While tax is the most substantial component of the price of tobacco products, tobacco companies employ numerous strategies to maximise the overall profitability their product ranges, including by providing products that seem affordable even as taxes increase. This section describes these strategies in detail, setting out evidence from international literature and real-world data from Australia. Topics covered include:

As in other industries, the costs of raw materials, manufacturing, promotion and distribution of tobacco products are important in determining profits to tobacco growers, manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers. However, because tax is such a substantial component, the level and nature of tobacco duties, fees and taxes—rather than production and marketing factors—historically have been the main determinants of the final retail price of cigarettes in Australia, as in most developed countries. The portion of final retail price that is controlled by tobacco manufacturers and retailers is highly manipulated. Most markets are dominated by a small number of tobacco companies, for example, there are three major international tobacco companies operating Australia. These tobacco companies enjoy strong pricing power, enabling them to employ sophisticated product development and pricing strategies to blunt the impact of tax increases and facilitate price minimising behaviours among people who smoke.1,2 Such tactics often have additional promotional advantages—see Chapter 10, Sections 10.8 and 10.9.

The tactics that are most effective for tobacco companies will depend on the tax structure and other factors such as the availability of cheaper alternative tobacco products (such as roll-your-own tobacco, bidis, or oral tobacco). Several international reviews of tobacco industry pricing have identified strategies commonly used in both high and low and middle- income countries to undermine the impact of tax increases.2-4 These are summarised in Table 13.4.1. The remainder of this section outlines how these strategies, and others specific to the Australian context, have been used by tobacco companies to blunt the impact of tax increases on Australian consumers, resulting in a tobacco market that is highly diverse in terms of product offerings and highly dispersed in terms of pricing. Changes in the nature of the factory-made cigarette and roll-your-own tobacco markets due to these tactics will be presented, as well as data on changes in consumer preferences over time.

Consumers can make use of price minimisation strategies in combination, amplifying available discounts.5,6 For example, people who purchase budget brands may also seek out bulk-buy discounts, or area-based discounting. Disadvantaged people who smoke are more likely to engage in price minimising strategies,7,8 particularly switching to cheaper tobacco products9 Price tiers (segments) and discounts have been shown experimentally to increase purchase likelihood among young adults.10 It has also been shown that cessation behaviours are reduced among those who engage in price minimisation,6 undermining the intended impact of a tax increase among those who should benefit most.

13.4.1 Price dispersion

The diversity of price segments, pack sizes, and product types (e.g. extra-long cigarettes, menthol capsules, slims) that have been available on the Australian market—even in an environment where almost all forms of advertising are banned—has allowed companies to effectively promote tobacco products by creating consumer interest and points of differentiation simply through the brand name and descriptors of the product. (See also Chapter 10, Sections 10.8 and 10.9). These product features also create high levels of price dispersion. Price dispersion refers to the price of the cheapest product on the market relative to the most expensive.11 That is, it is the ratio of cheap products to expensive, calculated by taking the price of the cheapest product and dividing it by the price of the most expensive. Dispersion close to 1, or 100%, represents little variation in prices across the market, whereas wider dispersion (closer to 0%) represents greater affordability of cheap packs relative to expensive. Dispersion of 50% means that the cheapest product is half the price of the most expensive.

The impact of price dispersion is three-fold: the availability of very cheap products on the market for smokers to switch to following a tax increase (known as down-trading) allows smokers who might otherwise quit to continue smoking; higher priced products can make mid-priced and low-priced products appear more affordable by comparison; and continuing sales of higher priced products maximise profits from those smokers who are less sensitive to price.2,11,12

In markets dominated by packs of 20 cigarettes, dispersion calculated using prices per stick will be the same as or very similar to dispersion calculated using pack prices. However, in markets such as Australia, price per pack across a range of pack sizes has been more prominent than price per stick to smokers at the point of purchase. Therefore, dispersion of upfront pack or pouch purchase prices has also needed to be considered in the Australian market. In markets with popular alternative tobacco products, such as RYO tobacco in Australia, the dispersion or gap across types of tobacco products is also important,13 in addition to dispersion within these tobacco types. Figure 13.4.1 shows differences in price dispersion across stick price and pack price, and dispersion across FMC and RYO products at March 2025.

At March 2025, the cheapest FMC stick was half (50.2%) the price of the most expensive FMC stick. RYO stick prices were slightly less dispersed, with the cheapest RYO stick costing 73% of the price of the most expensive. Pack prices were much more dispersed for both FMC and RYO products: the cheapest FMC pack cost less than one-third (28%) of the price of the most expensive and the cheapest RYO pouch was less than one-quarter (23%) of the price of the most expensive.

These differences in dispersion show the impact of the wide range of pack sizes on the FMC and RYO markets: the cheapest packs were 20 sticks and 15 grams, while the most expensive were 50 sticks and 50 grams. However, stick price dispersion is more influenced by price segmentation: the cheapest FMC products per stick was a pack of 20s from a supervalue brand and the most expensive was a pack of 25s from a premium brand. The cheapest RYO product per stick was from a 30-gram pouch from a brand that has FMC products in the supervalue market segment, while the most expensive per stick was from a 50 gram pouch from a long-standing brand that has FMC products in the mainstream segment.

Figure 13.4.1 also shows the gap in pricing between FMC and RYO products. The cheapest RYO stick (assuming 0.6 grams of tobacco per cigarette) was 94% of the price of the cheapest FMC product. While the upfront cost of the cheapest RYO pouch was around 22% more expensive than the cheapest FMC pack, this 30-gram pouch would yield 50 cigarettes of 0.6 grams each, compared to the 20 sticks offered in the FMC pack. The highly dispersed Australian tobacco market allows tobacco companies to create an impression among consumers that particular tobacco products are cheaper, or provide better value, on a per stick or per pack basis.

13.4.2 Pack and pouch sizes

In the early 1900s, cigarettes were commonly sold in packets of 10 or 20 or in tins of 50. These were similar in size to the tins in which loose tobacco was commonly sold. With the advent of plastic wrapping, however, these tins disappeared and by 1960 the vast majority of cigarettes were sold in packets of 20. Increasing prices, due to escalating state licence fees starting in the mid-1970s and extending over the 1980s and early- to mid-1990s (see Section 13.6.3.3), and—at the time—Australia’s unique excise system based on weight and ad valorem fees levied on the value of wholesale sales, created an incentive for manufacturers to produce larger packs with lower tobacco weight cigarettes. This started with Winfield 25s (“Five smokes ahead of the rest”) in 1976, then grew to packs of 30s, 40s, and 50s. State licence fees were abolished in 1997 and the excise system was reformed in 1999. However, large packs had become an entrenched feature of the Australian market by this time, and packs as large as 50 sticks continue to be sold in 2025.

Pack size ‘creep’ such as that which occurred in Australia may be concerning for reasons in addition to price. International evidence suggests that cigarette pack size is positively associated with cigarette consumption. People who tend to use larger pack sizes are often older, and heavier tobacco consumers, and reductions in consumption are positively associated with quitting attempts and success.14-16 Greenland and colleagues17 note that purchasing a large volume of an unhealthy product can stimulate additional consumption. When supply is plentiful, consuming, for example, five cigarettes from a full large pack may appear unremarkable. However, when supply is low, consuming the same quantity of cigarettes would seem more significant.

Examination of previously confidential tobacco industry documents indicates that tobacco companies have been well aware of the role of pack size in promoting and maintaining smoking behaviours.18 Large packages were recognised as offering value for money and convenience for heavier smokers. Small packages were understood to be cheaper upfront, matched consumption rates of newer and lighter users, and increased products’ novelty, ease of carrying and perceived freshness. Research on pack size use from Australians who smoke shows that larger size packs are more popular than mid-size packs for females, those with lower incomes, lower education levels, for those who smoke daily, and those who have a high level of nicotine dependence.19

13.4.2.1 Current and forthcoming Australian pack size regulations

FMC packs smaller than 20 have been banned for several decades in all states and territories, and pouches smaller than 25g are banned in Queensland and the Northern Territory20—see Chapter 5, Section 5.13). Packs that exceed the dimensions that could hold 50 standard sticks are banned under plain packaging legislation,21 however, there is no national minimum or maximum pouch size for RYO tobacco.20

In December 2023, the Australian Parliament passed a bill that will require tobacco products sold in Australia to be in standard pack sizes (also known as pack size standardisation), to be implemented in mid-2025.22 From 1 July 2025 cigarettes will only be able to be sold in packs of 20, and loose tobacco (including RYO and pipe tobacco) will only be able to be sold in pouches of 30 grams.

13.4.2.2 Unusual pack sizes

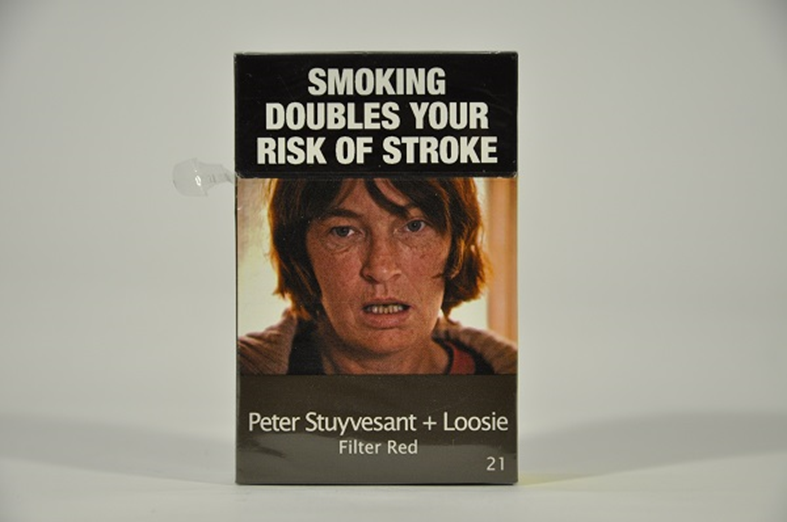

In the lead up to plain packaging in Australia and the years since its implementation, numerous non-standard FMC pack sizes such as 21s, 22s and 26s were introduced, some remaining on the market for only a short time. In 2010 there were 6 pack sizes on offer; in 2020 there were 10. These ‘odd’ packs were slightly larger than the standard Australian small packs of 20s and 25s, offering one or two more cigarettes per pack 23 —see Figure 13.4.2 below. Later, packs of 32s and 43s were introduced but remain uncommon.

Figure 13.4.2 Imperial Tobacco’s Peter Stuyvesant + Loosie 21s pack, purchased in Australia 2013

Packs of 22s or 23s also provide an intermediate price between packs of 20s and 25s. These packs have also been explicitly used by tobacco companies to absorb the impact of tax increases. In the United Kingdom, small pack sizes (providing one, two or three fewer cigarettes in the pack) were marketed after tax increases to provide products that were similarly priced to those for sale before the tax increase.24 In Australia, Dunhill 25s were repackaged as 23s in September 2016 so that the post-tax purchase price of the new 23s was the same as the price of 25s before the annual 12.5% excise increase.23 These are form of ‘shrinkflation’, where the per unit price increase is disguised by the change in product volume.2,25 Further, many products in packs of 23s are slim cigarettes that contain less tobacco per stick, such as Winfield Jets and Pall Mall Slims. These smaller cigarettes in a mid-size pack provide a further confusing price point.

A large array of pack sizes and stick dimensions makes comparing price per cigarette or gram across products very difficult for consumers26 Providing products in small sizes allows tobacco companies to preserve profits: products with a low upfront purchase cost helps people who smoke continue to afford tobacco rather than quit, and these products typically have a greater return per stick than products in a similar price segment but in a larger pack size.27

Unusual pack sizes are not limited to FM cigarettes: pouches of 27, 45 and 55 grams of RYO tobacco have also been available in addition to traditional 30, 35, 40, and 50 gram pouches, and newer smaller offerings such as 25, 15, and then 10 grams.28

13.4.2.3 Factory-made cigarette pack size range over time

Pack size offerings tend to differ by price segment in Australia (see also Table 13.3.1). The majority of brands offer 20s or 25s, often both, while brands from the budget end of the market also tended to offer large pack sizes. Figure 13.4.3 shows the number of FMC brand-pack size offerings from major manufacturers from 2001. (Note these counts exclude variant offerings—just one pack size offering per brand or sub-brand is included).

There are four apparent phases of product offerings over this period. First, between 2001 and 2006 there was little change in the market, with just under 50% of all packs containing 20 cigarettes. Next, the total market began to grow, particularly after the large 25% increase in excise duty on 1 April 2010, from about 50 offerings to more than 60 in 2011. The number of 20s packs remained steady while the number of 25s packs increased. Pack of 30s or larger remained about one-quarter of the total market until the mid-2010s.

In the third phase from 2012 to 2017 (during which time there were four annual 12.5% increases in excise duty), the total number of product offerings increased with the introduction of unusual pack sizes such as 21s, 22s, 23s and 26s. Such packs formed up to 14% of the market over this period. The number of packs of 20s remained stable, while the number of packs of 25s declined. This coincides with increased promotion of 20s over 25s on price boards in tobacco retailers.27 The number of 30s and 40s offerings gradually increased over this period.

From 2018 onwards (during which time there were four further annual 12.5% tax increases, and 3 additional annual 5% increases), the number of unusual packs decreased while the number of pack offerings in all other pack sizes—with the exception of 50s and mid-30s packs—increased. In the early 2020s, about one-third of the market was 20s, 25% were 25s, approximately 20% were 30s, and about 14% were 40s. Between 2024 and 2025, the number of packs of 20s increase from 33 to 41, likely in preparation for forthcoming pack size standardisation regulations. However, there was no corresponding decrease in pack sizes other than 20s that will be non-compliant after 1 July 2025.

Figure 13.4.3 also shows that the total number of brand-pack size combinations on the FMC market more than doubled from 2001 to 2025. The number of brand-pack size offerings increased from 64 in 2017 to 106 in 2025.

13.4.2.4 Roll-your-own tobacco pouch size range over time

Figure 13.3.4 below shows a marked change in the composition of RYO market offerings over the past two decades. Until 2008, the RYO market was mostly comprised of pouches of 50 or 55 grams, with a small number of 30-gram offerings. From 2009, pouches of 30 and 35 grams also declined, replaced by pouches of 25 grams (and one 27-gram product). Pouches of 20 grams were introduced in 2016, followed by pouches of 15 grams in 2018. These new small pouches were generally added to existing pouch size ranges—they did not replace existing products—so that the number of brand-pack size offerings was more than 50% larger in 2015 compared to 2001, and 2.5 times larger in 2019 than in 2001. This period of dramatic change in the RYO market corresponded to increasing use of RYO tobacco, particularly exclusive RYO use among females and young adults aged under 30 years.28

From 2018, the number of pouches of 40 grams of tobacco or above remained steady, although the 50-gram pouches declined in favour of new 40-gram offerings. In 2008, no pouches were less than 30 grams, whereas in 2024, more than 70% of market offerings were pouches of 25 grams or less. More than one-quarter of the RYO market was pouches of 15 grams in 2024.

As seen with FMC products, there was an increase in the number of products available in the standard pouch size of 30 grams, but not a decrease in pouches available in other pack sizes. Pouches that smaller and larger than 30 grams will not be compliant with the pack size standardisation regulations that will come into effect on 1 July 2025.

Small RYO pouches are not unique to Australia. Pouches as small as 4, 10 and 12.5g grams were available in the UK until these were banned in 2017.29 Pouches of 10 grams were observed on the Australian market in early 2022.30 The largest available pouch size (Longbeach 55 grams) was discontinued in about 2020 and replaced with a 45-gram offering.

13.4.2.5 Pack and pouch size popularity in Australia over time

Figure 13.4.5 sets out the proportion of cigarette sales that were of larger pack sizes (i.e. 30s and larger) in Australia for years for which relevant information is available. Large pack sizes substantially increased in popularity from 1985 to 1997, with more than two-thirds of all packs sold in Australia in 1997 being packs of 30s or larger. From 2006, the overall popularity of large packs decreased—although sales of packs of 40s steadily increased. Packs of 50s were half as popular in 2013 as they were in 1993, and popularity of packs of 30s and 35s also declined. Packs of 20s and 25s were no more or less popular in 2013 than they were in 2006.

Data on the sale of cigarettes by pack size are not publicly available for RYO products, or for FMC products after 2013. Examining what smokers report purchasing from surveys can serve as a proxy for this data. Figures 13.4.6 and 13.4.7 show the most popular pack sizes among adults who currently smoke from the Australian arm of the International Tobacco Control survey, for FMC and RYO packs, respectively.

Figure 13.4.6 shows a very similar distribution of pack sizes in 2013 to the sales data reported for the same year in Figure 13.3.5, although with a slightly higher proportion of 20s and 21s packs, and fewer 25s packs. There was little change in the pack size distribution in 2014, but in 2016 the proportion of 20s packs grew while the proportion of 25s shrank, but the overall proportion of packs of fewer than 30 sticks remained at almost 50%. This continued in 2018, although the proportion of packs of 30s grew. The popularity of packs of fewer than 40 sticks grew further in 2020, so that more than 75% of all packs from the ten leading brands in 2020 were packs of 30 or smaller. There were no meaningful differences in the pack size distribution of the most popular products between 2020 and 2022 By 2022, packs of 50 cigarette comprised 2.7% of market share among leading brands, compared to almost one-quarter of the total market in 1997. Note, however, that those who use larger pack sizes tend to smoke more cigarettes per day, so that this measure of consumers’ regular pack size will tend to underestimate the market share of sales in large packs and overestimate the apparent reduction in use.

Figure 13.4.7 shows the steady decline in the popularity of pouches of 50 grams (or more), from 65% of pouches from the five leading RYO brands in 2013, to 25% in 2022. Over this period, pouches of 30 grams also saw a large, rapid decline, from 24% in 2013 to no pouches among the most popular brands in 2020 or 2022. These were displaced by pouches of 25 grams (and 27-gram pouches from one brand), which represented one-third of all pouches from the leading RYO brands in 2014, to 54% in 2022. The emergence of 20-gram pouches is evident in 2016, and 15-gram pouches in 2018. The popularity of 20-gram pouches was eclipsed by 15-gram pouches, with almost one in seven (15%) users of the most popular RYO brands reporting using 15-gram pouches in 2022.

13.4.2.6 Pack and pouch size popularity among Australian teens

Very large packs—40s and 50s—have understandably never been popular among secondary school students given the much higher up-front purchase price. Figure 13.4.8 shows that use of packs of 30s steadily declined from 1996 to 2014, so that the percentage of students using large packs of 30 sticks or more declined from 51% in 1996 to 40% in 2002 (after reform to the tax system which addressed tax incentives to produce larger packs), down to less than 30% in 2014. The popularity of packs of 40s was highest in 2017 declined as packs of 30s increased in popularity from 2017 to 2022-23.

The popularity of packs of 20s among secondary school students has increased steadily over 1996 to 2022–23.31-38 About one-quarter of students reported using packs of 20s in 1999, gradually increasing to 33% in 2014, then growing to 51% in 2022-23. Until 2014, packs of 25s were the most common or almost equal most common pack size, however the popularity of these packs approximately halved in 2017. These patterns may reflect two types of price minimising behaviours among students in later years: seeking either best value per stick from larger packs of 30s or a low upfront purchase price from small packs of 20s. Packs of 25s rarely have the cheapest purchase price or best value per stick. These purchasing patterns may also reflect efforts by the tobacco industry to ensure small, low-priced products were consistently available as prices increased in the mid-2010s.27

Hill D, White V, and Effendi Y. Changes in the use of tobacco among Australian secondary students: results of the 1999 prevalence study and comparisons with earlier years. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 2002; 26(2):156–63. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12054336

White V and Hayman J. Smoking behaviours of Australian secondary school students in 2002. National Drug Strategy monograph series no. 54, Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2004. Available from: http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/publishing.nsf/content/mono54.

White V and Hayman J. Australian secondary school students’ use of alcohol in 2005. Report prepared for Drug Strategy Branch, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. National Drug Strategy monograph series no. 58, Melbourne: Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, Cancer Control Research Institute, The Cancer Council Victoria, 2006. Available from: http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/publishing.nsf/Content/mono58.

White V and Smith G. 3. Tobacco use among Australian secondary students, in Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2008. Canberra: Drug Strategy Branch Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2009. Available from: http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/Publishing.nsf/content/school08

White V and Bariola E. 3. Tobacco use among Australian secondary students in 2011, in Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2011. Canberra: Drug Strategy Branch Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2012. Available from: http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/Publishing.nsf/content/school11

White V and Williams T. Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2014. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, Cancer Council Victoria, 2016.

Guerin N and White V. ASSAD 2017 Statistics & Trends: Trends in substance use among Australian secondary school students 1996–2017, updated 3 Jul 2020. Cancer Council Victoria, 2019. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/trends-in-substance-use-among-australian-secondary-school-students-1996-2017.

Scully M, Bain E, Koh I, Wakefield M, and Durkin S. ASSAD 2022/2023: Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco and e-cigarettes., Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, 2023. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australian-secondary-school-students-use-of-tobacco-and-e-cigarettes-2022-2023?language=en.

Figure 13.4.9 below shows the popularity of RYO pouch sizes among Australian secondary school students in 2022–23. Approximately one-quarter of students who used RYO tobacco in the past week used pouches of 20 grams or less, one-quarter used 25–27-gram pouches, one-quarter used 30–35-gram pouches, and one-quarter used pouches of 40 grams or larger.

13.4.3 Price segments

The Australian FMC market traditionally featured three price segments: value, mainstream, and premium.39 Circa 2012, tobacco companies introduced new brands that were priced well below the cheapest existing products of the same size (predominantly 20s and 25s when first introduced), and priced well below the upfront purchase price of brands that otherwise offered the best value per stick (that is, much cheaper than the upfront cost of a 40s pack but offering a similar per stick price).40,41 These new products provided a distinct new price segment, termed supervalue or ultra-low price.42,43 Supervalue products are those with a lower price per stick than established value brands in the equivalent pack size when introduced to the market. The supervalue segment has also grown substantially in other countries such as New Zealand44 and the UK.43

Each of the three major tobacco company operating in Australia offers a range of brands across each of these four price segments. The range of the fourth largest company, Richland Express, is more limited and focuses more on the budget (value and super-value) end of the market. Prior to the introduction of plain packaging in Australia (see InDepth 11A, pack imagery, materials, colours, embossing and other packaging features were used to distinguish packs from each price segment and to appeal to different groups of consumers.42,45,46 Brand and variant names, and the presence of special features such as flavour capsules and varying types of filters, are the main distinguishing feature that remain post-plain packaging. Following plain packaging, these price segments are only apparent to consumers through brand name legacies and pricing differences at the point of purchase.27 In this context, the high price of premium brands is likely “a continued marker of superior quality”.47 The major impact of the introduction of supervalue brands, while maintaining the presence of premium products, is to create a highly dispersed tobacco market full of opportunities for consumers to down-trade to cheaper products in the face of price increases.2,43,48 The manipulation of tax pass-through across price segments is explored in Section 13.4.6 below.

Gendall and colleagues44 suggest that tobacco companies introduce new supervalue brands, rather than reducing the price of existing value brands, to allow consumers to avoid the negative perceptions that may be associated with long-standing budget brands. Initially, many supervalue brands introduced in Australia had names (and, for those introduced before plain packaging, packaging imagery) that conveyed value for money, such as Choice or Just Smokes (see Section 10.8.1.1). However, as the supervalue market grew, brands such as Parker & Simpson and Lambert & Butler emerged, that appear to mimic long-established premium brands such as Benson & Hedges. The BATA brand Rothmans, was ‘relaunched’ in 2014. The mid-2014 recommended retail price of Rothmans 25s was $26.1549 (among the most expensive premium brands) decreased to $16.35 (putting it in the supervalue segment) by September 2014.50

Figure 13.4.10 shows the number of FMC brand-pack size combinations available each year in Australia by price segment—note that this does not count each of the individual variant offerings within brands such as Blue, Gold, and Menthol. Until 2010, the FMC market was comprised of about 30% value brands, one-quarter mainstream brands, and premium brand offerings made up just under half of the market. Supervalue brands were introduced in 2010 with the launch of JPS; this new segment of the market rapidly grew so that supervalue offerings made up 25% of product offerings in 2017 and 43% in 2025. While the value segment has shrunk since 2014, and the number of premium offerings gradually declined from 2009 onwards, the total number of offerings on the market has increased due to the rise in the supervalue segment and expansion of sub-brands within the mainstream segment.

Distinct price-related segments have not been established within the RYO market, although brands are sold at different price points. The RYO market is comprised of some brands that also appear in the FMC market (e.g. Winfield, Holiday) and other brands unique to the RYO market.19,28 Figure 13.4.11 examines the brand-variant offerings on the RYO market in six categories: traditional RYO-only brands (those available before 2010), new RYO-only brands (those introduced after 2010), and brands with names that also appear on the FMC market in the supervalue, value, mainstream, and premium segments.

The total number of ‘traditional’ RYO brand-variant offerings has generally remained steady over time, fluctuating from 13 to 21 offerings. However, the proportion of the market made up by traditional brands has shrunk dramatically, from 79% in 2001, to 55% in 2011, to 33% in 2025. Mainstream and premium FMC brands have also featured on the RYO market over this period, with the number of premium product offerings remaining small, while mainstream offerings increased in 2006 and again in 2018.

RYO products from value FMC brand families were first introduced in 2006 and this category grew steadily to the mid-2010s before shrinking slightly. Supervalue FMC brands were first seen in the RYO market in 2012, growing to 12% of all product offerings in 2015, to 2022% in 2020 and 26% in 2025. Finally, new RYO-only brands emerged in 2018, and comprised 8% of all RYO offerings in 2025.

Figure 13.4.12 shows the average recommended retail price per 0.6 gram stick for each of the six RYO brand segments at March 2025. There was a clear price gradient from supervalue to premium brands. Traditional RYO-only brands had the highest average stick price, well above brands from the premium FMC category, and new RYO-only brands were priced similarly to the supervalue FMC brands, suggesting that the majority of brands added to the RYO market from 2012 onwards have been low-price brands.

Data on the popularity of FMC price segments among Australian secondary school students over time is presented in Figure 13.4.13. The price segment of the most popular five brands among students who currently smoked in each year is represented, with bar totals representing the total market share of those top five brands. Between 1984 and 2011, the most popular FMC brands among students were predominantly mainstream brands. The top five brands accounted for almost 80% of the cigarettes consumed by students.

From 2014, supervalue brands increased in popularity, displacing value brands, and the share of the top five brands that were mainstream greatly decreased. In 2022/2023, the top five brands were a mix of all four price segments, but only accounted for about two-thirds of the brands that secondary school students reported having most recently used.

13.4.4 Brand extensions

Brand ‘extensions’ (additional sub-brands introduced within a main brand family’s range), became a prominent feature of the Australian market in the late 2000s. Typically, these sub-brands offered a distinct product to the main brand range, for example:

- Different cigarette dimensions: slims or extra-long cigarettes

- Filter innovations: charcoal filters, recessed filters, flavour capsules

- Special tobacco blends.

These highly diverse products provide ‘premiumisation’ within mid- and lower-priced brands, and create opportunities for promotional pricing, price differentiation, and consumer targeting.17,46 (See Section 10.9 for a more detail discussion of brand extensions as a marketing strategy.) In some markets, brand extensions may exploit tax loopholes that apply lower excise rates for particular types of products, such as lower weight or lower value products.2,51 However, often these products—particularly flavoured and capsule products—are priced similarly to non-flavoured products.52

In recent years, several brands available for sale in Australia have begun offering brand extensions at a lower price point to the main range within that brand.19 This was first observed in 2016 for the premium brand Peter Stuyvesant, with Peter Stuyvesant Originals. The Originals sub-brand was manufactured in a different country (Ukraine) than the main brand range (New Zealand), and retailed for up to $6 less per pack than the main brand range.53 Similar brand extensions have been introduced across several major brands, with names such as Classic, Originals or Signature. Primarily, brand extensions create opportunities for brand switching, and create price dispersion, within a brand family. In the US, one study found that about one third of people who smoke reported switching within brands, compared to between 16% to 29% reporting switching across brands, so that almost half of all smokers switched brands to some extent.54 Between-brand switching was more common among more price sensitive groups such as young and low income, and those who already used discount brands. Within-brand switching was also common among young people, and those using premium brands, suggesting price may motivate both types of switching, but that within-brand switching was more motivated by product attributes.

13.4.4.1 Case study: Winfield brand family, 2004 to 2024

By way of example, the Winfield brand family has expanded markedly over the past 20 years. Figure 13.4.14 summarises the Winfield brand FMC and RYO offerings in terms of sub-brands, variants, and pack sizes (not included multi-buys and cartons), available in 5-year increments from 2004. For FMC products, the first sub-brand had been added by 2009, and an additional capsule sub-brand introduced in 2014. Over this ten-year period, the number of variants offered in the main brand range shrank slightly so the total number of single pack products was only marginally higher in 2014 compared to 2004. This variant rationalisation continued to 2019, while many more sub-brands were introduced: slim cigarettes (Jets 23s), larger sticks (Max 32s), pack size extensions to 30s and 40s, and the introduction of the budget extension Winfield Originals, priced approximately 10% lower than the main Winfield brand range in the same pack size. The range of sub-brands continued to grow to 2024, so that all Winfield FMC products were identified as sub-brands. Pricing also varied widely across sub-brands: Winfield Supreme Smooth 25s had an RRP of $48.65, compared to $63.75 for Winfield Flow Filter 25s. Despite containing less tobacco per stick, the slim sub-brand Jets 23s were more expensive per stick than Winfield Original 20s and 25s.

Note, though, this table does not fully capture the extent of ‘churn’ within the Winfield brand family. Short-lived brand FMC extensions and variants available between 2014 and 2019 include Optimum Crush Summer Rush, Optimum Wild Mist, Winfield Explorer Outback Country and Coast, and expansion of the main brand range up to packs of 50s.55

13.4.5 Alternative tobacco products: Cigarette and RYO pricing differences in Australia

The availability and pricing of tobacco products that provide an alternative to cigarettes can greatly influence the effectiveness of a tobacco excise system. In Australia, as with many Western counties, the most common factory-made cigarette alternative is roll-your-own tobacco. RYO tobacco is cheaper to manufacture than factory-made cigarettes, and so an inherent price difference exists. However, this can be exacerbated by tax structures, as seen across many European countries.56 Tobacco companies may exploit differential tax rates across types of tobacco, for example, in the US, many companies relabelled roll-your-own tobacco products as pipe tobacco following an increase in taxes on RYO.4 Alternatively, tobacco companies may over- or under-shift tobacco taxes on one type of tobacco relative to another to manipulate these price differences.57 Consumers may also increase these price differences per stick by rolling cigarettes using less tobacco per stick than a typical factory-made cigarette. Evidence from Australian RYO smokers suggested that the average weight of tobacco used per stick declined from 2006 to 2016 to about 0.5 grams;58 further research suggests that the average tobacco weight continued to decline since 2016 to about 0.4 grams in 2020.19 Rolling of low-weight cigarettes is facilitated by the broad range of small diameter filters available on the market, helpfully labelled as ‘super slim’, ‘micro’ or ‘nano’.53

In Australia, RYO tobacco had long been essentially taxed at a much lowr rate than that which applied to FM cigarettes, so that the tax on a roll-your-own cigarette was the same per stick as that for a FM cigarette only if it was rolled with 0.8 grams of tobacco. Because most RYO users roll less than 0.8 grams of tobacco per cigarette, using as little as 0.5 grams per cigarette,58 RYO tobacco provided a cheaper alternative to factory-made cigarettes (attracting less excise per cigarette). Further, as more budget brands and smaller pouch sizes have entered the RYO market in recent years (see also Figure 13.4.4 and Section 10.9), the up-front cost and price per cigarette of RYO products have provided a reliably cheaper alternative to FM cigarettes.

As described in Section 13.6.3.7, two series of adjustments to RYO excise have been introduced to reduce the discrepancy in per stick excise on RYO and FMC products. The first reduced the excise equivalisation weight from 0.8 grams to 0.7 grams over four years from 2017 to 2020, and the second will reduce the equivalisation weight from 0.7 grams to 0.6 grams from 2023 to 2027. The impact of these adjustments—and the changes in size offerings outlined in Section 13.4.2.4—on the cheapest available pack and pouch sizes is shown in Figure 13.4.15. The gap in the upfront price (recommended retail price) of the cheapest FMC and RYO packs has closed over the 2010s. This began before the RYO harmonisation policy first commenced in 2017, with the introduction of pouches of 25 grams in 2010 and 20 grams in 2016. As of 2018, the cheapest available RYO pouch was very similar in price to the cheapest FMC pack of 20 cigarettes, however, a 15-gram pouch would yield 5 more cigarettes per pack if rolled with 0.6 grams of tobacco each, or 10 more cigarettes per pack if rolled with 0.5 grams. In contrast, in 2001, the cheapest pouch of RYO tobacco cost almost double the price of the cheapest FM cigarettes. While the cheapest RYO pouch in 2001—a 30-gram pouch—would have yielded many more cigarettes than the pack of 20 cigarettes, the upfront cost to the consumer was substantially more. In 2025, the price of the cheapest RYO pouch—of 15 grams—was $5 higher than the cheapest pack of 20 FMC cigarettes.

Figure 13.4.16 shows the cheapest FMC stick price compared to the cheapest RYO stick price (at 0.6 grams of tobacco per stick). Until 2017, the gap in FMC and RYO stick prices widened. The cheapest RYO stick was approximately 72% of the cost of the cheapest FMC stick in 2001, the dispersion between these prices widened to 57% in 2017. The impact of the 2017 to 2020 RYO harmonisation policy is evident, where the gap in FMC and RYO pricing shrank to 83% in 2021. However, a budget-conscious person who smoked could still afford approximately five cigarettes for the price of four RYO cigarettes rolled with 0.6 grams—more if 0.5 grams of tobacco were used. The second RYO harmonisation policy commenced in 2023, further shrinking the gap in FMC and RYO pricing, so that the cheapest RYO stick (at 0.6 grams) was 88% of the cost of the cheapest FMC stick.

These patterns of FMC and RYO pricing are consistent with findings from Australian and UK research. A study examining self-reported prices paid for FMC and RYO products in Australia from 2007 to 2020. Cho and colleagues19 found the gap in prices paid per stick between FMC and RYO cigarettes decreased from 24% in 2018 to 9% in 2020, but that the reported prices paid price for a typical 0.7 gram stick remained lower than the average FMC stick. A RYO-targeted tax policy was introduced in 2017 in the UK, in which a Minimum Excise Tax (MET) was applied to FMCs and a tax increase targeted to RYO products occurred. A study examining tobacco prices from 2015 to 2018 found that the MET was successful in increasing budget FMC prices and reducing dispersion within the FMC market itself, but the targeted taxes did not reduce dispersion between FMC and RYO products.

13.4.6 Strategic tax pass through of tobacco tax increases

Increases in tobacco taxes are only effective if they are passed on to the consumer as intended.59 Pre-announced tax increases allow tobacco companies to develop complex tax pass-through strategies across their product ranges. Tobacco companies can blunt the impact of tax increases by manipulating how much of the tax increase is passed on to different products, and the timing of these increases.

13.4.6.1 Under and over-shifting

The practice of under and over-shifting tobacco taxes involves tobacco companies and/or retailers changing tobacco prices by a different amount than what would be expected by the change in tax. This may be in the form of under-shifting, where the price of tobacco products increases less than would be expected by the tax increase; over-shifting involves increases prices by more than necessary. In the case of under-shifting tobacco companies absorb the portion of the excise increase that is not passed on to consumers.60 By minimising the impact of the price increase, consumption may not fall as much as would be expected if the tax increase was passed on in full, so profits do not necessarily decrease.4,61 Over-shifting increases profit margins, but the timing of these increases means that consumers attribute the entire price increase to the tax increase, not to the tobacco company producing the product.62

Under- and over-shifting have been frequently observed in numerous countries. In an international systematic review of studies examining under and over-shifting,3 over-shifting was observed in 17 of 22 studies in high income countries, and under shifting was observed in 12 studies, with both occurring in 9 of these studies. In eight of the studies in which differential tax pass-through was observed, over-shifting was the predominant pattern. In contrast, in low- and middle-income countries, under-shifting was more common. Across 15 studies, under-shifting was observed in 14 studies and over-shifting in six. In the five studies which observed both under and over-shifting, under-shifting was the predominant pattern in three.3 A 2023 study of tax pass through patterns in 12 sub-Saharan African countries found a mix or predominant over or under-shifting, or a combination of both, across these countries.63

Importantly, under- and over-shifting may occur in tandem across a company’s range of products, referred to as differential pass through. These selective price changes ensure that price dispersion grows, cheap products are available (or appear available) to encourage down-trading, and more profitable products continue to remain on the market for those less sensitive to price. Several patterns of differential pass through may occur:

- Under-shifting budget brands while fully passing the tax increase on to higher-priced brands.24,64

- Over-shifting across all products, but greater over-shifting among more expensive products.65,66

- Under-shifting budget brands while over-shifting other products, keeping the price of budget products artificially low.43,57,67,68

- Under-shifting of budget brands following implementation of other tobacco control policies, such as plain packaging.44

- Selectively over-shifting more on particular products to manipulate the price differences between factory-made and roll-your-own products,57,69 or particular types of cigarettes such as flavour capsules.70

- Geographic patterns of differential tax pass-through, such as greater over-shifting in more socio-economically advantaged areas compared to more deprived areas.66

13.4.6.2 Evidence of over-shifting in Australia

Evidence of differential pass-through of tobacco taxes can be examined by comparing the change in the tax and non-tax components of tobacco prices over time. The non-tax component of the price excludes excise and goods and services tax (GST), leaving the production and distribution costs and profits. Large and/or consistent increases in the non-tax share above the tax rate indicate purposeful over-shifting.

Figure 13.4.17 shows the average change in the tax and non-tax price of leading FMC and RYO products from 2018 to 2024. The advertised retail price of FMC products was 181% higher overall in 2024 compared to 2018, but the non-tax component increased by a substantially higher proportion than the excise rate: 206% compared to 169%. The same pattern was seen for leading RYO products: overall, the price of RYO products was 201% higher, due to the excise being 195% higher and the non-tax share being 221% higher in 2024 than 2018.

Figures 13.4.18 and 13.4.19 explore the increase in the tax and non-tax share of FMC and RYO prices further, respectively. The shaded portions of each graph represent years in which there were no real increases (i.e. above indexation) in tobacco excise. Figure 13.4.18 shows the excise rate and the average non-tax share of FMC products by price segment from 2018 to 2024. The differences in pricing strategies by price segment are clearly evident, with the non-tax share of advertised price being $0.58 lower per stick for supervalue compared to premium products in 2024. In 2024 the excise rate was 169% higher than in 2018, whereas the non-tax value of the price of tobacco products was 206% higher overall. Value products showed the largest increase, at 237% higher in 2024 compared to 2018, followed by mainstream (212% higher, and supervalue and premium products (each 200% higher).

Figure 13.4.19 shows a very similar pattern for RYO products. Traditional and mainstream RYO brands showed higher non-tax value components than budget and more recently introduced (new) brands, and the spread in prices across segments has grown over time. For RYO products, the non-tax value of the price increased between 2020 and 2022 in the traditional and mainstream but not the supervalue, budget, and new segments. The non-tax value share of RYO products was 221% higher than 2018 on average, with greatest increases in the supervalue segment (254% higher). Value brands were the only category where the non-tax share increased by a smaller margin than the excise rate (133% higher).

13.4.6.3 Cushioning or price smoothing

Tobacco companies and retailers can also minimise the impact of tax increases on consumers by raising prices incrementally, rather than in one large change.2 Consumers are protected from the intended impact of a large price increase (i.e. a large tax increase); they may be less likely to be aware the of the full extent of the price increase if it is spread across several months. Often, price increases have been observed across several months after a tax increase, however tobacco companies may also pre-emptively begin to raise prices, increasing their revenue for the months before the excise increases. This practice can also manipulate evaluations of the success of a tax increase (or another tobacco control policy): if prices rise before the tax increase (or implementation of the measure) and consumption correspondingly declines, there would be not demonstrable impact on consumption when the tax increase or other policy measure is actually implemented.4

Price smoothing has been observed in the UK,3,57 the US,4 Mexico,70 and Australia.71 In Australia, the prices of FCM and RYO products in large supermarkets were observed to increase in the months after routine indexation of tobacco excise, and a large annual increase in tobacco excise, even after a large increase in prices in the month of the annual excise increase.71 In the UK, Partos and colleagues57 observed under-shifting in the months after a tax increase, then smoothing the price increase across the remainder of the year. They observed of this price manipulation in years with large sudden tax increases (2010 to 2012), compared to years with smaller, pre-announced increases (2013 to2015).

13.4.7 Discounting strategies

Tobacco manufacturers set recommended retail prices for tobacco products, updated at least twice-yearly when excise rates are adjusted. However, the final sale price of tobacco products may vary considerably from the recommended rate. Discounting can occur at several levels:

- Temporary price specials for specific products in particular retailers

- Discounting across retailer types and/or area level characteristics

- Bulk-buy discounts for multi-pack bundles such as cartons and twin packs

- Discounts offered to specific consumers through coupons or targeted price promotions2 (not permitted in Australia)

- Pricing differentials can also occur across jurisdictions, encouraging cross-border shopping;72 this issue tends to occur across countries with shared land borders or within-country jurisdictions with different tax systems such as US reservations.73

While small, independent retailers such as proprietors of local corner stores, and convenience retailers including petrol stations, typically sell cigarettes at the recommended prices, the majority of cigarettes in Australia are sold at considerably lower prices from major retail outlets such as supermarkets and tobacconists.74 As well as selling single packets of cigarettes at well below the recommended prices, these retailers also sell cigarettes in multi-pack bundles such as twin packs and cartons at a discounted rate. Therefore, these discounting strategies may be additive. Price discounts allow price-sensitive consumers to source cheaper tobacco products, encourage consumers to purchase more tobacco than intended, attract new consumers, and, where price discounts vary over time, retail type, and locations, confuse price signals intended by excise increases. The apparent transient nature of price specials can prompt impulsive spending based on emotion rather than rational decision making.17 Price discounts are so effective in stimulating sales studies have repeatedly shown price discounts dominate the marketing expenditure of tobacco companies.75,76 In 2019, 87% of tobacco marketing expenditure in the US was spent on price discounts.76

13.4.7.1 Temporary price discounts

In its 1994 report on the cigarette industry, the Prices Surveillance Authority noted various common forms of discounting, including lower prices for stock bought in high volumes, and the phenomenon of 'specialling' where manufacturers encourage high-volume retailers (especially tobacconists and supermarkets) to discount one or two of that company's brands for a week or longer periods.77 These price specials can also occur in the form of ‘buy-downs’, where the price of a product is reduced and the supplier funds the discount that is experienced by consumers.78

These price specials are typically highlighted on at the point of sale, listed on price boards or verbally communicated by the retailer.78 Because of the temporary nature of price specials, they are difficult to quantify in terms of their duration, size of discount, and the type of products most frequently discounted. One retail audit in Melbourne, Australia, found that in 2015, 15% of the top-listed items on tobacco price boards at the point of sale were marked as discounted, i.e. ‘specials’, a non-significant increase from 9.3% in 2013.27 Price specials, and other price display strategies such as left-digit pricing, where a price is set just below an even dollar amount (i.e. $19.99 instead of $20.00) may be used to keep displayed tobacco prices below psychologically important price thresholds.27,79,80

13.4.7.2 Area and retail-based discounted pricing

Prices for the same tobacco products can differ across retailers, based on retailer type or other area-based characteristics such as socioeconomic disadvantage. Numerous retail audit studies in major Australian cities have consistently shown greater price discounting in supermarkets and tobacconists compared to stores such as convenience retailers, petrol stations, small independent stores (e.g. newsagents), and alcohol licensed venues.74,81,82 Other studies have shown greater discounting in stores within low SES areas,82,83 areas with a higher proportion of the population under 18 years of age.82 An 2013 study in the state of Queensland found a greater density of tobacco retailers, and that tobacco was sold in a greater variety of store types, in low socioeconomic areas. They found an overall tendency for tobacco products to be cheaper in lower socioeconomic areas, however, this area-based difference did not hold within store types.84

A 2019 study from the US found that the price of the cheapest cigarette pack available in ‘dollar stores’ (highly discounted outlets) was lower than all other store types other than tobacconists.85 Further, these stores were more likely to be located in rural areas and areas with lower median income, a higher proportion of young people. In contrast, a 2018 study examining expenditure on tobacco products in convenience stores across neighbourhoods in Scotland found no difference in tobacco prices for the same products across areas, however overall spending was lower in more socioeconomically deprived areas, reflecting greater sales of cheaper brands.86 This study examined only one store type, with the authors noting price often varies by retailer type, and area-level variations in price may also vary by store type.86

13.4.7.3 Bulk-buy discounts

At least traditionally, larger pack sizes offer better value per stick than smaller packs. It is cheaper to produce one pack of 40 cigarettes than two packs of 20 sticks, and this is reflected in pricing. Across several Australian studies, cartons and twin packs have shown to offer discounts relative to single packs of the same brand and single pack size of 14%,74 10%,42 or 7%.17 However, volume discounts are also available for twin-pack and carton purchases, with multipack purchases noted to be particularly effective in increasing sales, above discounts on single packs.17

Volume-based discounting can encourage greater purchasing through several mechanisms.17 Due to past experiences with greater volume discounts for large products, consumers can become conditioned to make large purchases. Also, the anchoring effect may influence pack size purchasing decisions, where consumers try to assess the ‘normal’ amount of tobacco that other consumers purchase.17 The availability of a variety of very large pack sizes may lead consumers to assume large purchases are normal.

An examination of the characteristics people who purchased cartons from the Australian arm of the International Tobacco Control Study19 showed that people who purchased cartons were more likely to smoke daily, be more heavily addicted, and more likely to have intentions to quit smoking. People who purchased cartons were more likely to be from the highest income group, and rates of carton purchase were lower in 2016 to 2020 compared to 2007–08, perhaps reflecting the very high upfront cost of bulk purchases in later years.

Related reading

Relevant news and research

A comprehensive compilation of news items and research published on this topic

Read more on this topic

Test your knowledge

References

1. Chaloupka FJ, IV, Peck R, Tauras JA, Xu X, and Yurekli A. Cigarette excise taxation: the impact of tax structure on prices, revenues, and cigarette smoking. NBER Working paper No. 16287 Cambridge, Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w16287.

2. STOP. The Price We Pay: Six Industry Pricing Strategies That Undermine Life-Saving Tobacco Taxes. A Global Tobacco Industry Watchdog, 2023. Available from: https://exposetobacco.org/resource/tobacco-taxes/.

3. Sheikh ZD, Branston JR, and Gilmore AB. Tobacco industry pricing strategies in response to excise tax policies: a systematic review. Tob Control, 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34373285

4. Ross H, Tesche J, and Vellios N. Undermining government tax policies: Common legal strategies employed by the tobacco industry in response to tobacco tax increases. Prev Med, 2017. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28625418

5. Pesko MF, Xu X, Tynan MA, Gerzoff RB, Malarcher AM, et al. Per-pack price reductions available from different cigarette purchasing strategies: United States, 2009-2010. Prev Med, 2014; 63:13-9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24594102

6. Licht AS, Hyland AJ, O’Connor RJ, Chaloupka FJ, Borland R, et al. How Do Price Minimizing Behaviors Impact Smoking Cessation? Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2011; 8(5):1671-91. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/8/5/1671

7. Choi SE. Are lower income smokers more price sensitive?: the evidence from Korean cigarette tax increases. Tobacco Control, 2016; 25(2):141-6. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/25/2/141.abstract

8. Licht AS, Hyland AJ, O’Connor RJ, Chaloupka FJ, Borland R, et al. Socio-economic variation in price minimizing behaviors: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) four country survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2011; 8(1):234–52. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/8/1/234/pdf

9. Geboers C, Nagelhout GE, de Vries H, Candel M, Driezen P, et al. Price minimizing behaviours by smokers in Europe (2006-20): evidence from the International Tobacco Control Project. Eur J Public Health, 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36215655

10. Choi K, Kreuger K, McNeel TS, and Osgood N. Point-of-sale cigarette pricing strategies and young adult smokers' intention to purchase cigarettes: an online experiment. Tob Control, 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33632805

11. Organization WH. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2015: raising taxes on tobacco. World Health Organization, 2015. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/178574/1/9789240694606_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1.

12. Partos TR, Gilmore AB, Hitchman SC, Hiscock R, Branston JR, et al. Availability and use of cheap tobacco in the UK 2002 - 2014: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Project. Nicotine Tob Res, 2017. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28525594

13. Lopez-Nicolas A and Branston JR. Promoting convergence and closing gaps: a blueprint for the revision of the European Union Tobacco Tax Directive. Tob Control, 2021; 24 May tobaccocontrol-2021-056496. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34031225

14. Hill D, White V, and Scollo M. Smoking behaviours of Australian adults in 1995: trends and concerns. Med J Aust, 1998; 168:209-13. Available from: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/1998/168/5/smoking-behaviours-australian-adults-1995-trends-and-concerns

15. Blackwell AKM, Lee I, Scollo M, Wakefield M, Munafo MR, et al. Should cigarette pack sizes be capped? Addiction, 2020; 115(5):802-9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31376200

16. Blackwell AKM, Lee I, Scollo M, Wakefield M, Munafo MR, et al. Size matters but when, why and for whom? Addiction, 2020; 115(5):815-6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32056316

17. Greenland SJ, Gill R, Moss S, and Low D. Marketing unhealthy brands – an analysis of SKU pricing, pack size and promotion strategies that increase harmful product consumption. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 2023:1-16. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0965254X.2023.2176532

18. Persoskie A, Donaldson EA, and Ryant C. How tobacco companies have used package quantity for consumer targeting. Tobacco Control, 2018. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/tobaccocontrol/early/2018/05/31/tobaccocontrol-2017-053993.full.pdf

19. Cho A, Scollo M, Chan G, Driezen P, Hyland A, et al. Tobacco purchasing in Australia during regular tax increases: findings from the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project. Tob Control, 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37652676

20. Hanley-Jones S, Wood L, Letcher T, and Winstanley M. 5.13 Products and packaging created to appeal to new users, in Tobacco in Australia: Facts & issues. Greenhalgh E, Scollo M, and Winstanley M, Editors. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2022. Available from: https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-5-uptake/5-13-products-and-packaging-created-to-appeal-to-n.

21. Tobacco Plain Packaging Regulations 2011 2011. Available from: http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2011L02644/Download.

22. Public Health (Tobacco and Other Products) Bill 2023 [Provisions] and Public Health (Tobacco and Other Products) (Consequential Amendments and Transitional Provisions) Bill 2023 [Provisions] [November 2023] (Cth). Available from: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Tabled_Documents/4236.

23. Scollo M, Occleston J, Bayly M, Lindorff K, and Wakefield M. Tobacco product developments coinciding with the implementation of plain packaging in Australia. Tob Control, 2014. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24789601

24. Hiscock R, Branston JR, McNeill A, Hitchman SC, Partos TR, et al. Tobacco industry strategies undermine government tax policy: evidence from commercial data. Tobacco Control, 2018. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/tobaccocontrol/early/2018/03/24/tobaccocontrol-2017-053891.full.pdf

25. Collier K. Packets of cigarettes to shrink. Herald Sun, 2016.

26. Moodie C, Hoek J, Scheffels J, Gallopel-Morvan K, and Lindorff K. Plain packaging: legislative differences in Australia, France, the UK, New Zealand and Norway, and options for strengthening regulations. Tobacco Control, 2018. Available from: https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/tobaccocontrol/early/2018/08/01/tobaccocontrol-2018-054483.full.pdf

27. Bayly M, Scollo M, White S, Lindorff K, and Wakefield M. Tobacco price boards as a promotional strategy—a longitudinal observational study in Australian retailers. Tobacco Control, 2018; 27(4):427-33. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/tobaccocontrol/27/4/427.full.pdf

28. Bayly M, Scollo MM, and Wakefield MA. Who uses rollies? Trends in product offerings, price and use of roll-your-own tobacco in Australia. Tob Control, 2019; 28(3):317-24. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30030409

29. Opazo Breton M, Britton J, and Bogdanovica I. Changes in roll-your-own tobacco and cigarette sales volume and prices before, during and after plain packaging legislation in the UK. Tob Control, 2020; 29(3):263-8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31073097

30. Scollo M and Bayly M. 10.7 Market share and brand share in Australia, in Tobacco in Australia: Facts & issues. Greenhalgh E, Scollo M, and Winstanley M, Editors. Melbourne: Cancer Council Victoria; 2020. Available from: https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-10-tobacco-industry/10-7-market-share-and-brand-share-in-australia.

31. Hill D, White V, and Effendi Y. Changes in the use of tobacco among Australian secondary students: results of the 1999 prevalence study and comparisons with earlier years. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 2002; 26(2):156–63. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12054336

32. White V and Hayman J. Smoking behaviours of Australian secondary school students in 2002. National Drug Strategy monograph series no. 54, Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2004. Available from: http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/publishing.nsf/content/mono54.

33. White V and Hayman J. Australian secondary school students’ use of alcohol in 2005. Report prepared for Drug Strategy Branch, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. National Drug Strategy monograph series no. 58, Melbourne: Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, Cancer Control Research Institute, The Cancer Council Victoria, 2006. Available from: http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/publishing.nsf/Content/mono58.

34. White V and Smith G. 3. Tobacco use among Australian secondary students, in Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2008. Canberra: Drug Strategy Branch Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2009. Available from: http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/Publishing.nsf/content/school08

35. White V and Bariola E. 3. Tobacco use among Australian secondary students in 2011, in Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2011. Canberra: Drug Strategy Branch Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2012. Available from: http://www.nationaldrugstrategy.gov.au/internet/drugstrategy/Publishing.nsf/content/school11

36. White V and Williams T. Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco, alcohol, and over-the-counter and illicit substances in 2014. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, Cancer Council Victoria, 2016.

37. Guerin N and White V. ASSAD 2017 Statistics & Trends: Trends in substance use among Australian secondary school students 1996–2017, updated 3 Jul 2020. Cancer Council Victoria, 2019. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/trends-in-substance-use-among-australian-secondary-school-students-1996-2017.

38. Scully M, Bain E, Koh I, Wakefield M, and Durkin S. ASSAD 2022/2023: Australian secondary school students’ use of tobacco and e-cigarettes., Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, 2023. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australian-secondary-school-students-use-of-tobacco-and-e-cigarettes-2022-2023?language=en.

39. Carter SM. The Australian cigarette brand as product, person, and symbol. Tobacco Control, 2003; 12 Suppl 3:iii79–86. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/12/suppl_3/iii79.full.pdf

40. Scollo M, Bayly M, and Wakefield M. Did the recommended retail price of tobacco products fall in Australia following the implementation of plain packaging? Tobacco Control, 2015; 24:ii90-ii3. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/24/Suppl_2/ii90.full

41. Scollo M, Zacher M, Coomber K, Bayly M, and Wakefield M. Changes in use of types of tobacco products by pack sizes and price segments, prices paid and consumption following the introduction of plain packaging in Australia Tobacco Control, 2015; 24:ii66-ii75. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/24/Suppl_2/ii66.full

42. Greenland SJ, Johnson L, and Seifi S. Tobacco manufacturer brand strategy following plain packaging in Australia: implications for social responsibility and policy. Social Responsibility Journal, 2016; 12(2):321-34. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-09-2015-0127

43. Gilmore AB, Tavakoly B, Taylor G, and Reed H. Understanding tobacco industry pricing strategy and whether it undermines tobacco tax policy: the example of the UK cigarette market. Addiction, 2013; 108(7):1317-26. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/add.12159/abstract;jsessionid=64E2E87AD5AF72AC84107081697F45AA.d02t03

44. Gendall P, Gendall K, Branston JR, Edwards R, Wilson N, et al. Going 'Super Value' in New Zealand: cigarette pricing strategies during a period of sustained annual excise tax increases. Tob Control, 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/36008127

45. Greenland SJ. The Australian experience following plain packaging: the impact on tobacco branding. Addiction, 2016. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27557863

46. Greenland SJ. Cigarette brand variant portfolio strategy and the use of colour in a darkening market. Tobacco Control, 2013. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2013/08/29/tobaccocontrol-2013-051055.abstract

47. Critchlow N, Moodie C, Best C, and Stead M. Anticipated responses to a hypothetical minimum price for cigarettes and roll-your-own tobacco: an online cross-sectional survey with cigarette smokers and ex-smokers in the UK. BMJ Open, 2021; 11(3):e042724. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33753438

48. Gendall P, Hoek J, Branston J, Edwards R, and Wilson N. How can we address tobacco companies’ manipulation of cigarette prices?, in Public Health Expert2022. Available from: https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/pubhealthexpert/how-can-we-address-tobacco-companies-manipulation-of-cigarette-prices/.

49. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Price lists-cigarettes. The Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2014; 91(April-May-June edition).

50. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Price lists-cigarettes. The Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2014; 92(July-August-September edition).

51. Krishnamoorthy Y, Majella MG, and Murali S. Impact of tobacco industry pricing and marketing strategy on brand choice, loyalty and cessation in global south countries: a systematic review. Int J Public Health, 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32712692

52. Rajani NB, Qi D, Chang K, Kyriakos CN, and Filippidis FT. Price differences between capsule, menthol non-capsule and unflavoured cigarettes in 65 countries in 2018. Prev Med Rep, 2023; 34:102252. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37252069

53. Scollo M, Bayly M, White S, Lindorff K, and Wakefield M. Tobacco product developments in the Australian market in the 4 years following plain packaging. Tobacco Control, 2018; 27:580-4. Available from: https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/27/5/580

54. Cornelius ME, Cummings KM, Fong GT, Hyland A, Driezen P, et al. The prevalence of brand switching among adult smokers in the USA, 2006–2011: findings from the ITC US surveys. Tobacco Control, 2015; 24(6):609-15. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/24/6/609.abstract

55. NSW Retail Tobacco Traders' Association. Price lists-cigarettes. The Australian Retail Tobacconist, 2018; 105(Jan- Feb - Mar):5-6.

56. Nicolás A. How important are tobacco prices in the propensity to start and quit smoking? An analysis of smoking histories from the Spanish National Health Survey. Health Economics, 2002; 11(6):521–35. Available from: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/98016568/abstract

57. Partos TR, Hiscock R, Gilmore AB, Branston JR, Hitchman S, et al. Impact of Tobacco Tax Increases and Industry Pricing on Smoking Behaviours and Inequalities: A Mixed-Methods Study, in Impact of tobacco tax increases and industry pricing on smoking behaviours and inequalities: a mixed-methods study. Southampton (UK): 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32271515.

58. Branston JR, McNeill A, Gilmore AB, Hiscock R, and Partos TR. Keeping smoking affordable in higher tax environments via smoking thinner roll-your-own cigarettes: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey 2006-15. Drug Alcohol Depend, 2018; 193:110-6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30352334

59. World Health Organization. WHO technical manual on tobacco tax policy and administration. Geneva: WHO, 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240019188.

60. Apollonio DE and Glantz S. Tobacco manufacturer lobbying to undercut minimum price laws: an analysis of internal industry documents. Tob Control, 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31969381

61. Nargis N, Hussain A, Goodchild M, Quah ACK, and Fong GT. Tobacco industry pricing undermines tobacco tax policy: A tale from Bangladesh. Prev Med, 2020:105991. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31954145

62. McKenzie P. NZ tobacco companies use tax hikes as cover in Newsroom2019. Available from: https://www.newsroom.co.nz/2019/11/21/913218/nz-tobacco-using-tax-increases-as-cover#.

63. Sheikh ZD, Branston JR, van der Zee K, and Gilmore AB. How has the tobacco industry passed tax changes through to consumers in 12 sub-Saharan African countries? Tob Control, 2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/37567600

64. van Schalkwyk MCI, McKee M, Been JV, Millett C, and Filippidis FT. Analysis of tobacco industry pricing strategies in 23 European Union countries using commercial pricing data. Tobacco Control, 2019. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31028176

65. Wilson LB, Pryce R, Hiscock R, Angus C, Brennan A, et al. Quantile regression of tobacco tax pass-through in the UK 2013-2019. How have manufacturers passed through tax changes for different tobacco products? Tob Control, 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33093189

66. Wilson LB, Angus C, Brennan A, Gillespie D, Shortt NK, et al. Quantile regression of tobacco tax pass-through in the UK 2017-2021: how have manufacturers passed through tax changes for different tobacco products in small retailers? Analysis at the national level and by neighbourhood of deprivation. Tob Control, 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39848682

67. Marsh L, Cameron C, Quigg R, Hoek J, Doscher C, et al. The impact of an increase in excise tax on the retail price of tobacco in New Zealand. Tobacco Control, 2016; 25(4):458-63. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/25/4/458.abstract

68. Berthet Valdois J, Van Walbeek C, Ross H, Soondram H, Jugurnath B, et al. Tobacco industry tactics in response to cigarette excise tax increases in Mauritius. Tobacco Control, 2019. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31685585

69. Hiscock R, Augustin NH, Branston JR, and Gilmore AB. Standardised packaging, minimum excise tax, and RYO focussed tax rise implications for UK tobacco pricing. PLoS One, 2020; 15(2):e0228069. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32053603

70. Saenz-de-Miera B, Welding K, Tseng TY, Grilo G, and Cohen JE. Tobacco industry pricing strategies during recent tax adjustments in Mexico: evidence from sales data. Tob Control, 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39107105

71. Bayly M, Scollo M, and Wakefield MA. Evidence of cushioning of tobacco tax increases in large retailers in Australia. Tobacco Control, 2021. Available from: https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/early/2021/07/25/tobaccocontrol-2020-056385

72. Agaku IT, Blecher E, Filippidis FT, Omaduvie UT, Vozikis A, et al. Impact of cigarette price differences across the entire European Union on cross-border purchase of tobacco products among adult cigarette smokers. Tobacco Control, 2016; 25(3):333-40. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/25/3/333.abstract

73. Kelton M and Givel M. Public policy implications of tobacco industry smuggling through Native American reservations into Canada. International Journal of Health Services, 2008; 38(3):471–87. Available from: http://baywood.metapress.com/app/account/shopping-cart.asp?eferrer=offerings&action=purchase&backto=contribution,1,1;issue,6,11;journal,1,151;linkingpublicationresults,1:300313,1&id=1358686

74. Scollo M, Owen T, and Boulter J. Price discounting of cigarettes during the National Tobacco Campaign, in Australia's National Tobacco Campaign: evaluation report vol. 2. Hassard K, Editor Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care; 2000. p 155-200 Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.195.8891&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

75. Ma H, Reimold AE, and Ribisl KM. Trends in Cigarette Marketing Expenditures, 1975-2019: An Analysis of Federal Trade Commission Cigarette Reports. Nicotine Tob Res, 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34988582

76. Levy DT, Liber AC, Cadham C, Sanchez-Romero LM, Hyland A, et al. Follow the money: a closer look at US tobacco industry marketing expenditures. Tob Control, 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/35074930

77. Prices Surveillance Authority. Report no. 52: inquiry into cigarettes declaration. Matter no: PI/94/1. Melbourne, Australia: PSA, 1994.

78. Watts C, Burton S, and Freeman B. 'The last line of marketing': Covert tobacco marketing tactics as revealed by former tobacco industry employees. Glob Public Health, 2020:1-14. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32946326

79. Dewhirst T. Price and tobacco marketing strategy: lessons from 'dark' markets and implications for the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Tobacco Control, 2012; 21(6):519–23.

80. Hayes L. Smokers' responses to the 2010 increase to tobacco excise; findings from the 2009 and 2010 Victorian Smoking and Health Surveys. Melbourne, Australia: Centre for Behavioural Research in Cancer, Cancer Council Victoria, 2011.

81. Scollo M, Bayly M, and Wakefield M. The advertised price of cigarette packs in retail outlets across Australia before and after the implementation of plain packaging: a repeated measures observational study. Tobacco Control, 2015; 24:ii82-ii9. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/24/Suppl_2/ii82.full