|

Last updated: September 2020

Suggested citation: Wood, L, Letcher, T, Hanley-Jones, S & Winstanley, M. 5.17 Factors influencing uptake of smoking later in life. In Greenhalgh, EM, Scollo, MM and Winstanley, MH [editors]. Tobacco in Australia: Facts and issues. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2020. Available from: https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-5-uptake/5-17-factors-influencing-uptake-of-smoking-later-i

|

Although most smoking behaviour historically has been ‘seeded’ during the early teenage years, some individuals begin smoking after this period. Since the beginning of the millennium, uptake appears to have been occurring at a somewhat later age.

While the majority of Australia’s contemporary smokers took up smoking before the age of 18, a significant and growing minority appear to be taking it up after that age. The late teens and early 20s appear to be a second important period when susceptible non-smokers may start to experiment with cigarettes; occasional smokers may become established smokers; and established smokers may increase their daily consumption levels. 1

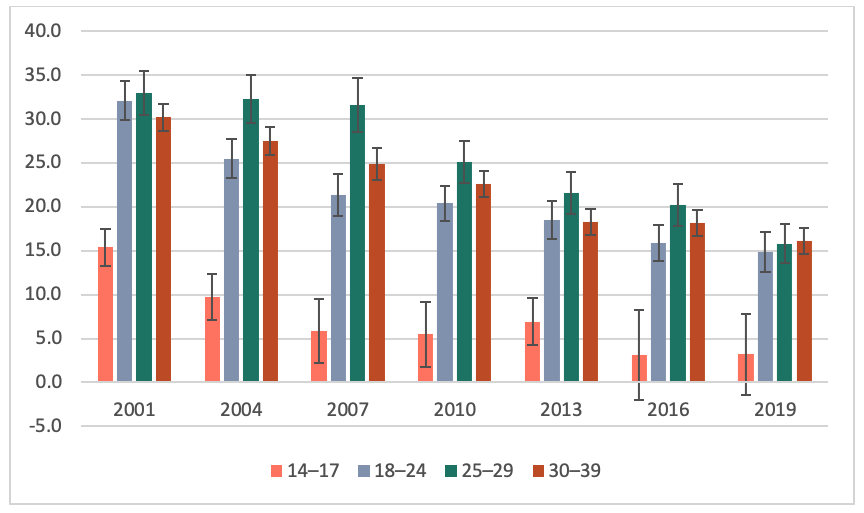

The 2019 National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) showed that those aged 18 –24 years were much more likely than younger teenagers (aged 14–17 years) to smoke daily (9.2% +/-1.8% vs. 1.9%* +/-1.2%), while in the next oldest age group, aged 25‒29 years, 11.3% (+/-1.9) smoked daily, with similar levels of smoking among people in their late 20s and 30s. 2 Figure 5.17.1 shows the prevalence of current smoking (daily or less often than daily) for 14–17-year-olds compared to other age groups under 40 years of age for all years of the survey since 2001. 2

Figure 5.17.1 shows that prevalence is significantly lower among teenagers than among all other age groups under 40 years of age. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimates that roughly 600,000 +/-40,000 young adults 18–24 were smokers in 2001 compared to 200,000 +/- 20,000 teenagers 14–17 years in 2020 (refer Table 2.8 in AIHW 2020 (reference 2). While young adult smokers out-numbered teenage smokers by roughly three to one in 2001, by 2019, young adult smokers out-numbered teenage smokers by roughly ten to one (400,000 +/- 50,000 compared to 40,000 +/- 20,000).

The percentage of Australians currently aged 18–49 years who have ever had a full cigarette, who had that first cigarette after the age of 18, increased significantly in 2019 (35.8%) compared to 2016 (31.4%). 2 This is almost double the percentage in 2001—refer Figure 5.17.2.

The later teenage years are associated with major life changes such as finishing school, gaining greater mobility and independence through learning to drive, travelling, changing peer groups, entering the workforce, and starting higher education. For some young adults, significant changes such as these also signify a period of vulnerability, where feelings of stress, insecurity and uncertainty may surface, along with new social pressures. These transitions mark a period of major influence on smoking behaviour. 3,4

Longitudinal research from Switzerland in 2016 found a strong association between young adult males transitioning out of the parental home and daily smoking initiation when compared to those who continued living at home. Moving out to live with peers was an especially strong predictor of initiation. 5 Similarly, moving overseas for further study has been found to be a risk factor for smoking initiation. A 2020 study found US students’ cigarette smoking increased three-fold while studying abroad. Patterns of use were found to vary significantly by locations of study, and tended to mirror smoking behaviour of young adults native to the area. 6 In the tertiary education setting more generally, those who smoke are more likely to rate social activities over academic or sporting achievement, to have achieved lower academic grades, and are less likely to follow religious beliefs. 7,8 Smoking initiation among male Iranian university students for instance, was influenced significantly by frequent gathering in the presence of smokers, with the risk of trying a cigarette for the first time increasing alongside the number of exposures. Students who were in the presence of smokers’ gatherings 10 or more times, were four times more likely to report having tried a cigarette for the first time. 9 Research from the US has shown friends’ use of tobacco products to be associated with higher levels of use among university students, as is tobacco use by other social influences, such as parents and siblings. 10

Taking up employment in an area with a strong culture of smoking, such as the military, has been shown to be associated with smoking uptake. 11 , 12 A 2019 study found a significant amount of tobacco initiation occurring following enlistment of new recruits into the US Air Force (USAF). Prevalence of cigarette use in the USAF ranged between 24% and 25.1%, with 12.6% of individuals who had never smoked initiating smoking by the completion of their technical training. 13 Research has shown that in some occupations there are perceived benefits to being a smoker. In many low-paid, unskilled jobs frequented by young people, becoming a smoker meant more work breaks and opportunities for socialisation, as well as being a way to deal with stress and boredom. 14

Substance use has been found to be associated with an increased risk of smoking initiation. High-risk alcohol consumption and smoking uptake have been demonstrated among university students in Japan 15 and in the US. 16 Research drawing on data from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Women’s Health examined changes in smoking behaviour among a large sample of young women over a 10 year period, from an initial age of 18–23 years in 1996. 3 , 17 Analyses over four time points found uptake of smoking to be associated with binge drinking and use of illicit drugs. 3 , 17 Analysis of more recent data from the study focussing on women in their early 20s has found that use of e-cigarettes was associated with subsequent uptake of smoking. 18

Other risk factors associated with late uptake of smoking include exposure to trauma (such as interpersonal violence or unwanted sexual contact) in early adulthood, 19 not living in a smokefree home 20 and being at the younger end of a cohort age group. 20, 21 Those who have prior smoking experience, who have expressed an intention to smoke, and who performed less well at school are more likely to initiate smoking after having left secondary school. 21

There is evidence that moderate to high physical activity acts as a protective factor against the adoption of smoking among university students 9, 15, 22 and against relapse among young Australian female ex-smokers (for those aged in their late 20s to early 30s). 17 Marriage or being in a committed relationship has also been associated with a lower likelihood of taking up smoking or continuing to smoke and a greater chance of quitting and of remaining an ex-smoker. 3, 17

The strategic importance of young adults as a target group for the tobacco industry makes it a logical and critical focus of attention; internal industry documents highlight the industry need for young smokers to renew the market for tobacco and the crucial role of young smokers’ brand loyalty compared with older smokers. 23 As teenagers regard young adults as role models, it is likely that marketing to young adults helps to maintain adolescent interest in smoking. 20 In Australia, and overseas, there has been increased channelling of tobacco promotions into media significant to young adults, 24 including harnessing young adult social media influencers who have many young online followers for product promotion. 25 The tobacco industry’s focus on targeting young adults has been extensively examined in research undertaken in the US. 26, 27, 28 For further discussion, refer to Section 5.15.2, 5.15.3 and Chapter 11, Sections 11.7 and 11.11.5

* Estimate has a relative standard error of 25% to 50% and should be used with caution.

Relevant news and research

For recent news items and research on this topic, click here. ( Last updated November 2023)

References

1. Schofield P, Borland R, Hill D, Pattison P, and Hibbert M. Instability in smoking patterns among school leavers in Victoria, Australia. Tobacco Control, 1998; 7:149-55. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9789933

2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) 2019 key findings and data tables. Canberra: AIHW, 2020. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/3564474e-f7ad-461c-b918-7f8de03d1294/aihw-phe-270-NDSHS-2019.pdf.aspx?inline=true.

3. McDermott L, Dobson A, and Russell A. Changes in smoking behaviour among young women over life stage transitions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 2004; 28:330-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15704696

4. Jamner L, Whalen C, Loughlin S, Mermelstein R, Audrain-McGovern J, et al. Tobacco use across the formative years: A road map to developmental vulnerabilities. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 2003; 5(suppl.1):S71-87. Available from: http://ntr.oxfordjournals.org/content/5/Suppl_1

5. Bahler C, Foster S, Estevez N, Dey M, Gmel G, et al. Changes in living arrangement, daily smoking, and risky drinking initiation among young Swiss men: A longitudinal cohort study. Public Health, 2016. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27558957

6. Firth C, LaBrie JW, D'Amico EJ, Klein DJ, Griffin BA, et al. Changes in cigarette, e-cigarette, and cannabis use among U.S. College students studying abroad. Substance Use and Misuse, 2020:1-9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32364038

7. Rigotti NA, Lee JE, and Wechsler H. US college students' use of tobacco products: Results of a national survey. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2000; 284:699-705. Available from: http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/284/6/699

8. Lantz P. Smoking on the rise among young adults: Implications for research and policy. Tobacco Control, 2003; 12(suppl.1):i60–70. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=1766087&blobtype=pdf

9. Menati W, Nazarzadeh M, Bidel Z, Wurtz M, Menati R, et al. Social and psychological predictors of initial cigarette smoking experience: A survey in male college students. Am J Mens Health, 2014. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25326133

10. Windle M, Haardorfer R, Lloyd SA, Foster B, and Berg CJ. Social influences on college student use of tobacco products, alcohol, and marijuana. Substance Use and Misuse, 2017:1–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28524716

11. Conway TL. Tobacco use and the United States military: A longstanding problem [editorial]. Tobacco Control, 1998; 7:219-21. Available from: http://tc.bmjjournals.com

12. Chisick MC, Poindexter FR, and York AK. Comparing tobacco use among incoming recruits and military personnel on active duty in the United States. Tobacco Control, 1998; 7:236-40. Available from: http://tc.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/abstract/7/3/236

13. Little MA, Ebbert JO, Krukowski RA, Halbert JP, Kalpinski R, et al. Predicting cigarette initiation and reinitiation among active duty United States air force recruits. Subst Abus, 2019:1-4. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30883297

14. Delaney H, MacGregor A, and Amos A. "Tell them you smoke, you'll get more breaks": A qualitative study of occupational and social contexts of young adult smoking in Scotland. BMJ Open, 2018; 8(12):e023951. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30598486

15. Kiyohara K, Kawamura T, Kitamura T, and Takahashi Y. The start of smoking and prior lifestyles among Japanese college students: A retrospective cohort study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2010; 12(10):1043-9. Available from: http://ntr.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2010/08/28/ntr.ntq141.full

16. Reed M, McCabe C, Lange J, Clapp J, and Shillington A. The relationship between alcohol consumption and past-year smoking initiation in a sample of undergraduates. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 2010; 36(4):202–7. Available from: http://informahealthcare.com/doi/full/10.3109/00952990.2010.493591

17. McDermott L, Dobson A, and Owen N. Determinants of continuity and change over 10 years in young women's smoking. Addiction, 2009; 104(3):478-87. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02452.x/full

18. Melka A, Chojenta C, Holliday E, and Loxton D. E-cigarette use and cigarette smoking initiation among Australian women who have never smoked. Drug and Alcohol Review, 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32750198

19. Roberts M, Fuemmeler B, McClernon F, and Beckham J. Association between trauma exposure and smoking in a population-based sample of young adults. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2008; 42(3):266–74. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18295135

20. Gilpin E, White V, and Pierce J. What fraction of young adults are at risk for future smoking, and who are they? Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2005; 7:747-59. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16191746

21. Ellickson P, McGuigan K, and Klein D. Predictors of late-onset smoking and cessation over 10 years. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2001; 29:101-8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11472868

22. Halperin AC, Smith SS, Heiligenstein E, Brown D, and Fleming MF. Cigarette smoking and associated health risks among students at five universities. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 2010; 12(2):96-104. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20018947

23. Mangini. Younger adult smokers: Strategies and opportunities. San Francisco: Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, University of California, 2002. Available from: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/krx52d00

24. Harper T and Martin J. Under the radar - how the tobacco industry targets youth in Australia. Drug and Alcohol Review, 2002; 21:387-92. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12537709

25. No authors listed. Where there's smoke. Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, 2018. Available from: https://www.takeapart.org/wheretheressmoke/

26. Sepe E and Glantz SA. Bar and club tobacco promotions in the alternative press: Targeting young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 2002; 92(1):75–8. Available from: http://www.ajph.org/cgi/content/full/92/1/75/T1

27. Ling PM and Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: Evidence from industry documents. American Journal of Public Health, 2002; 92(6):908–16. Available from: http://www.ajph.org/cgi/content/full/92/6/908

28. Song A, Ling P, Neilands T, and Glantz S. Smoking in movies and increased smoking among young adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2007; 33:396-403. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17950405