained by the aggressive strategies of the tobacco industry, which has deliberately misled the public on the risks of smoking cigarettes.

- Even 50 years after the first Surgeon General’s report, research continues to newly identify diseases caused by smoking, including such common diseases as diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, and colorectal cancer.

- In addition to causing multiple diseases, cigarette smoking has many other adverse effects on the body, such as causing inflammation and impairing immune function.

- The burden of death and disease from tobacco use in the United States is overwhelmingly caused by cigarettes and other combusted tobacco products; rapid elimination of their use will dramatically reduce this burden.

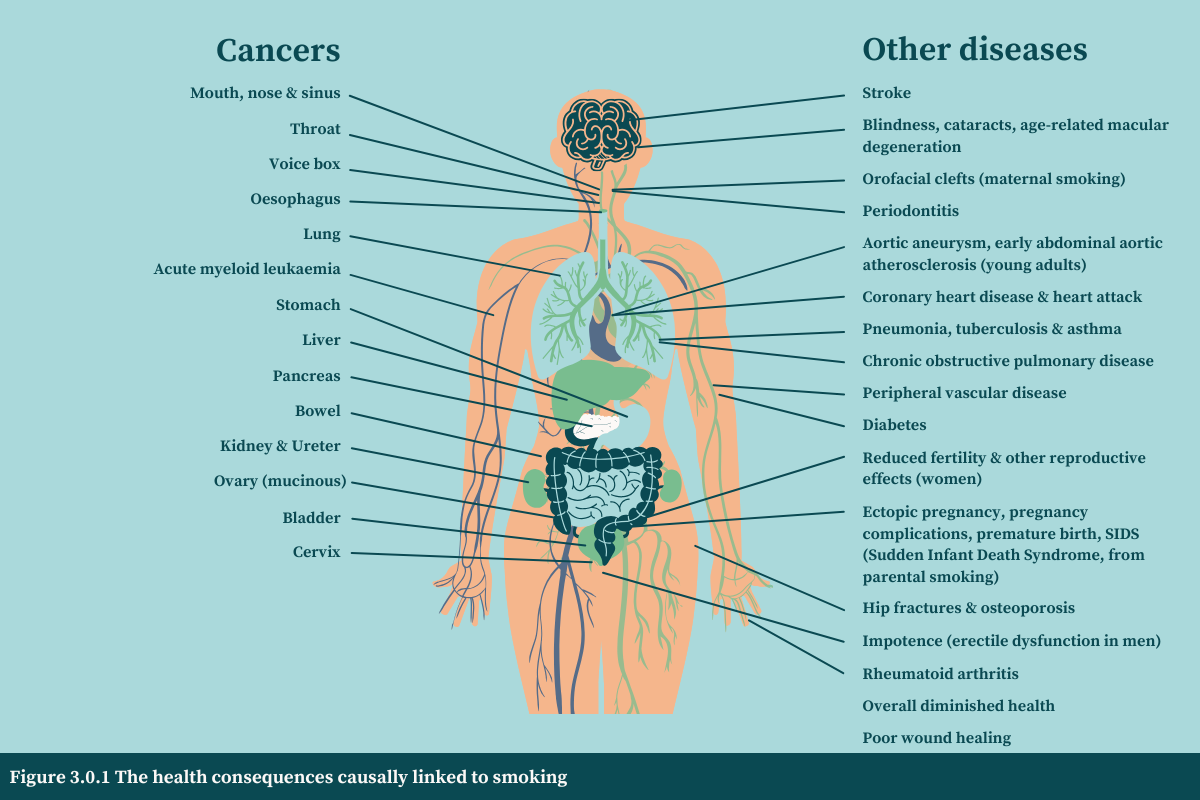

Figure 3.0.1 shows each of the conditions caused by smoking as identified in the Surgeon General’s and IARC reports.

3.0.2 Tobacco—a leading preventable cause of death and disease globally

Tobacco use causes the sickness and death of millions of people each year. The addictive nature of tobacco, the commonness of its use globally, and its extensive and wide-ranging health consequences have together made the tobacco pandemic one of the most harmful threats to human health in modern times. The global tobacco pandemic is summarised by these key statistics:

- Nearly 1.3 billion people are tobacco users. An estimated 1.27 billion people worldwide used tobacco products in 2020.15 The majority live in low- and middle-income countries.16

- Approximately one in five people use tobacco. In 2020, an estimated 22.3% of the world’s people were users of tobacco:15 36.7% of men and 7.8% of women.

- Worldwide, tobacco use causes the death of approximately one in 10 people each year.17

- Over 7 million people die each year from tobacco use. In 2021, 7.25 million people died due to tobacco exposure (tobacco smoking, chewing tobacco, or secondhand smoke exposure), which made up 5.2% of total deaths of women and 15.1% of total deaths in men.17

- Cardiovascular diseases, cancer and chronic respiratory diseases are the most common tobacco-associated diseases that contribute to the burden of disease (see Section 3.30).17

- Most tobacco-related deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. In 2019, an estimated 77.5% of the deaths of people that were attributed to tobacco occurred in low- and middle-income countries.18

- Tens of thousands of children die each year from exposure to secondhand smoke. In 2021, over 42,000 children died from illnesses related to second-hand smoke.19

- A person who smokes throughout their adult life loses on average a decade of life.20,21

- The average loss of life is approximately 20 minutes per cigarette smoked for people who smoke for their whole lives. This is 17 minutes per cigarette lost for men and 22 minutes for women.22

- Smoking primarily decreases the relatively healthy middle years rather than shortening the period at the end of life. So a 60-year-old person who smokes may have the health profile of a typical 70-year-old non-smoker.22

- The worldwide total economic cost of smoking is over US$1.4 trillion per year. This is the estimated cost of health expenditures and productivity losses together in 2012.23,24

- Smoking is estimated to kill a billion people in the 21 st century. It is estimated that on the basis of recent rates of smoking initiation and cessation, smoking—which killed about 100 million people in the 20th century—will kill about one billion in the 21st century.20,25

3.0.3 Tobacco—a leading preventable cause of death and disease in Australia

Tobacco use is still the leading preventable risk factor for death in Australia and has been for decades. The tobacco pandemic in Australia is summarised by these key statistics:

- Almost 1 in 10 people in Australia regularly smoke. This is 9.4% of people aged 14 years and over who regularly smoke (daily or weekly) and 8.3% who smoke daily (see Section 1.3.1).

- The Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated that 1.98 million people aged 15 and over in Australia smoked daily in 2021–2022.26

- Smoking is more common among specific groups of people in Australia, including those of lower socioeconomic status, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, people with mental health disorders, people with substance use disorders, and people experiencing homelessness27—see Chapter 8 and InDepth 9A.

- Smoking prevalence in Australia has reduced considerably over the past three decades, from 26.6% in 1995 to 10.0% in 2022–2023 (see Section 1.3.2 and Table 1.3.1).

- Tobacco use was the leading preventable cause of death in Australia in 2024 (see Table 3.0.1) and the 2nd leading preventable risk factor contributing to the total burden of disease (see Section 3.30 and Table 3.0.1).28

- Smoking is responsible for the deaths of over 24,000 people in Australia every year. The deaths of 24,285 Australians aged 45 years or over were attributable to smoking in 2019. At least 66 people die each day from smoking, making up one in 6 deaths (15.3%) in people aged 45 and above.29,30

- In the 60 years from 1960 to 2020, smoking is estimated to have killed 1,280,000 people in Australia.31

- Smoking-related deaths in men are nearly double those of women in Australia. There were 19.4% of deaths of men and 11.1% of deaths in women aged 45 and over in 2019 that were attributable to smoking.29,30

- Smoking leads to dying prematurely. It is estimated to cause nearly one-quarter (23.3%) of deaths in those aged 45-75 years in Australia.29,30

- Smoking rates among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have substantially reduced over the past three decades, from 54.5% in 1994 to 31.5% in 2022/2023 (see Section 8.3.2 and Table 8.3.1).

- Smoking is the cause of death for half of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples aged 45 years or over. Only 40% of those who smoke live past the age of 75 years, compared to 80% of those who never smoked.32

- Among all Australians, tobacco use was responsible for more than three times as many people dying compared to alcohol, the next most common cause of death by a drug, in 2024.28

- People who smoke throughout their life in Australia lose, on average, a decade of life.21

- Chronic respiratory diseases (36.1%), cancer (15.4%) and cardiovascular diseases (5.1%) were the most common tobacco-associated diseases that contribute to the burden of disease in Australia in 2024 (see Section 3.30).

- Light smoking greatly increases the risks of disease and early death in Australia. People who smoke between one and 14 cigarettes daily had 21-fold higher risk of dying from chronic lung disease, 13-fold higher for lung cancer, and 2-fold higher risk of dying from heart disease, compared to people who have never smoked.29,30

- The total economic cost of smoking in Australia was estimated to be AUD $136.9 billion for 2015–16. This cost included $19.2 billion in tangible costs and $117.7 billion in intangible costs (see Section 17.2.5.2 and Table 17.2.4

3.0.4 The health benefits of smoking cessation

As recognised by reports of the US Surgeon General and other major studies,13,33,34 quitting smoking has immediate as well as long-term benefits, reducing risks for diseases caused by smoking and improving health in general:

- Smoking cessation is beneficial at any age. Smoking cessation improves health status and enhances quality of life.

- Smoking cessation reduces the risk of premature death and can add as much as a decade to life expectancy.

- Smoking cessation reduces the substantial burden on people who smoke, health care systems and society, including smoking attributable healthcare expenditures.

- Smoking cessation reduces the risk of many adverse health effects, including reproductive health outcomes, cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cancer. Quitting smoking is also beneficial to those who have been diagnosed with heart disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (see Chapter 7, Section 7.1 for further details).

Australian research has similarly highlighted the substantial benefits of quitting:

- Quitting smoking reduces the risk of early death, with increasing time since cessation associated with greater reductions in risk. For those who quit prior to age 45, their risk of premature death was similar to those who had never smoked.21,29,30

- For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, quitting at any age had substantial benefits on the risk of dying early compared to continued smoking. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who quit later in life (after the age of 45) had approximately half the risk of early death compared to those who continued smoking.32

The US Surgeon General’s reports have provided a detailed review of definitions of causality of disease, and how measures of causality may be applied. Causality is determined by evaluating the available evidence and considering it against well-established criteria. The more that an observed association fulfils the criteria, the more likely it is that a causal relationship can be inferred. These criteria are outlined in the US Surgeon General’s Report for 2004:13

Consistency: This refers to the persistence of the finding of an association between exposure and outcome in a number of methodologically valid studies undertaken in a range of settings. This helps ensure that possible confounding effects are eliminated and also increases the statistical validity of the finding through the accumulation of additional evidence.

Strength of association: Strength refers both to magnitude of the association, and to its statistical strength. The greater the measured association and the more sound its statistical basis, the less likely it is that the findings are influenced by chance, bias, or unmeasured or poorly controlled confounding factors. However, the observed association must also have a plausible basis in understood biological processes.

Specificity: Specificity refers to the degree to which exposure to the suspected disease-causing agent can predict outcome. Other biological and epidemiological factors may need to be taken into account. For example, not all people who smoke develop lung cancer, and not all cases of lung cancer are caused by smoking. However, the extremely high relative risk for lung cancer in those who smoke, and the high percentage of lung cancers attributable to smoking, gives the association between smoking and lung cancer “a high degree of specificity”.

Temporality: Exposure to the causative factor must precede the onset of the disease. Considered alone, temporality is a poor predictor of causality, but no association can be considered to fulfil the criteria for causality if temporality is not satisfied.

Coherence, Plausibility and Analogy: Taken together, these three criteria require that the proposed causal relationship must not defy known scientific principles, and that it must be biologically plausible and consistent with experimentally demonstrated biological mechanisms and other relevant patterns.

Biologic Gradient (Dose–Response): This criterion refers to the observation of increased effect (for example incidence of disease) in response to increased dose (heavier and/or longer duration of smoking). Meeting this criterion forms a strong support for causality, except in the unlikely event that there is an unidentified confounder, which happens to be varying in the same manner as the observed dose and which could account for the measured association. Virtually all health outcomes causally linked to smoking have demonstrated a dose–response relationship of some description.

Experiment: This criterion refers to naturally occurring “experiments” that might be considered to imitate the conditions of a properly conducted experiment in a scientific environment, and whose outcomes might have the force of a true experiment. An example of a ‘natural experiment’ in the smoking arena is assessing the health consequences of quitting smoking. To attribute observed improvements in health outcomes to factors other than smoking cessation would necessitate identifying alternative influences and demonstrating that those who continued smoking had also attained a health benefit where that alternative influence was present .

The more closely an association fulfils the above criteria, the stronger its claim to causality. Not all inferences of causality will necessarily satisfy all criteria. For example, where biological mechanisms may not be completely understood, causality may still be justified by satisfaction of other criteria, such as consistency and strength of association. Those applying the criteria must weigh the all of the scientific evidence and make a multidisciplinary judgement.13

Related reading

Relevant news and research

A comprehensive compilation of news items and research published on this topic (Last updated November 2024)

Read more on this topic

Test your knowledge

References

1. Walker R. Under fire. A history of tobacco smoking in Australia Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1984.

2. Doll R and Hill AB. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. British Medical Journal, 1950; 2(4682):739-48. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14772469

3. Wynder E and Graham E. Tobacco smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchogenic carcinoma. JAMA, 1950; 143:329-36. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2623809/pdf/15744408.pdf

4. Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, and Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years' observations on male British doctors. British Medical Journal, 2004; 328(7455):1519. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15213107

5. Doll R and Hill AB. Mortality in Relation to Smoking: Ten Years' Observations of British Doctors. British Medical Journal, 1964; 1(5395):1399-410. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14135164

6. Doll R and Peto R. Mortality in relation to smoking: 20 years' observations on male British doctors. British Medical Journal, 1976; 2(6051):1525-36. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1009386

7. Doll R and Hill AB. The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits: a preliminary report. British Medical Journal, 1954; 1(4877):1451–5. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2085438/

8. Doll R, Peto R, Wheatley K, Gray R, and Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 40 years' observations on male British doctors. British Medical Journal, 1994; 309(6959):901-11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7755693

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Surgeon General's Reports on Smoking and Tobacco Use. 2025. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco-surgeon-general-reports/about/index.html.

10. Royal College of Physicians. Fifty years since Smoking and health. Progress, lessons and priorities for a smoke-free UK., London, UK: Royal College of Physicians, 2012. Available from: https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0924/4392/files/fifty-years-smoking-health.pdf?2801907981964551469.

11. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Tobacco. IARC, 2024. Available from: https://www.iarc.who.int/risk-factor/tobacco/.

12. US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress. A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK179276.pdf.

13. US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2004. Available from: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/tobacco/sgr/2004/index.htm.

14. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Personal habits and indoor combustions. IARC Monographs Vol. Volume 100 E A review of human carcinogens.Lyon, France: IARC; 2012. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304391/.

15. World Health Organization. WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco use 2000-2025. Geneva: WHO Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO., 2021. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/348537/9789240039322-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

16. G. B. D. 2015 Tobacco Collaborators. Supplemental Table S2; Supplementary appendix 2. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet, 2021; 397(10292). Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/cms/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01169-7/attachment/2e2348a0-b9ec-4da4-9d00-3ba983a8c04c/mmc2.pdf

17. G.B.D. 2021 Tobacco Collaborators. Global health metrics: Tobacco smoke—Level 2 risk. 2021. Available from: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/diseases-injuries-risks/factsheets/2021-tobacco-smoke-level-2-risk.

18. G. B. D. Tobacco Collaborators. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable disease burden in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet, 2021; 397(10292):2337-60. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34051883

19. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD results. Seattle, USA: University of Washington, 2024. Viewed: Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

20. Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, Rostron B, Thun M, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 2013; 368(4):341-50. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23343063

21. Banks E, Joshy G, Weber MF, Liu B, Grenfell R, et al. Tobacco smoking and all-cause mortality in a large Australian cohort study: findings from a mature epidemic with current low smoking prevalence. BMC Medicine, 2015; 13(1):38. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25857449

22. Jackson SE, Jarvis MJ, and West R. The price of a cigarette: 20 minutes of life? Addiction, 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39734064

23. World Health Organization. WHO technical manual on tobacco tax policy and administration. Geneva: WHO; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2021. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/340659/9789240019188-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

24. Goodchild M, Nargis N, and Tursan d'Espaignet E. Global economic cost of smoking-attributable diseases. Tobacco Control, 2018; 27(1):58-64. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28138063

25. Jha P and Peto R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. New England Journal of Medicine, 2014; 370(1):60-8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24382066

26. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Smoker status, Australia 2021-22: Data downloads: Insights into Australian smokers, 2021-22. ABS, 2022. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/insights-australian-smokers-2021-22.

27. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Insights into Australian smokers, 2021-22: Snapshot of smoking in Australia. ABS, 2022. Available from: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/insights-australian-smokers-2021-22.

28. Australian Institute for Health and Welfare. S6: Data tables: ABDS 2024 National estimates for Australia. Australian burden of disease study 2024. Canberra, Australia: AIHW, 2024. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/burden-of-disease/australian-burden-of-disease-study-2024/contents/about.

29. Joshy G, Soga K, Thurber KA, Egger S, Weber MF, et al. Relationship of tobacco smoking to cause-specific mortality: contemporary estimates from Australia. BMC Medicine, 2025; 23(1):115. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39994694

30. Australian National University. Policy Brief: Deaths related to tobacco smoking: contemporary Australian estimates. Canberra, Australia: ANU, 2025.

31. Peto R, Lopez AD, Pan H, Boreham J, and Thun M. Mortality from smoking in developed countries 1950 - 2020. 2015. Available from: http://gas.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/tobacco/contents.htm

32. Thurber KA, Banks E, Joshy G, Soga K, Marmor A, et al. Tobacco smoking and mortality among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults in Australia. International Journal of Epidemiology, 2021; 50(3):942-54. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33491081/

33. US Department of Health and Human Services. Smoking cessation. A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health 2020. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco-surgeon-general-reports/reports/2020-smoking-cessation/.

34. Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V, et al. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet, 2013; 381(9861):133-41. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23107252